LICHEN STRUCTURE

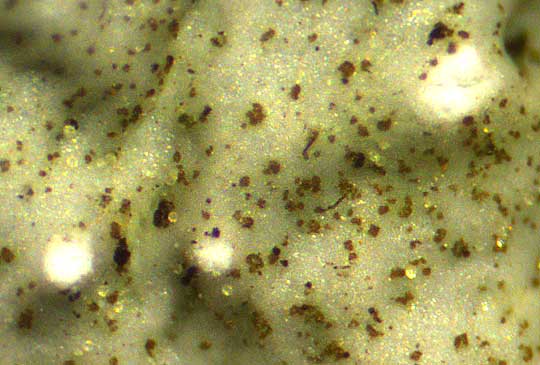

Lichens are not plants. They are composite organisms composed of cells of photosynthesizing algae and/or cyanobacteria held together by cobwebby filaments of various species of fungus. Also, they're "jam-packed full of bacteria," as lichen researcher Toby Spribille says. Within lichens some bacteria provide defense, while others make vitamins and hormones. The above sketch gives a general idea of how threadlike fungal hyphae wrap around algal cells. The photomicrograph below shows how it really is.

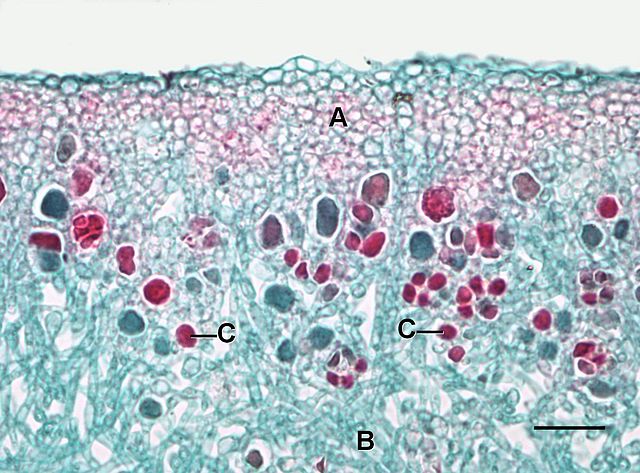

Photomicrograph of cells in Umbilicaria lichen; A=Fungal layer (upper cortex), B=Medulla (algal cells), C=Algal cells; scale bar=0.02mm; image courtesy of Jon Houseman, via Wikimedia Commons

Photomicrograph of cells in Umbilicaria lichen; A=Fungal layer (upper cortex), B=Medulla (algal cells), C=Algal cells; scale bar=0.02mm; image courtesy of Jon Houseman, via Wikimedia CommonsDespite the lichen's amazing structure and lack of recognition by the general public, they're abundant and important for the maintenance of the planetary biosphere.

In Merlin Sheldrake's much-read Entangled Life (Random House, 2020), we read that lichens encrust as much as 8% of the Earth's surface, which is more than that covered by tropical rainforests.

At the right, in the pretty Golden-eye Lichen, as with other lichen species, the fungal part of the body provides form to the lichen and enables reproduction. The golden-topped, umbrella-like features are apothecia, which are fungal in nature, and release fungal spores.

When a spore is released and finds a new home, if environmental conditions are good for germination, and if the appropriate species of algae or cyanobacteria are nearby, a new Golden-eye Lichen may form. In exchange for the fungus's gifts of form and sexual reproduction, the algal and/or cyanobacteria cells photosynthesize food for the whole lichen body. It's a classic symbiotic relationship -- two or more different organisms in a mutually beneficial relationship.

KINDS OF LICHEN:

Lichenologist Walter Fertig at Arizona State University's Lichen Herbarium tells us that possibly 17-30% of all fungus species are capable of becoming lichens. Since it's believed that the number of fungus species may be over 1.5 million, there may be at least 250,000 lichen species. Above and at the left, that's one of those species, the Wolf Moss, which is a lichen despite its name.

Traditionally, the vast realm of lichen species has been divided into the three broad categories listed at the left, where the links lead to examples and information about each type. Nowadays other forms also are recognized -- such as the Fishscale Lichen, regarded as a squamulose type -- but for our backyard needs, these three provide a good starting point.

Both the Golden-eye and the Wolf Moss seen above are fruticose lichens, as their branching, bushy form suggests. The Calcareous Rimmed Lichen at the right, looking like a crust, is a crustose type.

LICHEN ECOLOGY:

Ecologically, lichens often occupy niches which, at least sometime during the season, are so dry, or hot, or sterile, that little else will grow there. At the left, maybe three crustose species grow on a Mesquite tree twig in hot, semi-arid southwestern Texas. The main species, with cracks forming blocks bearing dark dots in their centers, is the Pore Lichen. But the ecological challenge for each species is the same. Just imagine how most of the time very little water and nutrients are available on that twig.

An even more hostile environment is that of naked rock exposed to intense dryness, temperature extremes and sunlight, such as is shown at the right. There the Black Pit Lichen somehow thrives on a sun-blasted, wind-lashed, exposed limestone rock also in very hot, semi-arid southwestern Texas.

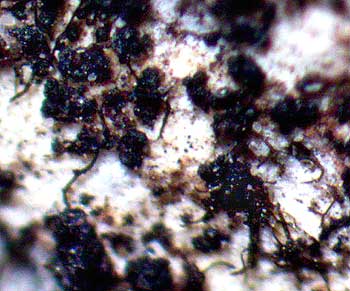

Though water and wind erosion deform rocks and sometimes pit them, the above Black Pit Lichen contributes to the pit-making by secreting acids that dissolve the cement holding together the rock on which it grows. At the left, a much magnified image shows the Black Pit Lichen's thallus separated into individual warty bodies, which issue root-like appendages atop the naked rock. The pitting produced by this lichen surely has taken centuries to occur.

If a lichen species survives where other forms of life are unable to, then that species has evolved special adaptations. For example, many fruticose lichens, like the Powdery Twig Lichen at the right, not only are much branched but also the branches branch, and those branches branch again. By increasing surface area exposed to air, these branches absorb water from the air when it's foggy or when dew covers things in early morning.

Crustose lichens on bare rock often begin a succession of communities, as described on one of our ecology pages. When your foot dislodges a patch of lichen from a rock, you may be undoing the patient work of centuries.

Certain lichens, like the unidentified ones at the left, live on leaves, sometimes as parasites. These special leaf-living lichens are known as foliicolous lichens (not foliose).

Despite lichens having evolved over millions of years to occupy many habitats, they are very vulnerable to pollution, as seen in the picture below:

The roof's dark part is produced by lichens. The clear part lacks lichens. Possibly air pollution from the chimney caused the lichen-free zone below the chimney, though more likely mineral leakage from the metal chimney caused the lichens to die. Often "zinc strips" and galvanized flashing on roofs are marketed for their ability to "... effectively kill or retard the growth of mosses and fungi and appear to have effect up to 15 feet below the zinc flashing along the length of the flashing," as one ad for zinc flashing says.

LICHEN REPRODUCTION:

Lichens reproduce in two ways: sexually and asexually.

Sexual reproduction is handled by the lichen's fungal part. The great majority of lichen species belong to the fungus phylum Ascomycota, in which spores are produced in bowl-like apothecia such as the ones at the right, of the Eastern Speckled Shield Lichen. If the spores land in a suitable environment in which to germinate, and if the fungal hyphae encounter the right species of alga and/or cyanobacteria, the hyphae will grow around the cells and a new lichen will begin developing. These are big IFS, with the consequence that many lichen species reproduce much more asexually than they do sexually.

Asexual, or vegetative, reproduction, therefore, is so important to lichens that among the various species it's accomplished in various ways.

- FRAGMENTATION: In this very common and very simple method, parts of the lichen body break off, and those parts then form new lichen bodies. Squamules are plate-like items, often overlapping. At the right, the Firedot Lichen produces button-like, spore-producing apothecia surrounded by flaky squamules. When you step on a squamulose lichen it shatters, and each broken-off and scattered squamule is eligible for becoming a new lichen.

- ISIDIA, & SORALIA WITH SOREDIA: At the right, the Powdered Ruffle Lichen bears grainy-looking, soredia-producing soralia along its thallus margins. Isidia are like very tiny warts on the lichen thallus. They're composed of both fungal and algal cells, so when an isidium breaks off, it can form a new lichen. Soredia also are packages of both fungal and algal cells, except that soredia cluster in tiny, open-topped soralia, or are scattered across the lichen thallus. The difference between soredia and isidia is that wartlike isidia are covered with a kind of "skin," while isidia lack such a covering.

- PYCNIDIA WITH CONIDIA: Pycnidia are closed, flask-like structures often visible as tiny black dots in the lichen thallus. At the right you see some in a close-up of the thallus of an Eastern Speckled Shield Lichen. Pycnidia contain lots of conidia. Conidia are basically asexual fungal spores NOT accompanied by cells of alga or cyanobacteria. Therefore, like a lichen's sexual spores, to form a new lichen, conidia somehow escaped from the lichen thallus and land close to the right species of photosynthesis-performing alga or cyanobacteria cells.

The technical literature mentions yet other kinds of asexual lichen reproduction, but they're hard to identify in the field and often there's debate about how they function. For example, there's schizidia, phyllidia, folioles and blastidia, and who knows what else?

MORE INFORMATION:

On the Web, check out these sites:

LichenPortal.Org

Lichens of North America

Wikipedia's Lichen Page

Wikipedia's Lichens of the United States

Wikipedia's Lichens of Europe page

Jim's field notes on lichens