Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the December 16, 2012 Newsletter issued from the valley of the Dry Frio River in northern Uvalde County, southwestern Texas, on the southern border of the Edwards Plateau; elevation ~1750m (~5750 ft); N29.62°, W99.86°; USA

MINNIE'S STOMACH

The neighbor's cow, Minnie, who leaves impressive and fairly sloppy paddies here and there around the cabin, is an affectionate being who when we eat salad comes right up and nudges us, wanting some. It's impressive how much time she spends grazing grass, and mind-boggling to think of what is actually going on inside her. Basically, Minnie is a walking, mooing ecosystem at the service of microbes in her stomach.

I began thinking like this the other day when I read that in one drop of rumen fluid -- the rumen being a compartment of Minnie's stomach as well as of all "ruminants" such as goats, sheep and deer-- there are more than ten times the number of microbes than people on Earth. That's about a thousand billion microbes per milliliter. The rumen holds up to 95 liters of food and fluid, a liter being a thousand milliliters. At this point in the calculations my mind can no longer deal with all the zeros, not even being able to visualize a million of anything, much less a thousand billion a thousand times. And the rumen is just one of four of Minnie's stomach chambers packed with digestion-assisting microbes.

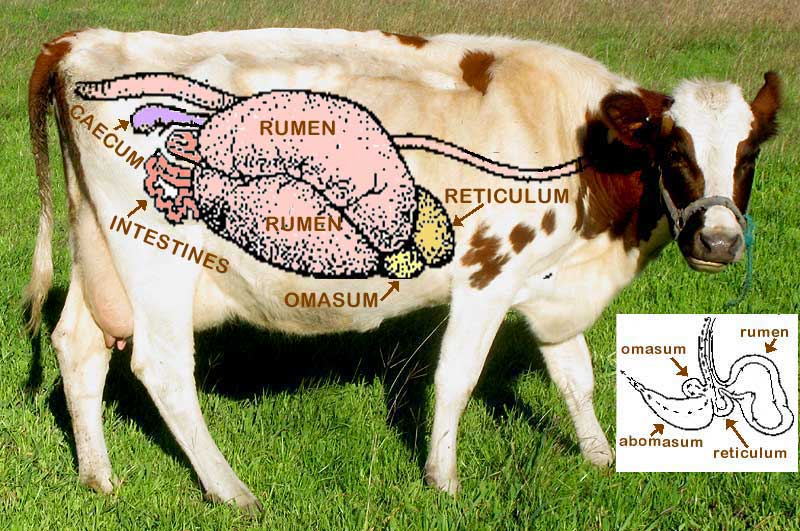

Recently while Minnie was standing looking at us beseechingly I snapped her picture, which I overlaid with a diagram of her gastrointestinal tract, as shown at the top of this page.

Minnie swallows a mouthful of grass, which then passes through the esophagus into her spacious rumen, her stomach's first chamber.

The rumen is a fermentation factory where cellulose, fiber and carbohydrates are broken down into compounds known as "volatile fatty acids." Also in the rumen microbes synthesize amino acids from non-protein nitrogenous sources. Food normally goes back and forth between the rumen and Minnie's mouth. When Minnie wants to re-chew some food that hasn't yet digested well in her rumen she regurgitates it, then stands around looking nonchalant while "chewing her cud," then when she's finished chewing, sends her food back to the rumen.

In the picture you can see the entire route her food might take in the inset at the bottom right. Following that diagram's arrows you can see that the next stop for her food after the rumen is the reticulum. Actually the reticulum is an optional stop. It's reserved for things swallowed that are very hard or impossible to digest, like scraps of metal. In fact, sometimes the reticulum is known as the "hardware stomach." On many ranches it's standard procedure to feed a commercially produced "cow magnet" to each calf at branding time. The magnet settles in the rumen or reticulum and remains there for the life of the animal collecting scraps of metal that otherwise might work into the stomach's many folds and perforate the stomach wall, seriously hurting or killing the cow. You can see a cow magnet and read about them at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cow_magnet.

The food's next stop is the omasum, which is where water and some nutrients are absorbed from the now fairly well digested food. The omasum's lining is folded like the pages of book to provide a large surface area for absorption.

From the omasum food passes into the abomasum, which is like the human stomach in that it secretes protein- and starch-digesting enzymes to further digest whatever food that hasn't been digested so far. Sometimes the abomasum is known as the "true stomach". The abomasum is shown in our inset but not on Minnie's side because if we were really looking at Minnie's stomach from the side we're on, it would be entirely hidden by the sprawling rumen.

From the abomasum food passes into the small intestine, which occupies much more space than shown in our overlay. The caecum shown on our overlay is considered to be the beginning of the large intestine. It serves as a storage organ that permits bacteria and other microbes time to even further digest whatever cellulose that may have made it that far undigested.

And, from the large intestine what once was food now passes out of Minnie, onto the ground around our cabin.