Great Lakes from space; courtesy of NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, & ORBIMAGE

Great Lakes from space; courtesy of NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center, & ORBIMAGEWe say that, along the the west side of the lower Mississippi River, bluff-top loess is a feature left over from the last ice age. However, how do we know that an ice age ever happened? In the old days, they weren't so sure.

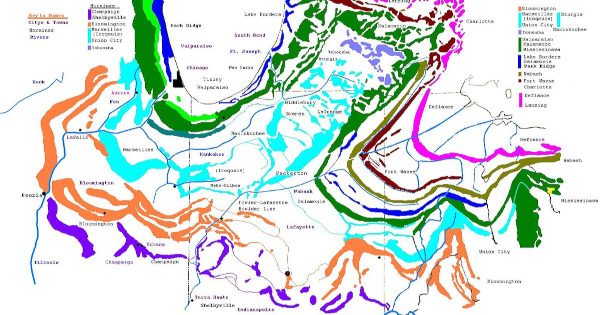

However, evidence of an ice age grew and grew until it couldn't be doubted that something unimaginably big and heavy, such as one- to two-mile thick sheets of southward-moving ice called glaciers, had pushed as far south the map at the left shows. One of the biggest pieces of evidence was the Great Lakes between Canada and the US, shown above from space. Along with many other such lakes mostly in Canada, they look like they've been gouged out by glaciers.

Glacial striations in Mt. Rainier NP, Washington, USA; courtesy of Walter Siegmund and Wikimedia Commons

Glacial striations in Mt. Rainier NP, Washington, USA; courtesy of Walter Siegmund and Wikimedia CommonsHow do we know that big, heavy objects moved across the landscape? Look at marks on the rocks at the left. On bedrock throughout the whole glaciated region such striations flow in the same direction. They show where the glacier ground down the rock, scarring it.

Not only did big, heavy glaciers grind down the landscape, but when they stopped moving southward, they left lots of debris. The debris often takes the form of moraines. Just look at the number and extent of moraines still visible today south of the Chicago and Detroit areas of the US, designated in the map below:

Terminal moraine, Wordie Glacier, Greenland; image courtesy of NASA, Michael Studinger and Wikimedia Commons

Terminal moraine, Wordie Glacier, Greenland; image courtesy of NASA, Michael Studinger and Wikimedia CommonsToday, moraines with exactly the same shape and general composition form as glaciers retreat, as shown at the left. If glaciers form such moraines now, they certainly did the same in the past.

Also, often "erratic rocks" are found, often very large ones, that have been carried southward long distances. Frequently such rocks consist of a very specific combination of minerals not found locally, but which do occur at a known location far to the north. These are considered to have been carried south by glaciers. One such erratic rock is shown below.

Glacial erratic in Mystic, Connecticut; image courtesy of 'Msact' and Wikimedia Commons

Glacial erratic in Mystic, Connecticut; image courtesy of 'Msact' and Wikimedia CommonsStudies of fossilized pollen indicate that around 20,000 years ago that part of the Lower Mississippi Valley north of about Grenada Lake in northcentral Mississippi was occupied by boreal forest, consisting largely of pines, spruces, firs, birches and willows. For about 80 miles south of Grenada Lake a transition zone occurred leading from boreal forest to evergreen forests similar to today's piney woods. Curiously, average seasonal temperatures here were not tremendously different from what we have today.