of Early Mexican Mercados

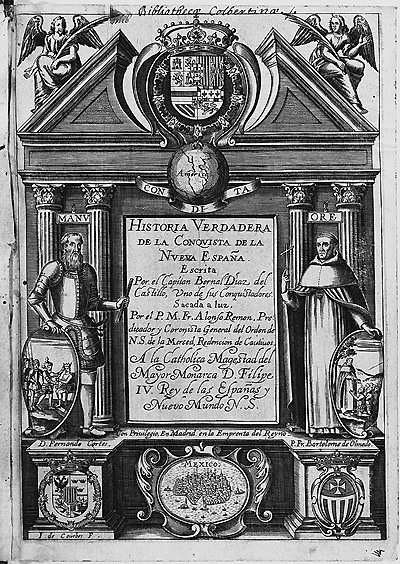

Title page of Bernal Diaz del Castillo's 1632 book Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España; Public domain image courtesy of John Carter Brown Library, made available through Wikimedia Commons.

On the morning of November 12, 1519, Spanish conquistadors had a chance to take a good look at a Mexican mercado in the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan, at the present location of Mexico City. Fortunate for us, among the conquistadors was a foot soldier named Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who eventuall as an old man would author a book describing what he saw that day, as well as all he witnessed during the entire conquest period. His book, entitled Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de La Nueva España, or "True History of the Conquest of New Spain," ranks as one of the most thrilling eyewitness accounts of history ever written.

The mercado Bernal visited that day was in a western Tenochtitlan suburb called Tlatelolco, and it was huge. Some of Bernal's soldier companions who had been in Rome and Constantinople claimed that the Tlatelolco market was larger than any they had seen. Market inspectors circulated among stalls monitoring transactions and regulating prices. Cacao beans, cotton cloaks, and transparent quills filled with gold dust served as money.

Bernal tells us that there were richly dyed textiles reminiscent of those found in the silk market of Granada. He saw finely crafted jewelry of gold and silver, and toys constructed in the forms of birds and fishes, with scales and feathers meticulously crafted of gold and silver, encrusted with precious stones, and with movable heads and bodies. There were fine vases and, especially appreciated by the soldiers, hatchets with blades of copper alloyed with tin, nearly as effective as the conquistadors' iron ones.

"We go on and speak of the sellers of beans and sage and other vegetables and herbs," narrates Bernal, as if the whole fantastic scene still swims before his eyes. "We go to those who sold chickens, turkeys, rabbits, hares, deer, and ducklings, little dogs and other such things, each in its part of the plaza. We speak of the fruit sellers, of they who sold cooked things, porridges and giblets, these also in their own places. Well there was every kind of pottery, made a thousand ways, from large earthen jars to little jugs, which were set apart; and also there were those who sold honey and candy and other delicacies made like nougat. And those who sold wood, boards, cradles and beams and three-legged stools and benches, all in their places. We go to those who sold pine wood and other such things... "

In those days mercados were such booming enterprises that they often lasted into the night. An early European traveler making a night visit to the mercado at Tzintzuntzan, capital of the Tarascan nation, found it lighted with so many torches that it evoked for him the image of Troy in flames.

Cacao beans used as money, as displayed in an unnamed museum; copyright free image courtesy of "Tamorlan" made available through Wikimedia Commons.

As Bernal reports, at this time, throughout much of Mexico and Middle America, cacao beans served as the principal currency. If their value dropped as a result of overproduction, they were simply taken out of circulation, made into chocolate, and consumed. Hungry insects and natural decay, as well as the fact that with time the beans shriveled and lost value, made hoarding impossible. On the other hand, because of their high value, cacao beans were regularly counterfeited. The beans' skins could be carefully lifted, the flesh removed, and then the empty bean skin could be replaced with wax, dirt, or pieces of avocado rind.