MUSCADINES & PAWPAWS

Suddenly the air has dried a bit. The eternal heavy humidity has let up and sleeping beneath the mosquito net in the woods is even more pleasant as, at least toward dawn, it grows coolish.

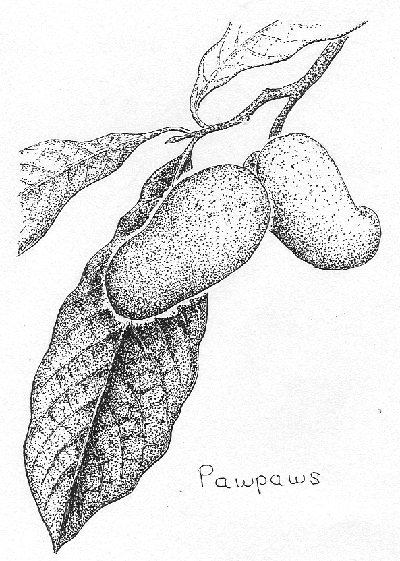

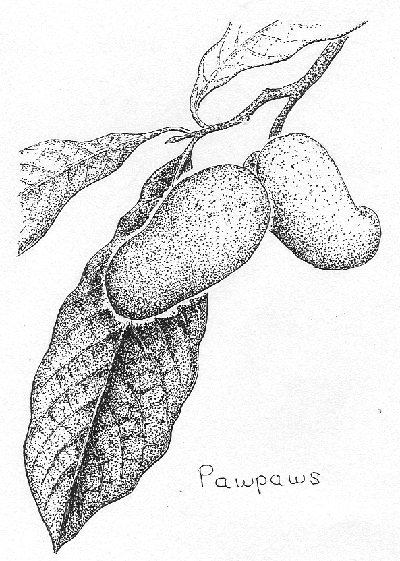

The early-fall feeling diffuses through the daytime woods, too. You can't walk far without turning up a few dark purple, luscious muscadine grapes lying on the ground, or some musky, yellowish-green pawpaws. This year our muscadines are as abundant as ever, but the crop of pawpaws is only normal, not the bounteous amount of the last couple of summers.

We have several species of wild grape in the forest here. Muscadine Grape, Vitis rotundifolia, is easy to distinguish with its small leaves only about three inches across, and its large, thick-skinned, purple grapes. The leaves are glossy on both sides and crisp like the paper of a high-quality ad in a glossy magazine. The muscadines' thick, high-climbing stems sprout long-dangling, reddish aerial roots. If you're still unsure whether you have a muscadine, then here's one final secret:

Break a small stem off the big grapevine and with your knife cut down the middle of the stem lengthwise. Inside the stem you'll see that the wood is white but there's a brownish pith. Well, in species other than the Muscadine, at those "nodes" in the stem where buds and leaves arise, the pith is interrupted with a kind of diaphragm. In the Muscadine, the pith continues right through the node.

Sometimes the muscadines are so acid and sharp that as you saunter through the woods nibbling you want to swallow them whole, seeds and all. But then comes a pawpaw tasting just the opposite, darkly musky and sweet. One moment in a beam of dazzling sunlight, the next in a moody shadow, now a grape, now a pawpaw...

*****

TADPOLES OVER THE EDGE

During a late-afternoon rain on July 31, frogs left eggs in the dishpan in which I wash next to my trailer door, and each week since then I've reported on the developing tadpoles. About an hour after I issued last Sunday's Newsletter a storm came up and simplified the dishpan's overpopulation problem. The dishpan lies beneath an awning from which water dribbles into it. During last Sunday's rain the dishpan overflowed. I stood there in the downpour watching tadpoles flow over the edge to certain death on the ground below. I let this happen because of my realization that there were just too many tadpoles there. Even if all the tadpoles somehow made it to adult frogdom, the local ecology could never support so many frogs. I watched as about half my tadpoles went over the edge.

Standing in the rain with all my conflicting feelings, this question occurred to me: Am I not to my tadpoles in their dishpan approximately what the Creator is to us humans on Planet Earth?

Having that insight so vividly placed before me, and remembering some times in my own past when I could have used a bit of divine intervention, I thought: "Obviously the Creator has made us tadpoles and humans this way, but why wouldn't it have been just as easy to formulate us so that neither tadpoles nor humans were predisposed to commit the excesses and errors that get us into these awful situations? Why build a frog whose vast majority of offspring must die before reaching adulthood, and why build humans programmed for the arrogance and aggression that's screwing up our world right now?"

I cannot recall the path my mind took from the moment of that thought, but I can say that leading directly from it suddenly there arose a flash of insight. For perhaps a thousandth of a memorial second I understood that the moment the Creator cleaved matter from primordial energy, the die was cast for things to be the way they are, frogs and people. I understood clearly that in any Universe in which matter existed apart from nothingness or pure energy -- where there was stuff of touch and movement, stuff that interacts and evolves -- then tadpoles over the edge become inevitable, and so do hermits with hard memories and hemorrhoids.

During that micro-moment in the pouring rain I understood profoundly that without pain there cannot be pleasure, without darkness, light.

An hour after the rain, walking around still stunned by the intensity of my insight but already gradually losing the thread of thought leading to my discovery, I noticed that ants were tearing at the drying-out tadpoles on the ground below my dishpan table. Up close I even smelled the fishy odor of tadpoles coming undone.

Yet, it all seemed right. If during this last month my emotional currency had been invested in ants instead of tadpoles, I should now be as close to the ants as I am with the amphibians. And I would be rejoicing with them that during this recent rain these gelatinous packets of dark, speckled protein plopped onto the ground from above, a kind of manna from heaven, just what the Queen and her colony needed.

And I stepped into the trailer laughing at the world, laughing at myself, just laughing.

*****

RIPE MAYPOPS

Each morning a bit before sunrise I go jog. During recent days I've kept my eye on a Passion Flower vine, Passiflora incarnata, growing luxuriously on a roadside fence along my jogging route. This amazing plant, a native species also known as Maypops, is fairly common around here. Even though the vine often grows as a weed, its big blossoms (1.5-2.5 inches wide) are among the most gorgeous of our native plants.

It's not the blossoms I've been interested in seeing, however. They've been around since June through August. What catches my attention now is the fruits, which look like large, green hen-eggs affixed with a little stem. The thing is, you can eat those fruits.

If you collect the fruits when they're too green, inside they are white and pithy, and the taste is bitter. However, if you wait until the fruit's skin begins showing a few spots and a slight yellowness, and the flesh is a little yielding, then the insides are filled with small, soft seeds contained in wet, translucent, packets of sweet-tasting goo.

This gooey stuff is very fragrant and sweet. It's hard to believe that you can walk up to something lying on the ground -- for the fruits usually fall off once they're ripe -- break open the leathery shell, and scoop out something edible that tastes so good.

The main problem most people have with passion-fruit goo is that it's filled with many seeds a bit smaller than grape seeds. I just chew the seeds and swallow them. They're soft and don't taste bad, and if you eat the goo from only a few fruits it won't hurt anything.

Passion Flowers are members of the Passion-flower Family, a family whose approximately 400 species are nearly entirely limited to the world's tropics. We have two species here, which are thus remarkable in that they thrive in the Temperate Zone. In traditional Mexican markets I love to buy Granadillas, which are baseball-size fruits of the Brazilian Passiflora edulis. They provide more edible material per fruit than ours, but ours may taste even better.

*****

COMPUTER, COMPOST, BULLFROG & ART

This week I've had awful computer problems and I'm still not back to normal. For most of four solid days I've struggled to patch together parts from three old computers to make something that works. This Sunday morning I'm still having problems, needing to pound the table to get an image onto my screen.

Thursday I took a break from my computer woes by going to say hello to the compost heap. I found it happily cooking along at an interior temperature of 138° . For a while I just stood there reflecting on how my activities could be so disrupted by a few electrons inappropriately digitally distributed, yet, simply by lying there, all along this compost heap had been accomplishing exactly what it wanted.

My first thought was that, by keeping things simple, that heap had managed to reach a kind of Buddhist perfection. Its high cooking temperature resulting from the breakdown of complex organic materials into basic soil-building nutrients and particles seemed to me a kind of biological equivalent to the path to nonexistence and Nirvana. But then I remembered that, actually, a compost heap is quite complex. Its proper function depends on the well-timed interaction of trillions of living individuals and thousands of kinds of individuals, from bacteria to millipedes.

In fact, it occurred to me that nothing is really completely simple. For example, This week Larry Butts up near Vicksburg sent me a picture of a bouquet he'd created for his wife. It was wonderful, containing thistles, honeysuckles, and lots of other "weeds" and wildflowers from along his gravel road. One might say, "Oh, it's so pretty because he's simply stuck a bunch of pretty things together," but a closer look reveals that the arrangement was successful largely because it adhered to certain laws of proportion based on complex geometry, and color aesthetics that were actually quite subtle.

Likewise, some would say that in terms of maturity and sophistication no human society has ever surpassed that of China's ancient T'ang Dynasty. Among the most treasured relics of that society are haiku by the great T'ang poets. And what, at first glance, is more simple than a haiku? Here is one I recently wrote while sitting next to our pond:

A silent bullfrog...

Of what good is such a thing

Just watching me sit... ?

At first glance, it's childishly simple, saying almost nothing. Yet, if you reflect on it awhile, maybe you can see that this poem invites questioning of the definition of "good," and one's own expectations. Maybe even it reveals something about me as I question these particular things in this particular manner... all in 17 syllables!

It's as if in life at first everything is simple, but then you see how complex it is, but if you live long enough and if you mature enough, eventually you find simplicity in that complexity, but expressing that simplicity is not simple at all, for that, maybe, is the domain of art.

Anyway, if during upcoming weeks I miss putting out a Newsletter or two, it's because my old homebrew computer has finally bitten the dust, and I'll be back online eventually -- unless I lose track of time while keeping my compost heap company.

****

BIG, YELLOW PEARS

As pawpaws disappear from the woods, the pears in our little orchard ripen. I don't know what variety these pears are but I suspect they are an old one. They're yellowish green, mottled with green and golden blotches. They can be larger than a softball and often the bigger ones are more spherical than pear-shaped. They are very hard, crisp, fairly grainy, and tart. In fact, I prefer them cooked, since that mellows the tartness and makes them sweeter.

Each morning during pear season I prepare a skillet-size hunk of "bread" consisting of about 4/5ths sliced pears, and 1/5th batter made of half flour and half cornmeal, plus a couple of sliced jalapeño peppers. I like the hot-sweet taste embedded in a basic offering of cornmeal. I bake the "bread" over a wood fire until it's leathery on both sides, and golden, speckled with black burn marks. I thump the bread to see if it's ready, and the thump sound reflects the tough exterior, and moist, gooey interior. When the thump sounds just right, I salivate like Pavlov's dogs. I don't know if this recipe would taste good prepared in a regular kitchen. Often I've tried to prepare my hermit meals in civilization, but usually such concoctions don't travel well. Maybe it's the different energy-wavelength radiated by a campfire, or maybe it's the woodsmoke's flavoring.

When I first visited this plantation in the early 80s we had a sizable orchard with many varieties of apple, peach, plum, cherry and pear, but now nearly all the trees have died from diseases and neglect. Only this variety of pear survives, and its trees remain handsomely robust. Each year -- unless a late frost nips the flowers -- they produce a bounty. You walk up to a limb almost at the breaking point with so many pears, give it one little shake, and a dozen or more big fruits tumble to the ground.

If I'm ever dying and have the time to think back on the more wonderful moments of my life, I think I'll try to remember a few of my best pear-storms -- of when my tug on certain overladen branches released avalanches of a bushel or more of huge, profoundly tart, yellowish-green fruits that bounced in the tall green grass below sounding like galloping horses, and of course a few landing on me, as if the tree were a playful friend.

*****

MOON DREAMS

We had a full moon last Sunday, September 2, but the rains hid that fact. By Wednesday I could start sleeping outside again, and then the remnants of that moon very much became a part of each of my nights. At dusk there would be no moon and the forest would be uncannily dark, but then I would sleep a few hours and when I awakened deep inside the night I could look through the trees to the broomsedge field beyond and see that every clump of grass, every bramble and bush was chiseled perfectly in silver, and that the moon shone painfully bright above.

During full moons my dreams are much more vivid, colorful and memorable than other times, and I astonish myself with what images and ideas emerge from inside me. Well, studies show that it's the same with many people. Both crimes and suicides increase during full-moon times.

I used to hypnotize people so on full-moon nights when I awaken throughout the night and see the moon at several of its positions, it feels as if someone or something out there were probing and manipulating my psychology. I feel the moon drawing me outward, through the tree-branch silhouettes, though into what beyond that I cannot imagine. At these times the calls of the Barred Owl seem very significant.

But then dawn comes and the Cardinals sing, and I know that I have only experienced the moon crossing overhead during the night.

*****

HYPOGLYCEMIA & SPIDERS

I’ve been watching a Garden Spider lately. This has got me thinking about an experiment I read about long ago. Different chemicals were given a spider to see how each chemical would affect the spider's web. Most striking was how the spider given marijuana's active ingredient produced a sloppy web with many incorrect connections and holes. On the other hand, when the spider was given the active ingredient in LSD, the web produced was perfect, as if the chemical had increased the spider's power of concentration.

It makes one wonder how much our own realities are affected by whatever chemicals or hormones happen to be flowing in our veins at the moment. Could just the right knock to my head or a change in my diet convert me from a happy hermit to a nervous land-developer overnight?

I wonder about these things a lot, especially because I am hypoglycemic. If I happen to stoop for a while and then stand up quickly, things go black and I'm lucky if I can keep standing. Then as blood sugar slowly returns to my brain I become able to take a few steps, though I seem to see things through a tunnel. Finally I return to full consciousness. I think that this happens to everyone, but with me it is a daily, sometimes hourly event.

Thing is, during those few seconds when I'm able to walk but see things as if through a tunnel, I think I'm fully recovered, and actually feel happy that once again I can concentrate so clearly on the ground before me and walk with such self assurance. It's only moments later when I'm really normal that I remember back to my tunnel-walking moments just a second or two earlier and realize that as I'd tunnel-walked my thoughts and insights had been profoundly limited.

In other words, several times a day I remind myself that the very dumb can never know just how dumb they are. I am also struck that during the first few moments of "being myself," I can still recall exactly how it was to be "tunnel walking," and I am appalled at how self-centered and narrow the tunnel-walking headset was.

Moreover, how can I know that when I'm "normal" there isn't an even more lucid state beyond that, one in which I could "be myself" if I only had the brain to go there?

In fact, because of very brief moments of insight accomplished during moments of meditation, I am sure that those higher levels of enlightenment do exist.

Recollections of insights understood during those brief moments of enlightenment have a little to do with why I am now a hermit in the woods. However, now in my "normal" state, I am really too dumb to explain to you clearly how my reasoning works.

*****

RED-BELLIED WOODPECKERS

Now that the mosquitoes have calmed down I've returned to my old habit of late each afternoon biking over to the hunters' camp, sitting on their porch, and reading. One day this week while absorbed in To Kill a Mockingbird I heard a racket in the Pecan tree above me and looked up just in time to see two Red-bellied Woodpeckers all in a wad, each with a bit of the other in its beak, clawing and beating wings against one another. They tumbled 20 feet, thudded onto the ground next to me, and I thought that surely they'd both be crippled.

But they just fought a little longer, then one flew off horizontally and the other vertically. I guess the one who went vertically was the winner.

Both in my home area in Kentucky and here, in upland situations Red-bellied Woodpeckers are the most common woodpecker species, and for that reason alone usually I don't get too excited about seeing one. However, over the years I've experienced a sort of creeping admiration for the species.

First of all, when I began traveling in the American tropics I came to realize that our Red-bellied species was just the local expression of a complex of very similar species distributed all the way into South America. In northern Mexico's mesquite plains the Golden-fronted Woodpecker is everyplace, and looks and sounds almost like our Red-bellied, just a little rangier. In pine forests farther south the Golden-cheeked Woodpecker looks almost the same, but with black spectacles. The Yucatan Woodpecker also looks almost the same, but it's a pygmy version. And on it goes. What a pleasure to behold variations on a theme you grew up with, thinking that that theme could be sung only one way.

Once this spring as I lay atop my trailer one Saturday morning listening to the radio a Red-bellied was excavating his nest in a Pecan tree's nearly horizontal limb about 30 feet above me. His hole entered from the limb's bottom surface so as he dug inside the limb sawdust tumbled through the hole in his floor behind him and rained onto my camp. About every minute he'd poke his head from this hole with his beak so wide open that you could see his long tongue as he gasped for breath. Well, if you're inside a limb chipping at wood, there are no windows, your body is blocking air coming into the hole behind you, so it must get awfully stuffy.

He looked funny the way his head poked from the bottom of that limb, with his beak wide open and his tongue lolling all around. But instead of laughing I was struck with the realization that here was just another regular good schnook doing his best at a rough job. He was like all of us facing tasks that leave us a bit washed-out and silly feeling. Nowadays when I'm almost feeling sorry for myself after computering all day, my back muscles burning, and I'm a bit groggy, I just remember that fellow with his tongue hanging out.

*****

SNEEZE WEED ALONG US 61

Wednesday night a limb fell from a large Pecan tree near where I sleep in the forest. It knocked out my electricity and sent a voltage surge right through my surge protector, and knocked out my computer's modem, even though I had turned off the computer. Consequently on Thursday I had to make one of my infrequent runs into town, for a modem at WalMart.

Right next to the pavement along US 61 there dwells a thin line of yellow-flowered weeds about a foot tall, and they accompany the pavement's edge for miles and miles. The same plant has been blooming for a couple of months in the middles of the more seldom-used gravel roads on the plantation. It's a tough little organism producing surprisingly pretty blossoms and fragile-looking threadlike leaves. This is Sneeze Weed, or Bitterweed (Helenium amarum) in the Sunflower family. I doubt that it makes anyone sneeze since it doesn't produce powdery pollen like ragweed or grasses, but if you taste its leaves you'll understand why it’s also called Bitterweed. The plants contain a narcotic poison and when cows eat them their milk tastes bitter.

It's worth thinking about how Sneeze Weeds form their thin line next to the pavement. Their zone of occupation is only about a foot wide in most places. Clearly they cannot live right next to the pavement, yet neither do they survive farther away, where roadside grass appears. They have evolved for a very specific sandy, dry habitat and do not range far beyond it. Their long taproot helps them survive droughts in the sand, and frequent mowing and grazing. They are native to the US Southeast, Texas and Mexico, but in recent years have spread to northern states along gravelly highways and into sandy pastures.

*****

TWO-STRIPED WALKINGSTICKS

At this time of year around my trailer, especially under it, there appear Two-striped Walkingsticks, Anisomorpha buprestoides. I never saw this species before I came here. The species often shows up with the much smaller male riding the big female's back as they mate

Once I identified the species and learned that it wouldn't bite or sting me, I picked it up, wondering how such a seemingly defenseless critter could survive, for I see them all over the place, in plain view. Then the big female squirted a drop of milky stuff on my finger. I smelled it. It didn't have much of an odor at all, but I instantly began sneezing, and I sneezed for about five minutes.

Therefore, I figured out something my books hadn't told me: This species defends itself by squirting a powerful chemical at its enemies. It must be awful to get the milk in one's eyes.

*****

GOLDENSEAL

I cut my finger a few days ago and this started me thinking about Goldenseal, Hydrastis canadensis. Goldlenseal is a native American wildflower growing to our north, in deep rich woods from Vermont, Michigan and Minnesota south to Virginia, Tennessee and Arkansas. Their knotty yellow roots, or rhizomes, are ground into Goldenseal powder, and over much of the species' distribution medicinal-plant collectors have collected them nearly to extinction.

One day a couple of years ago I was coasting on my bike down the very steep grade of our gravel road as it enters the bayou between the plantation center and my place, something happened I still can't explain, and when I was again fully conscious I found myself on the ground with blood spurting from a sizable gash across my forehead. Judging from the cuts and the remains of my glasses, I had slid a good distance down the hill on my face. It's one of the qualities of a good naturalist that he or she seldom pays much attention to the path ahead, but rather gawks constantly into bushes and trees along the way. For this reason I have a long history of running into and falling over things and thus I have plenty of experience with cuts and scratches.

When I saw how the deep cuts in my face were filled with gravel and sand I knew I was in for some infections. Even if you wash such wounds, bubble out the debris with hydrogen peroxide and douse them with iodine, swelling and festering is bound to occur. I couldn't see well enough to remove all the matter from my cuts so I went to the plantation manager across the bayou. She's into alternative medicines and all she had that day was a jar of powdered Goldenseal. She packed my wounds with that golden powder, my bleeding instantly stopped, the next day my face was covered with black scabs, and when the scabs came off about a week later I was amazed at how quickly and completely I had healed.

There had been no infection, no swelling, and the scarring was not nearly what I anticipated. Never in my life has any medicine worked so effectively for me. This week Goldenseal powder did a good job on my cut finger, too.

*****

BOWL-AND-DOILY WEATHER

For about three weeks most nights have been almost chilly, making perfect sleeping weather. This week even the days were relatively cool. On Tuesday morning my thermometer read 57°, which was so cool that I wore a shirt during breakfast and heated my breakfast water for the first time in months. The morning dew numbed my toes as I walked through it. The days, with temperatures seldom breaking 85° , and a deep blue sky with abundant sunlight making crisp, black shadows, were perfect.

The dews these mornings are spectacular, and you know how pretty spiderwebs can be on dewy mornings. Especially next to the barn where dense Loblolly saplings form a green wall 20 feet high, a vast community of webs among the pine boughs shows up brightly against the dark green background.

Most of the webs there, as well as among the goldenrods in the field where the pines thin out, are spherical, grapefruit-size constructions consisting of seemingly randomly arrayed silks, inside which are built horizontal sheetwebs shaped like shallow bowls. These special kinds of webs are made by the Bowl and Doily Spider, Frontinella communis.

As this spider's Latin name suggests, this is a very common species throughout eastern and central North America. In bowl-and-doily webs, the male and female often hang upside down beneath the horizontal sheet inside the construction. If an insect gets entangled in the sheet, the spider bites it from below the sheet, pulls the prey through the sheet, and wraps it up. Sometimes a second sheetweb is built below the main one, which apparently helps shield the spiders from predators attacking from below.

The main prey I'm finding snared in these webs nowadays is winged aphids. I'm glad the spiders are helping keep these aphids out of my turnips and mustard greens.

Bowl-and-doily Spiders are mostly black, with conspicuous white or yellowish-white markings on their abdomens. From the side, the markings look like a scrawled mc. The "c" opens toward the spider's front. I can't find a good picture of this species, but if you find a web with a spider in it with an "mc" on its abdomen, you have a Bowl-and-doily Spider.

*****

SCREECH OWL WHINNYING

These cool nights are invigorating not only to me but also for an Eastern Screech Owl who most nights can be heard calling. Especially with the moon bright and the fog moving in, as has been the case most nights this week, this owl's call is eerie and evocative. I often hear the owl "whinnying," but the main call it's making now is a one-tone, pulsating sound. I'm not sure what the different calls are communicating. I read that Screech Owls are poorly studied, so maybe no one knows.

Their mating habits are interesting. Males tend to be monogamous, but some take on more than one female, and thus are "polygynous." The degree of polygyny in a population depends on food availability and population density. Bonds are lifelong, but individuals take on a new mate if the other dies. Nests are typically found in natural cavities, abandoned woodpecker holes, and hollow stumps and limbs. Screech owls don't migrate, and they usually stay alone except during the breeding season.

That explains why I'm just hearing this one owl, and occasionally see it at dawn silently winging alone from among the Loblollies near my trailer.

*****

IVY-LEAVED MORNING-GLORY

Suddenly the fence along my jogging road is pretty enough to stop and look at. That's because sections of it are overgrown with a morning-glory vine in full blossom. The thousands of flowers are 1.5 inch across, mostly pinkish violet but in some places pure white, with other hues ranging toward blue, the hues mingling with one another along the fence. Flowers are funnel-shaped, flaring widely at the mouth, and leaves are deeply 3-lobed, like little fig leaves. In some places the much-branching, slender, twining vines climb seven or more feet up telephone poles and guy wires, and in such places the bright flowers against a background of dark green leaves and blue sky beyond is spectacular.

The vine causing this show is called the Ivy-leaved Morning-glory, Ipomoea hederacea. Its flower color ranges from bright blue to the pinkish-violet of most of our flowers, to white. Flower color in most flowering plants is pretty stable, so having a species whose flower color varies so much is special. The species' leaf-shape also is variable, for occasionally you find plants with nothing but heart-shaped leaves. This is just a free-spirited vine.

Ivy-leaved Morning-glory has been a close acquaintance of mine ever since I was a kid on the farm in Kentucky. I didn't much like it then, because every year it was an abundant weed in our tobacco patches. The plants tended to emerge from the soil so close to a tobacco plant's stem that you couldn't just chop it with a hoe, but, rather, hundreds of times each day you had to bend over and pull it out individually. Moreover, if you just yanked at the vine's stem, you were bound to shred a big tobacco leaf, and then you could just feel a nickel disappearing from your pocket.

I was a very fat, rather lazy kid, so many hours of this life I have spent fuming over Ivy-leaved Morning Glories. Who'd ever have thought that as a white-beard, I'd be singing their praises?

*****

THE TROLL

This spring and summer we've experienced frequent showers, but our years-long, overall drought has continued. Brief showers have kept plants green but when in the gardens I dig four inches down I encounter pure dust.

Thus Tuesday when I spotted a freshly constructed 1.5-inch high little tower of wet mud along my bike trail across the very dry blackberry field, I knew I'd come upon a mystery. In such a parched, dusty field at the top of a rise with the water table many feet below the surface, where would fresh mud come from? And what could build such a mud tower?

On my knees and elbows I gingerly nudged the little mud turret and was surprised to find that it simply rested atop the hard-packed dust, unattached to anything. I lifted it. Below was a round tunnel entrance about 3/4-inch across. As my eyes adjusted to the tunnel's darkness I saw that the tunnel bifurcated right below the entrance, and that at least one of the resulting arms quickly forked again. And from the blackness of one of those tunnel branches someone sat looking squarely back at me.

The little being had wide-set eyes placed at the upper corners of a triangular face. On crabby legs it stepped forward and began scooping dirt as I watched, as if its ceiling hadn't disappeared. Its body was thick, white, and it glistened with wetness. Working with a certain sense of urgency, it struck me as being like a troll in a Hobbit novel. If I had been exploring Mars and come upon a new form of life in a crater at the edge of a field of frozen carbon dioxide, I could not have been more filled with a sense of observing something otherworldly.

Gradually I realized that this was a cicada nymph -- the immature stage of the cicada that lives underground, often for years, before emerging to become the "Jar Fly" that so noisily makes buzz-saw sounds in the trees these days.

But, how did the nymph produce mud from such dry ground? Also, I have seen diagrams of cicada-nymph tunnels, and they have always been simple affairs, with no forks in them. I have combed the Internet looking for explanations, but without success.

My guess is that the nymph made its mud by mingling tree-root juice with dust, for what other explanation is possible?

*****

RATTLESNAKE ALIVE

Friday morning I was working in one of the gardens when I heard my friend Master whooping and cussing. I'd never heard Master cuss so I figured he'd had a close call with a snake, and I was right. He'd been picking up limbs recently fallen from the pecan trees onto the plantation manager's lawn, and a four-foot-long Timber Rattlesnake had been coiled beneath a limb. Master had been reaching toward it when he realized what he was seeing. The snake's disruptive camouflage serves it well these days when dried-up, brown, yellow and green Pecan leaflets litter the ground.

I put the snake in a bucket with a top on it and in a pickup truck we carried it to the back of the plantation, where it was nudged over the steep loess bluff. During the whole trip, coming and going, Master never stopped telling the story of how he'd almost picked it up.

Interestingly, Timber Rattlers usually don't rattle. I heard only a couple of clicks while getting ours into the bucket. Of all the rattlers I've encountered here, only one rattled, and that one was so loud that I thought it was a cicada fallen to the ground. I was gathering twigs to burn in my campfire and, like Master, didn't see the snake until I was reaching right for it, looking around for the flustered cicada.

Anyway, when we returned to the lawn Master had to tell his story to the manager again. After he'd finished, as he was opening the truck's door a dry leaf stuck to the frame by a spider web made a crackling sound. Poor Master jumped a good yard backwards, his eyes popping and his face frozen in terror.

Here was a big man nearly as tall as I, his ebony skin instantly shiny with the sweat of fear, and his muscles taut as a mule's. How I admired his focus on that leaf, the manner by which his entire body and soul in an instant had been transformed from a rambling story-telling mode to total attention to the source of that simple crackle.

I laughed uproariously but I knew it was pointless to say that I wasn't laughing at Master's fear. I was laughing with delight, wishing that somehow I could manage such intensity of concentration while looking at the sky, the grass, the trees, the sunlight, my own hands.

How wonderful it would be to be rattlesnake alive to all things the way Master was at that moment contemplating a dried-up leaf.

*****

OTTERS IN THE DUCKWEED

Last Sunday as my Newsletters were being distributed via the modem and these miles of corroded copper wire strung through the woods and along highways, it began to rain. Before the rain had ended I went walking, not only because the forest is beautiful when it's raining, but because sometimes you can see things you don't notice otherwise.

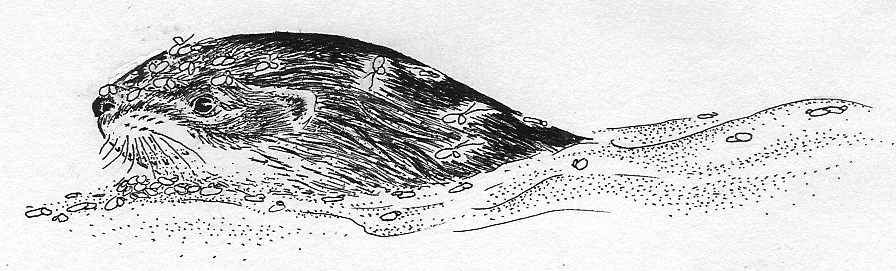

I came to a small deer-pond completely covered over with a carpet of duckweed, the little flowering plants that float atop water looking like green confetti. Working along the pond's banks were two River Otters, Lutra canadenis. The otters were so engrossed in their work that I approached to within 15 feet of them and for 20 minutes they never saw me. With my binoculars I could make out every hair on them, the quivering of their nostrils, the glistens in their eyes.

River Otters from nose to tail-tip are about 3.7 feet long and are native to nearly all of North America, except for the most deserty and frozen parts. I've seen them several times here so they must be fairly common. During winter I find them only in the swamps, but at this time of year they seem to wander across the uplands. You might recall that I reported another otter sighting in last year's September 2 Newsletter. Otters eat fish, crayfish, frogs, reptiles -- just about whatever small animal they find.

For me the most striking feature of their behavior is their playfulness. As these two otters worked along the pond's bank whenever they met they'd briefly curl into one another, each slithering around or beneath the partner with graceful twists and turns, perpetually half-playing peek-a-boo among tussocks of Water Pepper at the water's edge and among the coagulations of duckweed on the water's surface. In the muscular animals' body language you could read a kind of quick-witted laughter and it was clear that here was a level of intelligence a whole dimension beyond that of a dog or a pig, nearly the kind of wit you'd expect in a monkey or a porpoise. I was glad to be sharing the forest with this delightful and intelligent animal.

After 20 minutes the wind got up, apparently swirling my odor into the pond, for suddenly both otters stopped their cavorting and up through a thick carpet of duckweed poked their noses into the air. I moved not at all, so they did not see me. But they believed their noses and dove deeply and stayed below as I moved away.