Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the August 12, 2012 Newsletter issued from the woods of the Loess Hill Region a few miles east of Natchez, Mississippi, USA

AMERICAN TOAD

Down in the deeply shaded, sublimely humid bottom of a wooded ravine below the trailer I was photographing slime mold on a disintegrating, moldering log when my elbow almost squashed a toad who all along had sat unmoving as I positioned myself here and there framing the slime. Apparently he was picking of fruit flies attracted to the slime. Slowly I pivoted the camera around, setting the shutter at a very slow 1/10th of a second because of the exceedingly dim light. You can see the toad above, the background overexposed and colored strangely as a consequence of making the dark toad show up.

I was tickled with this toad because toad identification can be tricky. To be sure which toad species is at hand I like to have mature ones. That's because atop an immature toad's head the cranial crests and parotoid glands are poorly developed, and the relative shapes and positions of those features are determinative in toad identification. Therefore, holding my breath I managed to very slowly position the camera right above the toad to get the picture shown below:

The elongate bulges below the eyes are the parotoid glands, which are glands that secrete neurotoxins -- poisonous compounds that affect animal nervous systems. The toxin produced in toad parotoid glands works mainly on the heart in a way similar to that of digitalis. In Hawaii a child died after eating a toad killed by his father in a sugarcane field. Most dogs and cats leave toads alone but those who chomp down on certain species can be poisoned, even die.

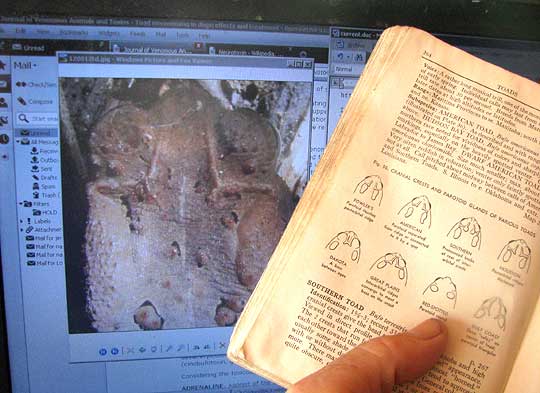

In the picture the slender L-shaped ridges bracketing the bulging eyes and above the parotoid glands are the cranial crests. In my old Peterson reptile field guide line drawings show the exact configurations of the various toad species. You can see how I used them below:

There was a perfect match, and the verdict was: American Toad, BUFO AMERICANUS. The salient feature noted is that on our toad the horizontal segments of the cranial crests do not touch the top of the parotoid glands, but their tips, at least in once instance, do curl downward and join with the glands. I'd suspected that our shady toad was an American because a second, somewhat less precise feature of the American toad is that normally only one or two large warts arise from the toad's dark spots, while on the other common species it could have been, the Fowler's, normally there are three or more. You can see that our toad's dark spots contain just one or two warts.

American Toads are common throughout forested eastern North America, except that they're missing in much of the US Deep South -- absent along most of the Coastal Plain from North Carolina to Louisiana. We're maybe 50 miles north of the southernmost point of their distribution. American Toads are one of many plant and animal species occupying a fingerlike lobe of distribution area projecting surprisingly far south in our area, along the Mississippi River's eastern banks. That's thanks to the sheltered bottoms of our area's deep, protected ravines eroded into the 200-feet-or-so (60m) thick mantle of loess accumulated on the Mississippi River's eastern side.

So, finally, I'm sure we have American Toads here. But also I'm thinking that Fowler's Toads also may be present, and possibly Oak Toads as well. I just need to find more adults with well developed cranial crests and parotoid glands!