The Spanish conquistadors who vanquished Mexico's vast mosaic of indigenous cultures -- the Aztecs, the Maya, the Tarascans, the Tlaxcalans, and many others -- claimed two main goals for themselves:

- converting the natives to Christianity

- enriching the Spanish Crown, and themselves

Part of the Codex Kingsborough, an indigenous Mexican complaint against an abusive encomendero, probably presented to the Council of the Indies; Codex dates from the mid 1500s and currently resides in the British Museum, London; public domain image made available through Wikimedia Commons.

During the Conquest, and often after it, Mexico's native people suffered incredible instances of violence and genocide in the name of these ambitions.

From the beginning, shrewd, despotic Spanish administrators recognized the possibilities of big business in Mexico. The new Spanish overlords enlarged the natives' preexisting mercados and systems of roads, and opened up new ones. Great numbers of indigenous were set to work producing foodstuffs and handicraft, much of which eventually made its way into mercados.

Very early in the new colony's history, the encomienda system came into being, in which large tracts of land, and the native people happening to be living on them, were granted to Spanish colonizers. The natives on these lands were forced to pay tribute, and often personal service, to their Spanish overlords.

In 1542, the New Laws of Las Casas theoretically prohibited forced labor of Mexico's indigenous people, and gradually the repartimiento system replaced the encomienda system. Under repartimiento, natives still were obliged to work and provide services for the Spanish, but this time it was for the state, and for a small wage. In practice, this usually meant that an indigenous person needed to spend about a quarter of his or her time working for the Spanish.

An interesting document from 1561 describes the visit of Spanish military tax collectors to the town of Chichota, seeking funding for the war against the northern Chichimec people. The local Spanish overlord had already sold all five tons of the town's tribute in wheat to traveling merchants.

Upon Mexican independence in 1821, the repartimiento system gave way to the even more harsh and coercive system of debt peonage. Now indigenous people were manipulated into debts they could never pay, and from that point became virtual slaves working on big haciendas growing coffee, tobacco, henequen, and other crops. Peonage was outlawed in 1915, but the practice lingered for many years.

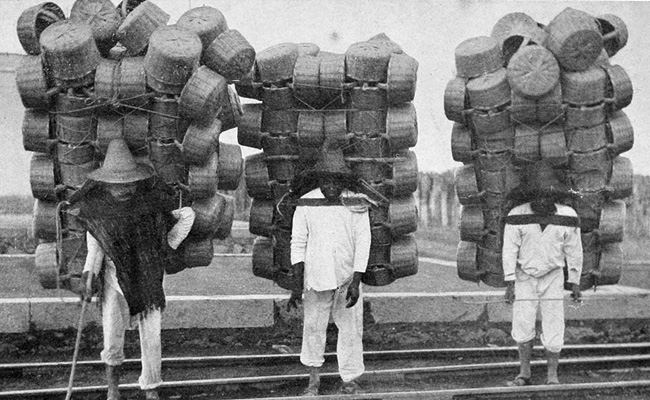

Image from the 1911 book (before the repartimiento system was outlawed in 1915) Barbarous Mexico by John Kenneth Turner; public domain image from "Internet Archive Book Images," which extracted it from the book; made available through Wikimedia Commons.

In much of Mexico, during early colonial times, indigenous people were removed from their ancestral homes and concentrated in centers where they could be more easily controlled, worked, and given religious instruction. Often this meant that native people whose traditions were centered around life in the mountains were relocated into fertile valleys, which the Spanish favored.

In north-central Yucatán state, in Hoctún, you can see the above church built in the 1700s. Its large size for such a small town recalls a time when indigenous Maya were concentrated in small areas in order to better control them, and teach them religion. In Terry Rugeley's 1996 book Yucatán's Maya Peasantry and the Origins of the Caste War, there's a revealing story about an event in Hoctún in 1829, eight years after Mexico gained independence from Spain, but when debt peonage made common people virtual slaves of the large land owners.

In 1829 the Yucatán had been divided into parishes. The home office of Hoctún Parish surely was the church in the picture. That year some Maya farmers needed new pastureland so they sent out scouts, who found good land in adjacent Cacalchén Parish. Wanting to proceed legally, they applied to Cacalchén's authorities for permission to relocate there, and permission was granted. Since in those days the Maya were obliged to work for the creole population -- creoles in this case being people born in Mexico but mostly of Spanish blood -- the Maya who moved onto the new land transferred their "fagina" (or fajina, pronounced fa- HEE-na) obligations to their new parish. The Church-sanctioned fagina was a set of obligations each Maya worker was forced to fulfill for their creole overlords.

When Raymundo Pérez, priest of Hoctún, got wind of the situation, he wrote to the bishop asking that the peasants be restored to his own jurisdiction and his own tax rolls. The Church sided with Pérez, who'd argued that if Maya peasants could go where they wanted it would constitute a fundamental threat to Church/creole authority and the tax base. Pérez's argument had been based solely on issues of power and money, with no reference at all to the welfare of the Maya.

Spanish influence was not all disruptive, though. European colonizers brought with them many marvelous things that people in the New World had never seen or heard of -- plants such as wheat, cabbage, lettuce, garlic, and onion, and animals like horses, cows, pigs, goats, and sheep. Already in 1540, just forty-eight years after Columbus first landed in America, Mexico's indigenous people were spinning wool and taking care of large herds of swine. Mercados in those days underwent incredible changes, as new plant and animal products appeared.

Before the Conquest, native Mexicans had already known how to weave textiles, but with the arrival of Spanish looms, cloth began to be produced and sold on a much larger scale. The Spaniards needed many metal objects, so the natives were set to work mining; soon metal pots and pans were being made, as well as locks and keys, cowboy spurs, and iron pieces of horse and ox harness gear.

Less than seventy-five years after Columbus first arrived in the New World, in 1565, the port of Acapulco was receiving galleons from the Philippines filled with oriental merchandise, some of which made its way into the more important mercados.

In order to assure indigenous people's dependency on the Spaniards, and thus the Spaniards' ability to control the natives, the Spanish thwarted indigenous people's efforts to provide for their own subsistence. They required their peons to participate economically in periodic urban mercados, which the Spanish assiduously controlled. Colonial governors tried to suppress all commerce other than that taking place in legally recognized markets, and new mercados could not be initiated without a license from the Viceroy.

Indigenous peoples' crops of corn and wheat often had to be registered and stored in municipal granaries, and sold at fixed prices. Among the old documents in Pátzcuaro's municipal archives is one dated 1599 in which the Count of Monterrey prohibits the sale of pigs to anyone more than fourteen leagues away. During Pátzcuaro's Friday markets, transactions taking place in the morning had to be conducted with money but, if anything was left in the afternoon, traditional bartering could take place.

Already by the end of the 1500's, many indigenous people were beginning careers as independent traveling salesmen, mostly carrying basic foodstuffs from town to town. Shipments too large and heavy for the backs of men were shipped long distances in wagons and on pack animals. During the 1700's, Alexander von Humboldt traveled through much of Mexico and was struck by the great numbers of individuals abandoning agriculture for the world of commerce. He speaks of long mule-trains "covering the roads of Mexico." "Thousands of men and animals pass their lives on the main roads "from Oaxaca to Durango, as well as on secondary roads where they carry provisions to [the mines]," he writes. During the course of a single day a native could transport goods up or down a mountain slope, from one market domain into a completely different one.

During these early years certain mercados specialized in serving as exchange points for goods passing from one region to another. Traveling merchants specializing in the markets and roads of a specific region would trade goods to other merchants specializing in different regions. Many towns where these exchanges took place were situated on mountain slopes between the hot, moist lowlands, and the cool, dry uplands. Frequently these towns developed industries processing prime materials from one zone into manufactured goods for the other.

Morelia was one town that, mostly because of its favorable location along a major trade route, eventually became an important commercial center. Here mule trains from the hot Pacific lowlands arrived carrying cotton, skins to be cured, indigo, firewood and high-quality timber, sugar, alcohol, beans, etc. Other mule-train operators from distant states would then buy these goods and carry them to their home bases, marking up prices along the way.

Mercados in colonial times, as now, occurred daily in larger populations, and weekly in smaller towns. Before the Conquest, periodical mercados typically took place every five days, but the Spanish imposed a seven-day cycle to accommodate their Christian week. In colonial times the Viceroy sometimes established regional trade fairs specifically to stimulate commerce in particular districts. Often the most rambunctious mercados were those taking place yearly on a town's Saint Day. This remains true today.