Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the July 14, 2013 Newsletter issued from the Frio Canyon Nature Education Center in the valley of the Dry Frio River in northern Uvalde County, southwestern Texas, on the southern border of the Edwards Plateau; elevation ~1750m (~5750 ft); N29.62°, W99.86°; USA

BLACK WILLOW

Except on main highways, instead of bridges, here we have "low-water crossings," which means that roads simply dip into and out of normally dry streambeds -- arroyos, as they're called here -- or else cross on modest culverts with drainpipes through them. Sometimes water pools behind culverts creating communities of marsh and aquatic plants. Beside such a culvert a couple miles south of here a willow leans toward the road, a willowy branch of which is shown above.

That picture shows that nowadays the lower parts of young branches on mature female willows of this species bear capsule-type fruits. Some of the capsules already are splitting open, releasing seed-bearing fuzz into the wind, as shown below:

The seeds are so small that you might not notice them. Below, you can see one embedded in fuzz in the picture's top, right corner:

In most of eastern North America the most commonly encountered willow is the Black Willow, SALIX NIGRA, whose flowers and leaves we've admired at http://www.backyardnature.net/n/w/blackwil.htm.

However, the online Flora of North America describes 113 willow species for North America -- mainly occurring in northern states and provinces, and in the western mountains -- out of about 450 worldwide, so, which species is this? Despite looking just like Black Willows I've known back East, I had high hopes that our southwest Texas tree might be something new for me. You can see its leaves and slender, yellow-brown stem below:

Despite our edge-of-desert location, our roadside tree turns out to be another Black Willow. In fact, Black Willows extend well into Mexico, so you just have to admire this species' vigor and adaptiveness.

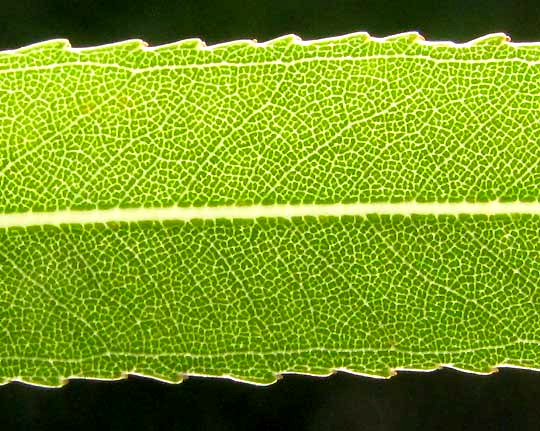

Field marks distinguishing Black Willows from other willow species include the long, narrow shape of the leaves and, especially, the fact that leaf undersurfaces are nearly the same color as leaf tops. Leaf undersurfaces of many willow species are noticeably paler than the tops. Speaking of the leaves, behold the elegant arabesques displayed by a willow leaf held against the sun:

from the March16, 2009 Newsletter, issued from the forest near Natchez, Mississippi; elevation ~400ft (120m), ~N31.47°, ~W91.29°:

BLACK WILLOWS FLOWERING

The refuge's most abundantly flowering tree species was certainly the Black Willow, SALIX NIGRA. In waterlogged soils Black Willow formed pure stands and the trees were loaded with flowers. Since willows come in male and female trees (they're "dioecious") we always knew which sex we were passing by, for the flower clusters look very different.

Above you see a male tree's yellow, finger-length catkins composed of many male flowers consisting of clusters of pollen-producing stamens.

Above female catkins show up as greener, more compact items consisting of many packed-together pistils. The flattish, whitish things atop each pistil are stigmas -- the place where pollen grains are supposed to land and germinate. Pistils consist of stigma, style and ovary, and mature into fruits, which in the willows' case are dry capsules.

Five willow species are listed for Mississippi. Flowering Black Willows are distinguished by each male flower having three to five stamens instead of one or two, which is more common in the genus. Also, Black Willow's male flowers occur in whorls along the slender inflorescence axis instead of spirally (you can see the whorls in the above picture of male flowers, especially on the pale catkin in the lower left). Black Willow's leaves also are dark green on both sides, instead of having much paler undersurfaces, which many willow species have.

Maybe one reason large parts of the Refuge are occupied with very dense Black Willow thickets is that almost all willows take root from broken branches that fall onto the ground, and Black Willow stems are somewhat brittle. When I was a tree-planting kid on the farm in Kentucky my father warned me many times not to plant willows around the house because their roots grew far from the tree and formed masses of interlacing roots wherever they found water, as in our water well, plus they could enter water pipes not perfectly sealed and clog them. In Nature the willows' dense root networks protect stream banks from erosion.

from the June 2, 2002 Newsletter, issued from near Natchez, Mississippi:

BLACK WILLOW FUZZ

The green, too-low water in the Gate Pond was strewn all across with cottony fuzz. The fuzz-curdles atop the water consisted of an abundance of white- parachuted seeds fallen from Black Willows all around the pond's edges. As I spied on the bathing birds, fingernail-sized starlets of white, sun-glowing fuzz constantly drifted across my binoculars' field of vision. Willow fuzz flew just everywhere.

Of course, only the female willows were releasing fuzz. Black Willows, SALIX NIGRA, come in male trees and female trees, as do all the members of the Willow Family, which includes over a hundred willow species in North America, as well as the poplars and cottonwoods.