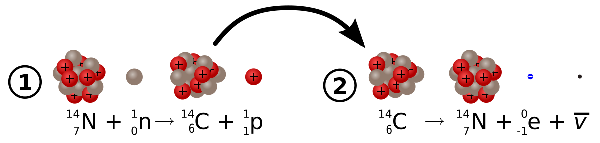

Nitrogen is estimated to be the seventh most abundant element in the Universe, and nitrogen gas, consisting of two nitrogen atoms bound together as N2, forms about 78% of the Earth's atmosphere. The above formula sketches what happens when a cosmic ray -- a high-energy particle originating from the Sun -- hits a regular atom of Nitrogen (N), as seen above on the formula's left.

To start with, a natural nitrogen atom has 7 protons and 7 neutrons, giving it an atomic weight of 14. When a cosmic ray hits a nitrogen atom, it knocks off a neutron, creating from the nitrogen atom an unstable, radioactive isotope of carbon which, having a negative charge, adds a proton. Normally the carbon atom has an atomic weight of 12, but this isotope now has an atomic number of 14, making it Carbon-14, also written as 14C.

Public domain image by "KeyboardSpellbounder" made available by Wikipedia Commons

Public domain image by "KeyboardSpellbounder" made available by Wikipedia CommonsUnstable, radioactive 14C wants to become stable, and the way it does this is by ejecting an electron -- the red ball in the simplified formula at the right -- in the process becoming a normal, stable atom of nitrogen, which it had been before being hit by the cosmic ray. Nothing prevents it from doing this, but the process takes a long time. Radioactive 14C has a half-life of about 5730 years, meaning that if you start out with 100 atoms of 14C, in about 5730 years you'll have 50, the missing 50 having become ordinary 12C. Such conversions of ordinary nitrogen to 14Carbon and 14Carbon to 12Carbon happen all the time, though relatively rarely. In Nature, one atom of 14C exists for every 1,000,000,000,000 normal 12C atoms.

Therefore, if you're a photosynthesizing plant using regular atmospheric carbon dioxide for the manufacture of sugar, or an organism consuming those photosynthesizing plants, you can't avoid having one in every 1,000,000,000,000 carbon atoms in your body being an unstable, radioactive 14C atom.

Of course, when something dies, 14C atoms cease being added to the dead remains.

In other words, if you find a snail embedded in loess, you can estimate fairly closely when it died by the amount of 14C still in its body. Something that's been dead for 60,000 years or longer has so little 14C that the dating technique becomes uncertain. However, our loess was deposited during the last ice age, which ended only 11,000-12,000 years ago, so "carbon-dating" is very helpful for us.

Back during the mid 1960s a team of investigators from Millsaps College in Jackson, Mississippi, headed by J.O Snowden, Jr. and Richard R. Priddy, pulled up to a road cut on the U.S. Highway 61 Bypass at Vicksburg, Mississippi -- a road cut through unmistakably classic loess -- scraped away part of the road cut's weathered face, and found scattered all through the loess white, thumbnail-size fossil snails, just like the ones that once caused Bohumil Shimek's heart to flutter in our "Snails were telling us" section.

Carbon-14 dating machine at the Musée archéologique du lac de Paladru in Charavines, Isère, France; copyright free image courtesy of "Patafisik" made available by Wikipedia Commons

Carbon-14 dating machine at the Musée archéologique du lac de Paladru in Charavines, Isère, France; copyright free image courtesy of "Patafisik" made available by Wikipedia CommonsEventually the shells were checked for their 14C content both at the U.S. Department of Agriculture Sedimentation Laboratory in Oxford, Mississippi, and by a company called Isotopes, Inc., of Westwood, New Jersey.

When the reports on estimated dates of snail death came back, they were simply glorious to behold. The snail-shell samples had been taken at five different levels. Shells in the topmost sample were judged as 17,850 years old, give or take 380 years. The middle sample was placed at 19,250 years old, give or take 350 years. The lowest sample registered 25,300 years old, give or take 1,000 years.

In short, the snails tell us that our loess was deposited during a long period between about 25,000 and 18,000 years ago, which we've known all along was toward the end of the last ice age.