Different opinions are expressed about how to divide and subdivide North America's archaeological time periods. For more details on the matter, check out Wikipedia's detailed and possibly confusing List of North American Archeological Periods page.

PALEO-INDIAN PERIOD

Much debate centers around when and how the first Paleo-Indians arrived in North America. Some say that the earliest humans in the Americas arrived about 13,000 years ago, though usually it's agreed that they arrived 15,000 to 20,000, when probably they crossed on a land-bridge between Siberia and present-day Alaska. Some claim that people may have arrived in the Americas as early as 40,000 years ago, or even 50,000, and that maybe they took completely different routes than through Alaska, probably arriving by boat. Moreover, possibly certain even older populations established themselves, and then vanished. A review of current thought on the matter is available on Wikipedia's Peopling of the Americas page.

Whatever the case, it's clear that the first Americans fed themselves mainly by hunting the "big game" typical of North America at the end of the last ice age. These included mastodons, giant sloths, short-faced bears, several species of tapirs and peccaries, horses, American lions and more, now extinct, possibly hunted to extinction by the first Americans. American animals hadn't co-evolved with humans, and possibly hadn't evolved the instinct to avoid us.

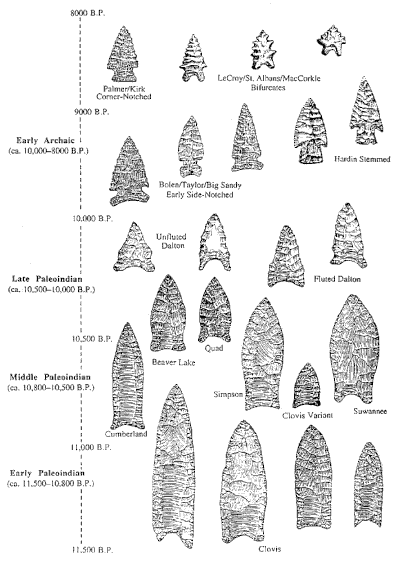

Various early projectile point types from the southeastern US; image courtesy of National Park Service

Various early projectile point types from the southeastern US; image courtesy of National Park ServiceAs the first Americans dispersed across the continent, it can be assumed that different groups developed different traditions and customs, mostly due to variations in local ecology. Perhaps the first distinctive Paleo-Indian group to be easily recognized today was the Clovis Culture, lasting from about 13,000 to 11,000 years ago. For hunting, this group produced a distinctive "Clovis Point," labeled at the bottom of the drawing at the right.

In the drawing, which shows various kinds of early projectile points, the points are arranged so that older Clovis points appear at the bottom; note the time scale at the left. The collection indicates that the earliest Paleo-Indian stone points in general were larger than during later times, plus the basic form changed over time. In the drawing, "B.P." means "before the present."

In the Lower Mississippi Valley it appears that the only credibly dated Clovis points documented within the loess zone -- and these along the margin -- are those occurring at a site known as Carson-Conn-Short, beside Kentucky Lake in Benton County, Tennessee. The 2020 study by Mark Norton entitled "No. 20, Carson-Conn-Short, 40BN190, A Paleoindian Site in Benton County Tennessee" reports on excavations made at the site between 1992 and 2014. Many flake tools and blades not definitely of Clovis type were found, but there was one "Clovis Preform," preforms being egg-shaped or triangular rocks which have been flaked on both sides using percussion and pressure flaking techniques; they are the beginnings of useful tools such as knives or projectile points.

After the Clovis came the Folsom Tradition, lasting from about 10,500 to 6000 years ago. However, so far identified and dated Folsom Points haven't been found in our area. The closest they turn up to our region is the Texas/Louisiana border to the west, and western Illinois just north of St. Louis, to the north.

Dalton Points; image courtesy of the US National Park Service

Dalton Points; image courtesy of the US National Park ServiceThe Dalton Tradition lasted from around 12,000 to 9,500 years ago, and is seen as forming a transition from the "Late Paleo-Indian" part of the Paleo-Indian Period, into the Early Archaic Period. Dalton Points lack the long, deep "flutes", or depressions, chipped into the sides of most Clovis and Folsom points. They bear only small flutes, or no flutes at all. Their bases typically bear "ears" that sometimes flare outward.

According the Encyclopedia of Arkansas, Dalton Period page, over 750 Dalton sites have been recorded in northeast Arkansas alone. Apparently most of these sites appear to be temporary camps set up for gathering and/or processing resources. Dalton Points occur throughout most of our region.

ARCHAIC PERIOD

Archaic societies in the Americas; yellow for hunter-gatherers, green for simple farming societies, and golden for complex farming societies; the small circular spot in our area denotes the Poverty Point Culture; image courtesy of 'Moxy' at English Wikipedia

Archaic societies in the Americas; yellow for hunter-gatherers, green for simple farming societies, and golden for complex farming societies; the small circular spot in our area denotes the Poverty Point Culture; image courtesy of 'Moxy' at English WikipediaAs various Paleo-Indian cultures adapted to post-glacial times and their social and technical skills grew more complex, the Paleo-Indian Period gradually gave way to the Archaic Period. The Archaic Period is commonly supposed to have begun maybe 10,000 years ago and to have lasted until around 3000 years ago. The Archaic Period is regarded as transitional between post-glacial Paleolithic big-game-hunter society, through a long period of hunting and gathering, to the Woodland Period, during which ever-more sophisticated farming practices enabled complex, more sedentary societies to form.

An interesting feature of the long-lasting Archaic Period is reflected by the map at the left. During Archaic times in South America and Mexico complex farming societies formed, indicated in orange on the map. These farming cultures were surrounded by simpler societies which practiced less sophisticated farming techniques, shown in green. However, at this time, all of North America's Archaic groups were of the less advanced kind, mainly relying on hunting-gathering.

Mound A at the Poverty Point site, Louisiana; copyright free image courtesy of "Kniemla" made available by Wikimedia Commons

Mound A at the Poverty Point site, Louisiana; copyright free image courtesy of "Kniemla" made available by Wikimedia CommonsHowever, in the above map, in North America, note the small circle in the Lower Mississippi Valley, designated as Poverty Point Culture.

The Poverty Point Culture manifested from about 3750 to 3400 years ago. Over 100 sites have been identified as Poverty Point Culture. As suggested at the left, mound building was important to this culture, with work on some mounds continuing for hundreds of years. Poverty Point people had many interests other than the hunting and gathering practiced by neighbors surrounding them. Poverty Point artifacts include clay female effigies, simple thick-walled pottery, stylized polished stone beads depicting owls, dogs, locusts and such. They constructed agricultural hoes, and formed crude human figures, thought to have been used for religious purposes.

Projectile points found at the Jaketown Site; image courtesy of US National Park Service

Projectile points found at the Jaketown Site; image courtesy of US National Park ServiceIn fact, it's been suggested that the Poverty Point Culture -- centered among our Loess Hills of the Lower Mississippi valley -- was possibly North America's first culture to acquire a social structure complex enough for organizing a tribal system. Poverty Point villages extended nearly 100 miles (160kms) from both sides of the Mississippi River. Still, today there's little to see of them among the Loess Hills themselves. The Jaketown Site, in the bottomlands near Belzoni, Mississippi, about 12 miles (20kms) west of the Hills, is part of the Poverty Point culture. Projectile points found there are shown at the right. The site itself consists of two earthwork mounds which haven't been excavated.

WOODLAND PERIOD

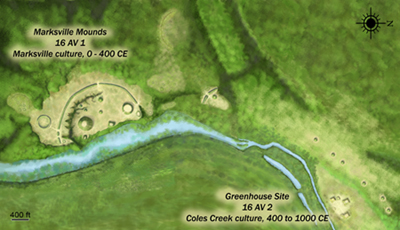

The Woodland Period lasted, according to many experts, from about 3000 years ago until European contact. In broad terms the period is viewed as a time when trends already begun in the Archaic Period continued, but diversified and grew ever more complex in nature. This greater sophistication was expressed mainly in stone and bone tools, leather crafting, textile manufacture, agricultural techniques, mound construction, and spiritual/religious practices. Artist's reconstruction of the Marksville Mounds Site, whose contacts with the Hopewell Interaction Sphere surely affected indigenous life among our Loess Hills; copyright free image courtesy of the artist, Herb Roe, and Wikimedia Commons

Artist's reconstruction of the Marksville Mounds Site, whose contacts with the Hopewell Interaction Sphere surely affected indigenous life among our Loess Hills; copyright free image courtesy of the artist, Herb Roe, and Wikimedia CommonsAn early flowering of the Woodland Period is recognized as the Hopewell Tradition or Culture. It developed between about 2100 years ago and 1500 ago. The "Hopewell Interaction Sphere" consisted of numerous widely dispersed populations connected by a common network of trade routes.

Marksville interaction sphere; copyright free image courtesy of the artist, Heironymous Rowe, and Wikimedia Commons

Marksville interaction sphere; copyright free image courtesy of the artist, Heironymous Rowe, and Wikimedia CommonsThe map at the left shows the Marksville Culture "interaction sphere" extending beyond the Lower Mississippi Valley. The interaction sphere emanated from a site known as Marksville Mounds, which lies just across the Mississippi River in Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana. This site may be thought of as the "southwestern outpost" of the much larger, more northeastern Hopewell Culture. The Marksville Prehistoric Indian Site has its own Wikipedia page. The Marksville Culture is considered ancestral to the later developing Loess Hill Natchez and Taensa people.

The latter part of the Woodland Period is recognized by numerous experts as manifesting a mosaic of traditions known as Mississippian Cultures. Some experts find this great diversity of complex indigenous societies impressive enough to propose a new formal period of it, the Mississippian Period, lasting from about 2800 years ago until European contact.

Map of Mississippian Cultures; copyright free image courtesy of Heironymous Rowe & Wikimedia&Commons

Map of Mississippian Cultures; copyright free image courtesy of Heironymous Rowe & Wikimedia&CommonsThe map at the right suggests how various Woodland cultures related to one another. Keep in mind that this state of affairs developed from the earlier-mentioned, earlier-occurring "Hopewell Interaction Sphere." To see a larger version of the map more clearly showing the names of individual sites, click on the map.

Mississippian archeological sites found among the Loess Hills of the Lower Mississippi Valley include, from western Kentucky south to southwestern Louisiana, the Wickliffe Mounds, Chucalissa, Winterville, Holly Bluff and the Emerald Mound sites.

Artist's conception of the Emerald Site begun about 750 years ago; copyright free image courtesy of Herb Roe and Wikimedia Commons

Artist's conception of the Emerald Site begun about 750 years ago; copyright free image courtesy of Herb Roe and Wikimedia CommonsOne of those sites, at Emerald Mound, is portrayed at the left as it looked during its heyday. Emerald Mound was erected just north of present-day Natchez, Mississippi. Today there's no hint of the buildings shown in the illustration, except for a lesser mound atop the main mound indicating the earlier presumed main temple.

If you examine the above links to individual archaeological sites and cultural maps, you'll get a fair introduction to the lives of indigenous Americans among the Loess Hills of the Lower Mississippi Valley, until European contact. What follows is a sidenote offered just for the fun of it.

In 1845, M.W. Dickeson, a physician in Natchez, on the loess bluffs of southwestern Mississippi, found numerous fossil bones at the bottom of a steep-walled bayou/ravine near his home. Later he carried them to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, to which he donated them. It was determined that alongside sloth and mastodon bones was a human pelvis, implicitly also fossil.

Many experts thought that the remains of an Ice-Age paleo-hunter had been found, perhaps lying next to the animals who had killed him. Others believed the pelvis to be much younger, and to have washed next to the animals from younger strata upslope. No matter, the ancient human of whom the pelvis once had been part soon became famous, both in the popular press and technical literature. He was known as "Natchez Man" -- as in "Piltdown Man" and maybe "Heidelberg Man."

Controversy raged for a long time, but when Carbon-14 dating became available, the question could be settled at last. Results: Ground sloth bones found near "Natchez Man" were about 17,840 years old, while the man's pelvis was "only" 5,580 years old. "Natchez Man" was old, but he was not a Paleo-Indian. He was Archaic.