Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

entry dated April 6, 2023, with notes from the lower slope of hill south of El Cerrito, 5kms south of Tequisquiapan; bedrock volcanic andesite, an intermediate rock between basalt and rhyolite; elevation about 2,000m (6600 ft), Querétaro state, MÉXICO

(~N20.47°, ~W99.89°)

TIGHT ROCKSHIELD LICHEN

On the grossly overgrazed, eroded lower slope of the ridge south of El Cerrito, the above foliose lichen was common on the abundant rocks of igneous origin lying atop the ground, the soil having eroded from around them. Besides its being a foliose lichen on a rock, other important field marks for identification include: its chalky whiteness; its flattish thallus lobes growing right on the rock surface, not loosely, and; the presence of numerous dark-centered, bowl-shaped, spore-producing apothecia of various sizes clustering mostly toward the lichen's center.

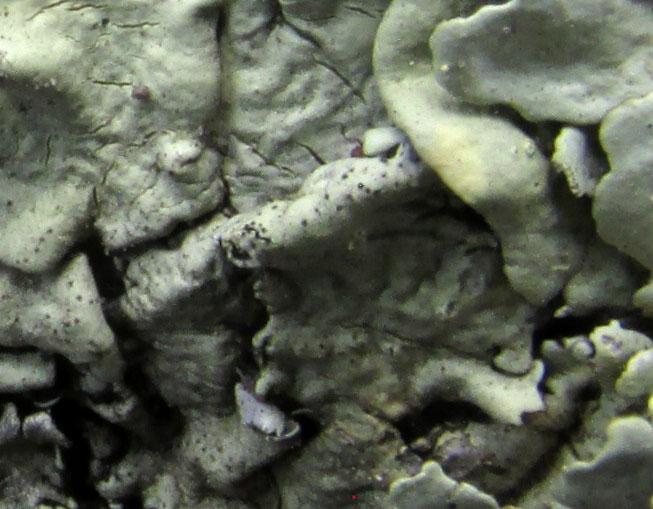

Up close, the outer lobes themselves bear lobes, and grow outward from the lichen's center in a bifurcating manner, their tips dividing into new forking lobes. Notice at the image's lower, right, on older parts of the thallus, the white surface is speckled with tiny, black dots. Here's a close-up of the dotting on thallus surfaces closer to the lichen's center:

And here the dots extend into the lichen's center area where cup-shaped apothecia cluster:

The dots are pycnidia, which typically are tiny openings in the thallus surface, beneath which opens a larger, hollowed-out, somewhat teardrop-shaped space. Inside the hollow grow hairlike, fungal hyphae at the tips of which spores called pycnidiospores, are asexually produced. The spores escape into the air through the hole above the hollow.

So, pycnidia are one way the lichen reproduces asexually, and many lichen kinds don't have them. Their presence, arrangement and density are good field marks. It's the same with the bowl-shaped apothecia, except that spores produced by the apothecia are sexual in nature, involving the mixing of genes from two fungus strains. Spores are released from the dark area inside the cups. In this species the apothecias' size and the way they cluster so densely in the center is noteworthy. Most of our lichen's apothecia are smallish, but a few larger ones exist, though they're mostly deformed or collapsed. Sometimes small apothecia grow on the stems of larger ones.

In some parts of the world field guides are available for lichen identification, but not in Mexico. Still, my former experience with lichens and the Internet sometimes enables an identification. Here was my approach with this species:

On our Newsletter Lichen Index page, you can see that we've identified numerous foliose lichen species. For example, we've already met the Common Greenshield Lichen, conspicuous on branches of mesquite trees around our rock-growing one, and fairly similar in appearance to it -- white, leafy thalli expanding outward from the body center, their outer lobes unattached to the substrate. From experience I know that foliose lichens generally structured like that typically belong to the family Parmeliaceae. That's a big family with over 2700 species in about 71 genera, occurring worldwide in many habitats and climatic conditions, so it's a good family -- and often easy -- to recognize.

Assuming we had a member of the Parmeliaceae, on the GBIF Parmeliaceae page, in the map showing the worldwide occurrence of documented collections of this family, I centered on central Mexico and "zoomed in" until only a few yellow occurrence dots were visible here in Querétaro state, and then clicked on "Explore area." This loaded a page listing the names of all members of the family documented in this area.

Several genera were mentioned. I did image searches on each genus until a picture resulted of a very similar, or identical, species to ours. That picture belonged to a member of the genus Xanthoparmelia, whose species often are known as rockshield lichens. With about 724 species, Xanthoparmelia is the largest genus of all foliose lichens. It's been described as the dominant genus of the world's foliose, rock-inhabiting lichens in hot, semi-arid climates.

Then I went through the same process, this time starting with the GBIF Xanthoparmelia page. Once I zoomed in on Xanthoparmelia species in Querétaro state and hit "Explore area," I was presented with a surprising number of species, so I did image searches on each one. The best match -- identical it seemed to me -- was with XANTHOPARMELIA LINEOLA, often referred to as the Tight Rockshield Lichen. My guess is that the "tight" arises from its thalli holding so snugly onto the rock surface, instead of growing loosely.

The LichenPortal.Org Xanthoparmelia lineola page describes the species as very common at intermediate to lower elevations throughout the Sonoran Desert of the southwestern US and northwestern Mexico, growing on acidic rocks, and volcanic rocks are generally acidic. Seeing that it's been well documented in our area, our ID has a fairly high chance of being correct. However, the taxonomy of this widespread and variable species isn't well understood, and it's always iffy to ID by pictures.

In the 2022 study by Joshua Anthuan Bautista-González and others entitled "Traditional knowledge of medicinal mushrooms and lichens of Yuman peoples in Northern Mexico," our lichen is reported as used to relieve urinary tract ailments in general. At least one person used the lichen as a decoction for treating cancer. Another used Xanthoparmelia species to treat stomach pain and empacho, a stomach discomfort caused by eating too much, eating spoiled or unwanted food, or feeling embarrassed or disgusted while eating.

In Spanish such rock-growing lichens often are called flor de piedra, meaning stone-flower, or sometimes hongo de piedra, stone-mushroom, and other such names.