Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

entry from field notes dated May 6, 2023, on small gravel road descending into valley east of Curva de la Doctorcilla, which is on the road connecting Hwy120 and El Doctor; oak, pine and juniper forest on limestone bedrock; elevation ±2650m (8700 ft); Eastern Sierra Madre mountains of east-central Querétaro state, MÉXICO, (N20.88°, W99.62°)

ARBUTUS MOLLIS

On the steep slope of an old roadcut the above bush deserved attention because at the tips of its branches flowers were beginning to open:

The whitish corollas, somewhat egg shaped and narrowing at the top to a small opening -- "urceolate" in shape -- immediately evoked the Heath Family, the Ericaceae. This surprised me, for nearly always I've found members of this family in acidic soils, but here we were on limestone, which produces calcareous, basic soils.

Above, another surprise seen up close was that the plant's vegetated parts were heavily invested with gland-tipped hairs, including the flowers' calyxes and pedicels.

If you snip off the top of a corolla, you see what's shown above. Surrounding the glistening green stigma are ten pollen-producing, raspberry-colored anthers, each anther consisting of two bag-like compartments split open, enabling pollen to escape. The flowers tend to hang downward within their inflorescences, so pollen would fall through these slits. Each anther part bears a hair-like appendage, which many assume helps shake pollen through the slits, perhaps a bee's buzz causing the spur to vibrate, shaking pollen loose. Here's a side view of the stamens:

The stamens' long-hairy filaments enlarge greatly toward the base but are very narrow at their tops, a design making it easier for the anthers to shake out their pollen.

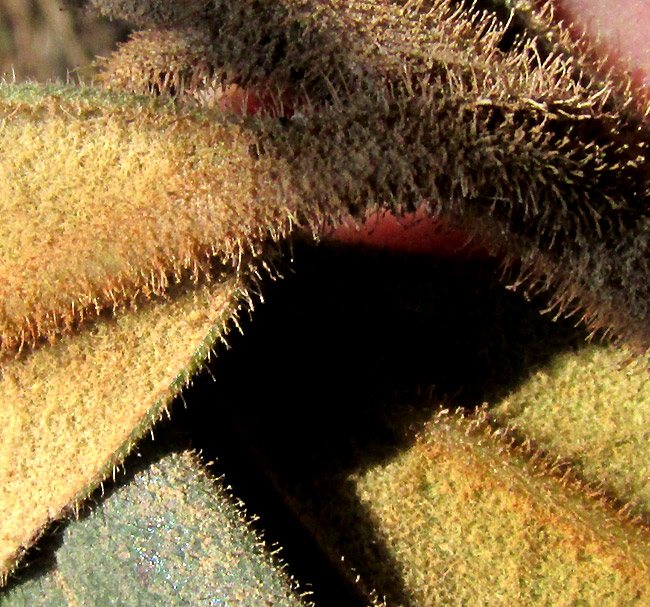

Above you see the extent of the glandular-hairiness of a stem (top right in the picture), a lower leaf surface (left side of picture and lower right), and upper leaf surface (silvery blade in bottom left corner). Lower leaf surface are so heavily covered with slightly rusty-colored hairs that the leaf surface below the hairs is invisible. The leaves are bicolored, silvery above and rusty-silvery below. Hairs average about 1mm long.

In this part of upland central Mexico known as the Bajío Region, if you have a woody member of the Heath Family no more than leg tall, but flowering with the corollas arising above their ovaries (superior ovaries), and the bush's leaf undersurfaces are so hairy that the blades' surfaces can't be seen, with the hairs averaging about 1-1.5mm long, you have ARBUTUS MOLLIS.

In North America, species of Arbutus are known as madrone trees, and noted for their smooth, reddish bark which exfoliates in flakes, as seen at the bottom of our Pacific Madrone page. However, Arbutus mollis is a bush with no red, exfoliating trunk and usually no more than 1.2m tall (4ft), so it doesn't fit the madrone mold.

Arbutus mollis is endemic just to Mexico, occurring in oak/pine and fir forests from the uplands of Durango state and northeastern Mexico south to Oaxaca.

In the 2014 volume of the Flora del Bajío treating the Heath Family, only one population of Arbutus mollis is documented in Querétaro state, and it's not in this area. Moreover, the Flora says of that population that it "... dilutes into a hybrid swarm with Arbutus xalapensis" -- "se diluye en un enjambre híbrido. -- the species Arbutus xalapensis being more commonly found in this area. Finally, it remarks that Arbutus mollis hybridizes with Arbutus tessellata, and that species occurs in this area.

In the Flora, our plant "keys out" to the "glandular variant" of Arbutus mollis, which is distinguished from the "glandular variant" of Arbutus xalapensis not only by being a flowering, low bush and not a tree, but also by its leaf undersurfaces being so densely covered with hairs that the blade's surface can't be seen.

I suppose that the Flora refers to a "glandular variant" instead of as a variety with glandular hairs because no formal naming of such a variety of plants looking like ours has been published. Yet it's clear that populations with glandular hairs certainly exist, though the Flora del Bajío documents none from Querétaro state.

My impression is that our plant belongs to a group of intergrading, hybridizing taxa that haven't been studied enough to know what's going on with them. These designations such as "glandular variant of Arbutus mollis" should be seen as place-holders waiting for clarification.

In that light, I'm glad to offer the above information for whomever that student willing to accept the challenge turns out to be.

Entry from field notes dated June 30, 2023, from along narrow, very steep, cobblestone road descending on the south side of El Doctor, passing among cultivated fields and pastures; in the mountains of east-central Querétaro state, municipality of Cadereyta de Montes, 12 straight-line kms due east of Vizarrón de Montes but much farther by twisting roads; elevation ~2740m (~8900 ft), Querétaro, MÉXICO, (N20.84704°, W99.58573°)

YOUNG FRUIT FORMING

Now later in the season, the bush's young, berry-type fruits are forming, shown above. Note how the berry's surface is covered with tiny bumps, and that the flower's style and stigma remain. Technically, berries are defined as fleshy fruits with a stone or pit produced from a single flower producing one ovary. Strawberry and blackberry fruits are not, technically, berries, but rather multiple fruits consisting of tiny individual fruits grown together.