Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the February 10, 2013 Newsletter issued from the valley of the Dry Frio River in northern Uvalde County, southwestern Texas, on the southern border of the Edwards Plateau; elevation ~1750m (~5750 ft); N29.62°, W99.86°; USA

CALCAREOUS RIMMED LICHEN

Atop sun-baked, windswept, limestone hills framing the valley of the little Dry Frio River flowing behind the cabin, the vegetation becomes sparse -- just a few grasses, cacti and small, spiny shrubs. Atop the hard, Cretaceous-Era Edwards Limestone capping the hills soil is thin to nonexistent, and loose limestone rocks lie about sometimes making it hard to navigate. Often the limestone is splotched with white, crustose lichen, as shown on a car-tire-sized rock above.

From a few steps away those white lichens display no conspicuous field marks to help with identification, but up close they reveal some modest details. One is that in some places the lichen's smooth, white, featureless surface becomes a bit warty and cracked in a halfway systematic manner, as shown below:

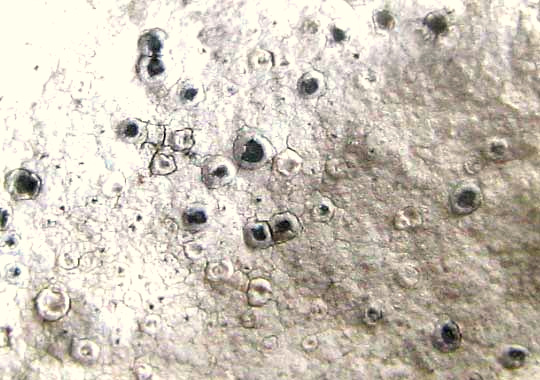

In other places small, craterlike openings with black interiors pit the lichen's body, or thallus, as shown below:

The pits are apothecia inside which fungal spores are produced. These apothecia are different from those we've seen lately in other species in that they are much smaller, and sunken into the thallus.

This lichen forming white, roundish spots on exposed limestone, with a smooth body that often cracks like dried mud, and whose surface can become spotted with tiny, black-centered apothecia appears to be ASPICILIA CALCAREA, sometimes called the Calcareous Rimmed Lichen. The species is documented practically worldwide wherever limestone rock exposes itself to the elements. In the US it is much more commonly noted in the arid West than the humid East. It is documented growing on canyon and archeological rock-shelter walls at Amistad National Recreation Area just west of here. In rainy Europe it appears to be common, and much noted on old gravestones. This relative rareness in humid eastern North America but regular appearance in humid Western Europe suggests to me that there may be more than one species involved, but that's a detail for the specialists.

For us it's enough to file pictures on the Internet showing what's growing atop our hills here, placing the pictures in a reasonable pigeonhole until the right researcher comes along. And that pigeonhole, which the search engines will find, catalog and make accessible to the world soon enough, is: Aspicilia calcarea.