Nearly a century ago, in his own backyard, the famous French naturalist J. Henri Fabre witnessed a little drama in which the participants were a wasp, a bee, and a mantis. The wasp was a sphecid (family Sphecidae), and sphecids are predatory. At the right you see a predatory wasp carrying a stung caterpillar to her nest, to feed her young.

Nearly a century ago, in his own backyard, the famous French naturalist J. Henri Fabre witnessed a little drama in which the participants were a wasp, a bee, and a mantis. The wasp was a sphecid (family Sphecidae), and sphecids are predatory. At the right you see a predatory wasp carrying a stung caterpillar to her nest, to feed her young.

The wasp Fabre was watching was licking nectar from a captured honeybee's tongue. But the little drama didn't stop there. Suddenly the predatory wasp fell victim to an even larger and more aggressive insect predator, a true Tyrannosaurus rex of the insect world, a Praying Mantis. That's a mantis at the left.  Grasping the wasp with its saw-like front legs, the mantis immediately set about munching the wasp's belly.

Grasping the wasp with its saw-like front legs, the mantis immediately set about munching the wasp's belly.

But, the story doesn't even stop here. Now the seasoned naturalist Fabre saw something that even he referred to as "an awful detail": As the mantis devoured the wasp rear-end first, the wasp's front part never ceased licking the bee's tongue...

What does it all mean? Here's at least one train of thought:

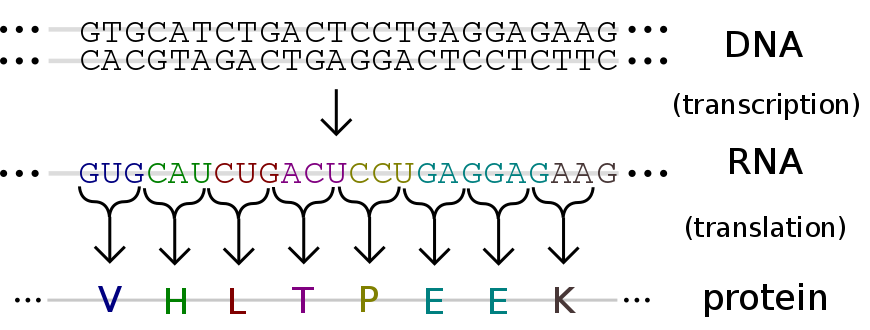

Having those thoughts bouncing around in our heads, now let's consider the generally accepted notion that insects behave strictly according to instinct; Their behavioral patterns are "programmed" in their genes; It's innate. It's quite as if insects were beautifully complex little machines controlled by computers more advanced than we humans yet have manufactured.

The insect experiences a stimulus, such as sensing that a bee's crop is filled with nectar, and its automatic response is to squeeze the bee in a certain way and lick the bee's tongue. There's nothing personal, nothing evil or sneaky about the behavior. The behavior is just what results from the genetic code formulated during the evolution of the wasp's ancestors.

To further make his point, Fabre describes another of his classic experiments. A certain wasp species always drags its demobilized victims to the nest by tugging on the prey's antennae. When Fabre snipped off the preys' antennae, the wasp couldn't figure out to grab another part of the prey's body -- a mouthpart or front leg, for instance. The wasp was programmed to pull its paralyzed prey by its antennae, and it simply didn't have the intelligence to do anything other than what its genetically encoded instinct instructed it to do.

But, again, even here the story doesn't end. For, nowadays, on the fringes of the field of insect behavior, some are at least considering the possibility that at least a few of the most recently evolved kinds of insects, especially communal ones such as bees and ants, may sometimes behave in ways not entirely "programmed by their genes."

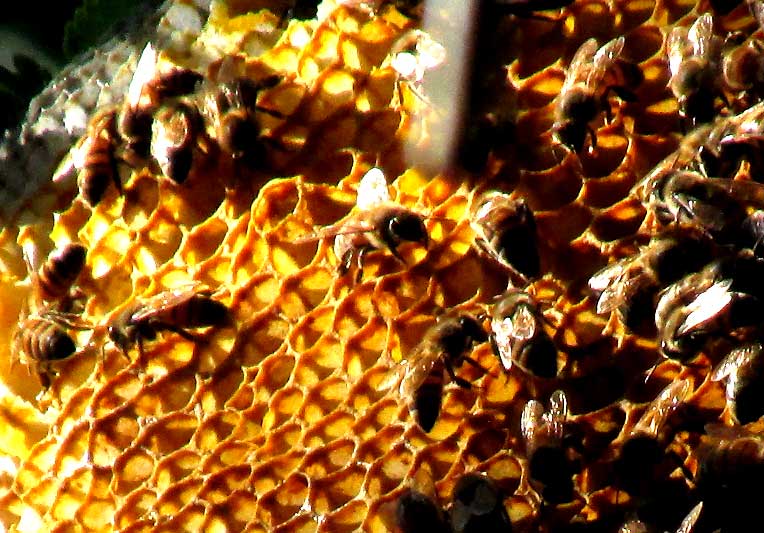

Bees have been found to "recognize human faces." More specifically, they can pick out individual features on human faces and recognize those features during repeat interactions. Apparently they can understand the concepts of "same" and "different," even differences in shapes and colors. They seem to understand the concept of zero, because when trained to fly to images of fewer dots or symbols -- choosing, say, three dots instead of five -- they tend to favor a blank image, or "zero" over an image with a single dot.

If you want to see what the latest research reveals about this matter, on the Internet search on the keywords "insect metacognition."

But, the story doesn't stop here...

For, even farther onto the fringes of the science of animal behavior there's growing interest in ideas such as neuroscientist Giulio Tononi's "integrated information theory." One of many thoughts entangled with that theory is that among honey bees possibly the main seat of consciousness is not within the individual bee, but in the hive. The individual bee may be analogous to a red blood cell in a human body. Who says that a consciousness must be maintained by blood flowing in a circulatory system, and not flying through the air on glistening wings?

To see just how far thoughts can go when they begin by noticing what happens with a wasp, a bee and a mantis in one's own backyard, you may enjoy browsing the somewhat technical discussion on Wikipedia's Integrated Information Theory Page.