Picture by Linda Adams of California

The simplest kind of pottery, one baked at relatively low temperatures, can be called unglazed earthenware. This is nothing more than moist clay baked until it is hard. It is "unglazed" because clay particles on the pottery's surface have not melted to form a vitreous, or glassy-smooth, surface. Unglazed pottery is rough to the touch.

The animal figurines and pottery produced by María Lopez Lopez in Amatenango del Valle, Chiapas, introduced in our "suppliers" section, were unglazed earthenware. María simply placed her clay creations inside a stack of firewood, set fire to the heap, and hoped for the best. With such uncontrolled firing, probably it was inevitable that many of her pieces cracked as they were baking. Bricks and terra cotta are forms of unglazed earthenware.

Pottery from Capula, Michoacán showing characteristic "capuleado" painting technique consisting of multiple dots on a plain, pastel-colored background; copyright-free image courtesy of Fernando Hernández Ramírez made available through Wikimedia Commons.

Pottery from Capula, Michoacán showing characteristic "capuleado" painting technique consisting of multiple dots on a plain, pastel-colored background; copyright-free image courtesy of Fernando Hernández Ramírez made available through Wikimedia Commons.If earthenware is baked with such high temperatures that the clay on its exterior acquires a slight glaze it can be called lustrous ware. If ordinary clay is coated with a truly glassy coating, then it is glazed ware. Some would say that real glazed ware must contain lead. However, now that everyone worries about this dangerous heavy metal soaking into food cooked in lead-containing pottery, most vendors swear that their glazed pottery contains no lead. Lead poisoning is such a serious matter that I'm not sure what to advise if an extremely lustrous pot catches your fancy.

Stoneware is pottery made of high-silica clay, which when fired becomes particularly hard and impervious to liquids. The term graniteware can be used for pottery made of high-silica clay that is light colored and coated with a glassy, or vitreous, glaze traditionally containing lead. Porcelain is the most delicate type of pottery. It is made of kaolin, a very fine-grained, white clay, and is not produced by traditional Mexican artisans.

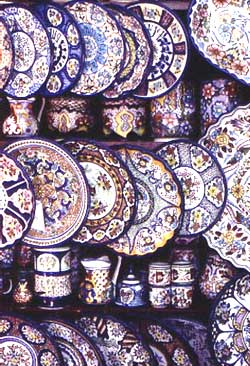

Talavera pottery in Puebla; copyright-free image courtesy of Adrián Cerón made available through Wikimedia Commons..

Among Mexican towns producing the finest pottery are Tonalá and Tlaquepaque near Guadalajara. In Michoacán, near Pátzcuaro Lake, the ancient capital of the Tarascan Indians, Tzintzuntzan, still produces superb traditional pottery. In Oaxaca, in the town of San Bartolo Coyotepec, about six miles south of Oaxaca City on Mexico 175, a famous black pottery is available in both glazed and unglazed forms. A similarly fine, green, glazed pottery comes from Santa María Atzompa, on a small road just west of Oaxaca City. Potters in both towns use the same clay; the black pottery is black through and through, but the green is black inside, with a green glazing.

Puebla produces some of the most ornate, commercially successful pottery, some of which is shown above at the right. Remember to take a look at the introduction to talavera provided by the Paria's Javier Pérez Domínguez, in the "Suppliers" section.

Tree of Life by Guillermina Aguilar Alcantara of the Aguilar family of Ocotlán de Morelos, Oaxaca; copyright-free image courtesy of "Friends of Oaxacan Folk Art" made available through Wikimedia Commons.

Tree of Life by Guillermina Aguilar Alcantara of the Aguilar family of Ocotlán de Morelos, Oaxaca; copyright-free image courtesy of "Friends of Oaxacan Folk Art" made available through Wikimedia Commons.Mexico's ceramic output is hardly limited to pottery. Among the most popular baked-clay items purchased by tourists in central Mexico are árboles de la vida, or "trees of life," many of which are produced in Metepec, a southeastern suburb of Toluca in México state. These trees, which can stand several feet tall, may be fantastically elaborate, and bear among their branches multitudinous figurines of animals, flowers, fruits, angels, and just about anything. The one at the left is more typical of the traditional style.