BACKYARD NATURE HOME

| NATURALIST NEWSLETTER HOME | WHO WE AREPLANTS | ANIMALS | ECOLOGY | GEOLOGY | GARDENING | TOOLS

BACKYARD NATURE HOME

| NATURALIST NEWSLETTER HOME | WHO WE AREExcerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the June 27, 2010 Newsletter issued from Hacienda Chichen Resort beside Chichén Itzá Ruins, central Yucatán, MÉXICO

ANTLION FLOOR

The traditional Maya thatch-roofed hut I live in has a dirt floor, which I like. I enjoy how it feels beneath my bare feet and how you don't have to worry about tracking dirt in from the outside. Even before I moved in I knew it'd be hard to keep my feet presentable, especially the toenails, which nowadays stay pretty much black and disreputable looking.

Antlion removed from pit. Picture taken during earlier stay in southwestern Mississippi

Antlion removed from pit. Picture taken during earlier stay in southwestern MississippiAntlion larvae excavate conical pits all across the hut's dry dirt floor. A small invertebrate falls into the pit and the larva hidden in the dirt below the pit has a meal. You can see some pits beside my vine door at the top of this page.

Pits like that stretch all across my floor. I can't walk without smashing them, and I'm sorry about that, but it's just one of those things.

By the way, notice the ingenious manner by which the fellows set the pole around which the vine door swings atop a mostly buried, upside-down bottle with a concave bottom. That's not "traditional Maya," but it's traditional the way the Maya use whatever they have to very good effect.

from the June 27, 2010 Newsletter issued from Hacienda Chichen Resort beside Chichén Itzá Ruins, central Yucatán, MÉXICO

ANTLION EXPERIMENTS

A couple of Newsletters ago I wrote about Doodlebugs, or Antlions. In response I got a letter from Ellen and Cori McGuirk, ages 10 and 7-1/2, in Nashville, Tennessee, offering some of their own observations.

Ellen writes: "What it does is it has to snap several times before it can really get the ant. And the ant can pull itself up sometimes by the little bits of sand or gravel. Usually it falls back down but sometimes it manages to get back up. If the antlion does catch it, then it slowly pulls it back into its pit. If there's lots of ants, for example sixteen, then the antlion doesn't even bother to catch it."

Cory adds: "Once I got an ant and I put it in an antlion's hole and then I put an antlion beside the ant and it didn't do anything."

Then Ellen: "Also if you leave them down beside the ant then they don't bother to catch it, they don't even try. (Beside the ant, not in a pit.)"

These are such fine observations, and they are exactly right, and very thought provoking. What I especially like is their observation that if you put an ant and an antlion side-by-side, not in the usual way with the antlion beneath the sand pit, the antlion won't do anything.

This reminds me of some classic insect-behavior experiments by the great French naturalist J. Henri Fabre. Fabre noticed that wasps pulled their preys into their nests by the preys' antennae. He snipped off the antennae, and the wasps couldn't figure out to grab hold of any other parts of the preys' bodies. Fabre decided that his wasps had been born with the instinct to tug on their preys' antennae, but that they couldn't really think out what they were doing. There's more to this story at my Web page on insect behavior at www.backyardnature.net/bugbhav.htm.

Nowadays most who study the matter might say that antlions never "know" what they do at all. Many would say that insects are like small computers hardwired for a few specific tasks. Something happens that stimulates a response, and one thing automatically leads to another. Antlion larvae are "programmed" by the DNA in their genes to find dry dirt or sand deep enough for a pit, to dig a pit, to bury themselves in the sand beneath the pit, to clamp their jaws on whatever tumbles into the pit, and to suck the victim dry. If anything happens outside that scenario, the antlion isn't equipped mentally to deal with it. It's like when a computer freezes and you have to "hot boot it" -- turn it off and on -- and then it just sits there no wiser than ever, waiting for a command it can recognize.

Cory and Ellen have done some sophisticated experiments, and their observations were sharp and accurate. Hearing from folks like these is very encouraging.

from the July 6, 2014 Newsletter issued from the Frio Canyon Nature Education Center in the valley of the Dry Frio River in northern Uvalde County, southwestern Texas, on the southern border of the Edwards Plateau; elevation ~1750m (~5750 ft); N29.62°, W99.86°; USA

ADULT ANTLION

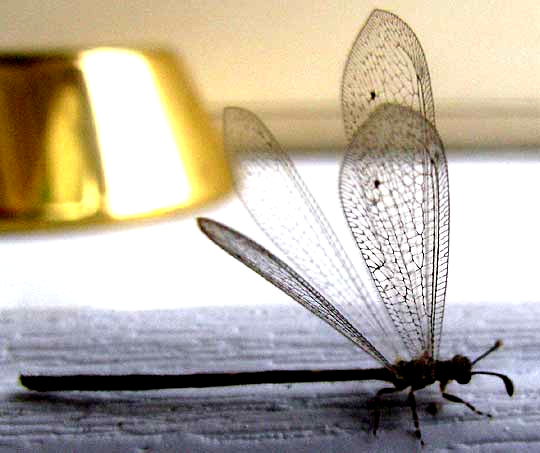

Antlions are larvae of a specific kind of insect. Insect larvae are what emerge from eggs of kinds of insects that undergo complete metamorphosis

(egg/larva/pupa/adult). Though antlion pits often are abundant in dry places, few of us know what antlion adults look like. This week one turned up on my neighbor Phred's garage

-- looking like a damselfly with a moth's antennae. That's it at the right.

Antlions are larvae of a specific kind of insect. Insect larvae are what emerge from eggs of kinds of insects that undergo complete metamorphosis

(egg/larva/pupa/adult). Though antlion pits often are abundant in dry places, few of us know what antlion adults look like. This week one turned up on my neighbor Phred's garage

-- looking like a damselfly with a moth's antennae. That's it at the right.

Notice that very unlike the larva this adult bears no pincer-like mandibles. The BugInfo.Com website tells us that " The adult antlion feeds on a variety of foods, such as nectar, pollen, or even other small insects, depending on the species of antlion" but the online Antlion page of the Encyclopaedia Britannica says that "Since the adult does not feed, the larva must consume sufficient food to sustain the adult." Whatever the case, with such small mouthparts adults certainly can't prey on small invertebrates the way they did during their larval stage.

When I pulled the camera in closer for a better look at the adult's head and antennae, the critter suddenly unfurled its two sets of wings, enabling the shot shown below:

Adult antlions normally are nocturnal, and this one had been attracted to Phred's security lamp. Along with other night-fliers, mostly moths, he was found there at dawn, probably exhausted from a night of trying to navigate by the light as if it were a far-away star, but succeeding only in going in exhausting circles.

from the February 21, 2016 Newsletter issued from Hacienda Chichen Resort beside Chichén Itzá Ruins, central Yucatán, MÉXICO

DOODLEBUG DOODLING

When I was a kid on the farm in Kentucky my father told me that the pits were dug by doodlebugs that were buried just beneath the pit's bottom, its pincers open, ready to nab any ant or other such small critter who might tumble into the pit. He showed me how to stick a grass stem into the hole and sometimes draw it out with an antlion hanging on its tip. However, he taught me that antions are called doodlebugs. I've always assumed that the name doodlebug was a local name not known outside the region but this week I learned otherwise when I was researching the wandering line leading to or from an antlion pit in the Hacienda's garden, shown below:

Looking for an explanation for the squiggling line on Wikipedia's Antlion Page, I read, "The antlion larva is often called "doodlebug" in North America because of the odd winding, spiraling trails it leaves in the sand while looking for a good location to build its trap, as these trails look as if someone has doodled in the sand."

So, the term doodlebug isn't just a rural, western Kentucky invention, and at least the Wikipedia author thinks that the trails are made by larvae looking for a good place to dig their pits. That may or may not be the whole explanation, but at least for right now it firms up my intention to keep calling antlion larvae doodlebugs.