BATHING BIRDS AT THE GATE POND

Sometimes I visit the pond near the gate and sit in deep shadows beneath a large Black Willow overhanging the pond's edge. I like this spot because it's a cool place offering a good view of the pond, and because animals in bright sunlight have a hard time seeing me. Near that spot there's a place where another Black Willow has toppled into the water, creating a confusion of shattered, brittle twigs. The birds love this spot for bathing, for there's always a twig here or there poking from the water just right for perching on while building up courage to hop into the shallow water.

One day this week, first came a mousy-gray Tufted Titmouse, its tiny black beak wide open as it panted in the heavy heat. This bird looked right and left, turned its head sideways glancing up and down, then right and left again, around and around, and finally he jumped into the water for half a second, then flitted right back to his twig to make sure nothing had gone wrong. But nothing had gone wrong, so he jumped back in, and this in-and-out cycle continued for a minute or so before he decided that all was safe and then he enjoyed an absolute paroxysm of fluttering and splashing lasting about a minute.

This titmouse flew away and another took his place, going through the entire routine just as the first one had. Even before the second titmouse finished, a female Cardinal arrived. Apparently she'd watched the titmice long enough to know that it was safe, for she hopped right into the pool and splashed with even more abandon. After the Cardinal came a Red-eyed Vireo with its snazzy white eye-stripes and red eyes. He plunged into the water for half a second, then raced to a safe twig and shuttered as if thrilled by the wetness. Then a yellow-and-black Kentucky Warbler came perching, watched awhile, but in the end just flew away. Instantly upon that departure, however, a Prothonotary Warbler with its bright orangish head came to the same twig, hopped into the water and fluttered like the titmice.

On a bright summer day, the deep green of the trees and the water, the heavy shadows, and this little train of birds all sharing in the innocent pleasures of cooling off with a bit of splashing... deep within the willow's shadows I myself felt like a placid pond being splashed in by a rainbow of perfect birds.

*****

FIREANTS AFTER A RAIN

I can live in peace with the ants that swarmed on my ceiling last Tuesday, for they were a native, non-stinging species. I wage a continual battle, however, with fire ants. As explained in last year's September 9 Newsletter, fire ants were introduced into the US in 1918, and since then their distribution has expanded over a huge part of the country, driving out many native species, causing untold suffering to animals with their stings, and causing my ankles and wrists as I write this to be speckled with itching, whitehead-like pustules resulting from their stings.

Thursday afternoon a good storm came up so just as I was hearing the rain's roar coming through the woods I chopped open a fire ant nest next to my trailer, with the hope that the deluge would drown the colony. Soon a little torrent of runoff swept before me as I stood in the outdoor kitchen watching. Thousands of white fire ant pupae and larvae swept before me. When the rain ended and the water soaked into the ground, the high-water mark beside my kitchen was outlined with a rim of white ant-pupae bodies. I do not like hurting living things, but in this camp it's either them or me. During my first year here, they almost won.

At dusk two hours later I noticed that the ground had been cleared of white pupae and larvae. Looking closer in the twilight I saw slow-moving lines of fire ants, each ant carrying a pupa or larva, and the lines converged at the old nest where already fresh excavations were taking place.

Looking down at those ant lines I felt like a chastened god, a god who had wrecked havoc upon a nation with war and pestilence, and now, seeing the grim, heroic, single-minded determination of the trudging victims, felt obliged to grant them respect. I regretted that I had been the cause of their misery, which in the dark, mud-smelling wetness of that dusk was profound.

It is not the character of each ant that I admire, for I remember that an ant hasn't brains enough to possess much character at all. It is the essence of the life-struggle in us all to which I grant my awe and respect.

For, something out there is magnificently in love with life, and that Thing has built us an Earthly theater where the greatest tragedies and most wondrous acts of heroism are played out, where the God-Thing's love is evinced by every ant, in every storm, and in the soul and mind of everyone who sees and feels.

*****

ZINNIAS FLOWERING

During my trip to Kentucky last September you may recall that between buses I wandered around Nashville's parks and streets gathering seeds. Nearly everything I picked germinated and right now Zinnias from seeds collected then are putting on a show.

Zinnias do especially well in our area because they tolerate heat, humidity and droughts very well. One reason I like zinnias is that they're native Mexican, and I have a long history with Mexico. Most of today's many varieties and hybrid zinnia strains are derived from three wild zinnia species, all from Mexico. When the murderous conquistador Hernán Cortés and his Spanish army entered the Aztec capital city of Tenochtitlan, now called Mexico City, on the morning of November 12, 1519, among the amazing things they saw for the first time were elegant, well maintained Aztec gardens occupied with zinnias.

In fact, marigolds were there, too. Both zinnias and marigolds are Mexican, and right now the first thing I see each morning is long rows of intermingled marigold and zinnia blossoms. Nowadays, each of my mornings begins with a grateful "Buenos días, hermanitas."

*****

PINE WOODS TREEFROG

Last Sunday at the edge of a soybean field a Chipping Sparrow with its handsome rusty cap and neat white eye stripe landed in a large Loblolly Pine. Bearing a beakful of insects she worked her way to the limb's end, glancing at me constantly, until she stopped at a small nest of straw wedged in a fork in the limb. Three tiny, bobbing heads with yellow-rimmed beaks and skinny necks shot up, the meal was deposited to the highest-reaching mouth, and the mother flew away for another load.

Beneath the old pine stood one of the hunters' blinds. It was a fancy, store-bought thing on shiny aluminum legs about 15 feet high. The blind itself was made of a molded black plastic material. A blind window opened right onto the nest so I climbed up for a better view.

As I cracked the blind's door, something inside jumped onto a wall and clung there. It was a species of treefrog I'd never seen before, one with smooth, gray-mottled skin and a thin, dark ridge running from its eyes to along its sides. It was the Pine Woods Treefrog, Hyla femoralis. I'm sure I've heard it before -- my Audubon fieldguide says it sounds like "the tapping together of wooden dowels" -- but this species is nocturnal and it tends to stay in treetops, so it's rarely seen. It's a Coastal Plain species, in Mississippi hardly making it as far north as Jackson.

This just made my day.

For, every species of living thing is a kind of song. The Pine-Woods-Treefrog-song rhapsodizes on life at night high in a pine tree. Its very skin matches in tone and texture old pine-bark flaked with lichen. The frog-song's voice of tapping wooden dowels bespeaks being inside a pine tree on a rainy night, needing a mate. There are bugs in the old Loblolly, so this frog is there to eat them, and its mouth is wide, its tongue quick, long and sticky, and its brain is all fixed for bug-eating.

Whenever a species is extirpated or extinguished, a song is lost, and the music of life is diminished. What an honor for me to be here where and when I am, with life still lusty with its singing.

*****

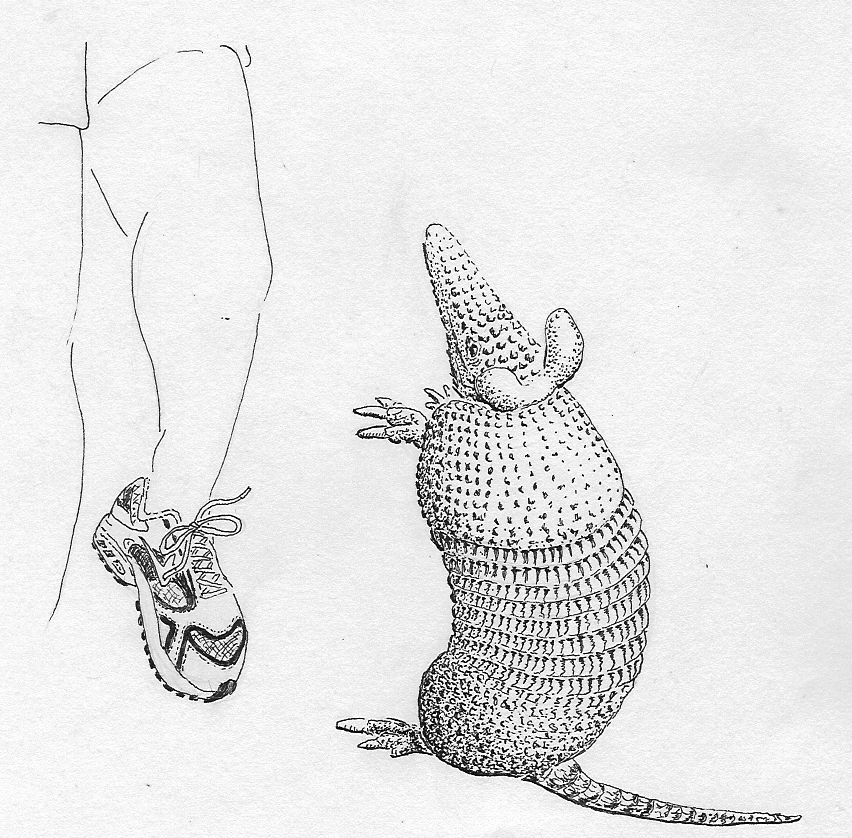

ARMADILLOS

At dawn one day this week I was jogging down a forest path near my trailer when I came upon a family of Armadillos -- a mother with 3 half-grown young. If I hadn't stopped jogging I would have tripped over these critters, but that wouldn't have been extraordinary, since Armadillos behave as if they were practically blind. Often you can walk right up to them and they will be looking exactly at you, but they will behave as if they don't see you.

On the other hand, if you get upwind from them, instantly their nose pokes into the air, they get a horrified look in their face, and they waddle off as if the Hounds of Hell were after them. My impression is that their eyes are OK, but they are attached to the armadillos' brains only very loosely, while their noses have superhighway access directly to their brains.

Armadillos have given me a lot of grief in the gardens. They burrow beneath my deer-fences, then during the night dig up enormous parts of the garden. Mostly they are carnivores, eating insects, grubs, worms and such, though sometimes they also eat a few berries, fruits and bird eggs. In the garden they couldn't care less about a cabbage plant or a tomato vine. In the gardens they look for earthworms and grubs, which in my highly organic soil are huge and juicy. The damage they do to my plants is purely incidental to their quest for earthworms.

You don't need to worry about being bitten by an Armadillo because their teeth are small, knobby things made for crunching bugs and worms, not for tearing flesh. On the other hand, if you pick one up by the tail their powerful digging claws can give nasty scratches.

You often see cartoons of Armadillos rolling themselves into cannonball-like spheres, leaving nothing but their bands of armor exposed to enemies. I've never seen an Armadillo do this. I've certainly yelled at them, jumped all around them and even poked at them with my toes trying to get them to do so, but it seems to me that ball-rolling is a rare thing with them, if they do it at all.

*****

INKY-CAP MUSHROOMS IN THE COMPOST BIN

Nowadays the first thing each morning when I go pee in the compost bin I'm greeted by one to several "inky-cap mushrooms" of the genus Coprinus emerging from the hay in the bin. By dawn the mushrooms have already begun to deteriorate, the edges of their caps deliquescing into inky goo that curls, coagulates, and drips off as the entire caps disintegrate, and the mushrooms' slender stems collapse. These are among the most ephemeral of mushrooms.

Most mushrooms reproduce with spores that fall from beneath their caps, to be carried away on the wind. In contrast, the genus Coprinus has come up with the smart idea of mixing its spores into a bunch of smelly goo that sticks to the bodies of insects attracted by such stuff, and then the insects can carry the spores to new places.

Inky-caps are too small and insubstantial to think about eating. Still, I just like greeting them each morning, and I like thinking of their mycelium throughout the days and nights working its way through my compost bin, helping break down the straw, weeds and my own excreta deposited there, into a rich compost that will be recycled into future gardens.

*****

THAT WREN

Just after dawn on Tuesday morning I realized that something was missing. For several days the Carolina Wrens had been carrying bugs to their second-hatched brood of the year. I'd grown accustomed to their perpetual flying in and out of the tool room across from my computer room in the barn. Tuesday morning all was quiet, so I knew that the nestlings had left their nest. In times past I've seen that once the nest is abandoned the whole family avoids me for a week or two.

However, in mid morning I heard a beseeching peep from inside the barn's garbage can. Inside was one of the nestlings barely keeping his head above the water pooled there after recent rains (leaky roof). I could imagine the whole sequence of events: One by one the nestlings had been coaxed to fly from their nest on the high shelf in the tool room and this one had made it out of the room as far as the trashcan's rim, but he'd bungled his first landing, tipping into the can. Once his feathers were wet he couldn't fly out. The family had gone on without him.

I dried him off and set him on the barn's cement floor outside my door where for a long time he just sat looking around. After an hour or so he began peeping and hopping about. Finally, around noon one of the adults returned flying here and there and the classic Haiku by Issa came to mind:

That wren--

Looking here, looking there.

You lose something?

A plaintive peep, a sturdy reply, a flutter of wings upward, and within moments an open beak was plugged with a green grasshopper.

After a few more feedings both birds disappeared the way wrens are supposed to on the first day of fledging.

*****

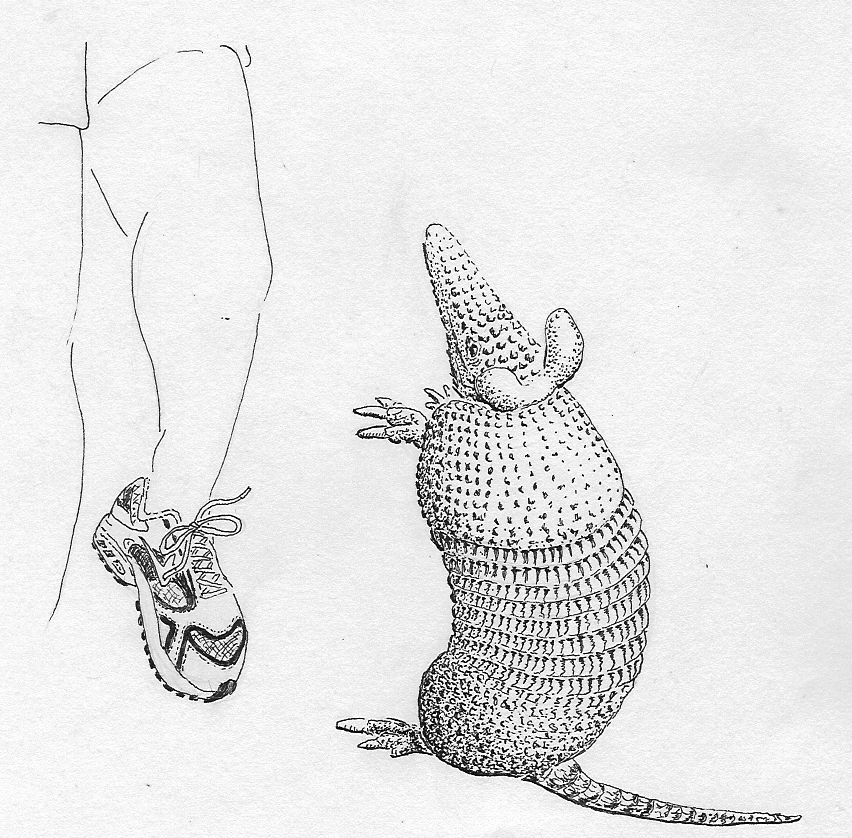

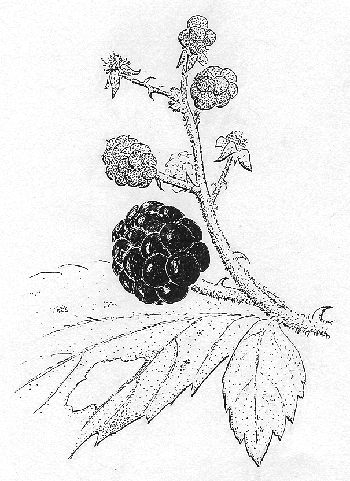

BLACKBERRY WEEK

A few ripe blackberries have been appearing here and there for a couple of weeks and they'll be turning up for another month or so, but I'd say that this week will prove to have been the best blackberry picking time of the whole year. In my April 21 Newsletter I said that the blackberry brambles with their "white blossoms surge from the woods' edge into the broomsedge field like a tide of warm, green water with white froth." Now the white froth has crystallized into red and black berries -- red being the color of unripe fruits.

If you pick in the morning when it's cool, the dew wets your feet and legs, and mosquitoes can be pretty bad. If you wait until later, the humid heat pushes down on you the way Mississippi heat does. Nonetheless, I prefer picking in the afternoon, sweat streaming down my legs, and feeling the powerful sunlight slow-baking my bones.

When you're out there you know you're alive because all your senses are being tested. The canes' stickers catch your britches legs. When you get scratched, a straight line of crimson beads of blood forsm on your wet skin. In the vacuum of the heat-stymied afternoon you hear the light thumps of berries dropping into your bucket, and the rustlings of the Cardinals upset in the briers, for the bramble is their home and they love those berries as much as you. Your hands grow purple-stained and so do your lips. Sometimes a spider or a stinkbug gets into your bucket, but you just pick it out.

Something funny always happens at the end of a good picking session. When the bucket is nearly filled, though you've been watching the harvest grow one berry at a time, suddenly you're surprised by what a mess of them you’ve picked, and how handsome and substantial they look all glossy and plump, and so black that they're almost blue.

You almost feel as if in that field you've rediscovered a subtle but powerful wisdom: That one berry at a time, if you keep at it, leads to a beautiful heap of berries.

*****

KATYDIDS GALORE

When night falls there comes into the forest a magnificent roar consisting of the calls of thousands of Katydids, Pterophylla camellifolia. The songs are loud and raucous, similar in quality to the buzz-saw drummings of the periodical cicada, except that they come in short bursts, something like "rik-rik, rik-rik, rik-rik." The wonderful thing is that usually the calls are synchronized so that the roar pulsates with a mighty rhythm. Lying beneath the mosquito net on my sleeping platform in the woods, I often discover my foot keeping beat. The pulsating roar is almost hypnotic, and I can see how certain nervous-type individuals could be driven mad by it. Fortunately, I find it restful and I am glad to experience it.

Well, I am only about 99% sure that these are Katydids. I have tried dozens of times, flashlight in hand, to spot one as it calls, but to no avail. These are tree-top singers and call only at night.

One source of my slight doubt about their identify is that what I hear now is not the same katydid call I knew during my childhood in Kentucky. Kentucky's katydids call in the same loud, buzzy manner, but up there it makes sense when people claim that katydids say their name when they call -- "Katy-did, Katy-didn't. Katy-did, Katy-didn't..." Our Mississippi katydids’ "rik-rik" call just isn’t like that.

However, I found a page on the Internet where a researcher says that "Southwestern populations call with a slow pulse rate and only one or two pulses per phrase." Natchez is considered to be in the Southwestern part of the katydid's distribution and "two pulses per phrase" is exactly right for what I hear. This specialist claims that there are at least three distinct Katydid populations, each having its own characteristic call. There are Northern, Southeastern and Southwestern populations.

Our Katydids, like those in Kentucky, call all night, beginning exactly at dusk, and ending exactly as dawn, though they tend to trail off right before dawn. There's an exquisite period of several minutes when a few katydids are calling while the Cardinals and Summer Tanagers are just awakening, mingling their peaceful mornings songs with the thinning Katydid drones.

*****

STORM PLUMS

So often the most vivid moments of one's life are compounded of two or more events taking place at the same time. That's the way it was Wednesday when I went plum picking as a storm came up.

The storm was one of those dramatic ones that rolls in from the west with plenty of thundering, and during the calmness proceeding the storm leaves on trees go limp and flip over looking silvery. On the horizon there's a solid dark sheet of blue-gray rain but, above, the rounded clouds have upward-swooping sides, like the ones Michelangelo painted with cherubs sitting on them looking down at us, their legs dangling over the clouds' edges.

I've had lots of modems get zapped so as soon as the thunder started I pulled all the plugs. Usually during storms I do odd jobs around the barn, but this storm was so spectacular that I wanted to be in the open where I could experience it like a symphonic concert. I wanted to feel the thunder rumbling through my guts, and I wanted to feel every molecule of the first chilly breezes on my overheated skin. Therefore I decided to go check on the Chickasaw Plums, Prunus angustifolia, I reported on as flowering in this year's March 7th Newsletter.

Back then I was tickled to discover "just two little, white blossoms inside an intricate tangle of spiny, dark stems." Now the thicket was lushly green with leaves, and some of the trees bore heavy crops of cherry-red, cherry-size fruits. A big rattlesnake has been hanging out around there, so very gingerly I insinuated myself among the spiny stems, as alive as I could be to the snake danger, the scratching of the spines on my bare back, shoulders and chest, and to the approaching storm, the falling rain of which now could be heard moving across the Loblolly Field.

Those glossy, red fruits hung among green leaves were as pleasing to look at as a healthy child with a smile. The very instant I picked the first plum, a big raindrop splattered on the bald spot atop my head and a kinky puff of wind dragged a spiny stem across my back and arm leaving little beads of plum-red blood.

Before long I had all the plums I could carry in my hands, and spiny plum branches lashing in the wind were flailing me. Lightening was hitting awfully close and the rain was so cold it didn't feel good. My glasses were wet and foggy so I worried about not seeing the rattler as I worked myself out of the thicket. For a while all my thoughts were rattlesnake, too-close lightening and too-cold rain.

But, I made it. I dried off and got warm again. And then I ate those plums.

*****

PLUMS OR CHERRIES?

Ripe Chickasaw Plums are so similar to average cherries that the question arises: What's the technical difference between a plum and a cherry?

One distinction is that plums have a single, shallow "furrow," a sort of crease, running from the base to the top, while cherries don't. Also, plum skin sometimes but not always possesses a whitish "bloom," while cherries don't. A few plum types have tiny hairs on them, but cherries never do.

*****

SUMMER SOLSTICE

On Friday I celebrated this year's Summer Solstice. Walking in the fields I reflected on the fact that half of the current solar cycle, the "natural year," is now completed.

Part of my celebration consisted of summoning up memories of this spring's most pleasant moments -- of spotting the year's first flowering trilliums and violets in the bayou, and of watching the first leaves come into the trees. I recollected the fun I had chronicling bird migration, and I tried to remember what the mulberry tree looked like that day I saw so many Cedar Waxwings in it. I tried to recall the exact warble the Painted Bunting made that morning I found him in the orchard. I remembered the morning I walked into the garden and saw the first beans coming up, and in my mind I replayed the view of the blackberry field white with blossoms. I even tried to reconstitute on my tongue the taste of the year's first ripe tomato, and that wasn't so long ago.

Now our days will begin growing shorter and before the month is out probably I'll be feeling "fallish" again.

In fact, it seems that I have come to recognize only two real seasons, spring and fall, plus I admit that there are brief periods in between these seasons when "Nature holds her breath." Nature "exhales" spring with all its blossomings, hatchings, openings-up, avalanchings-forth and lightings- and warmings-up, then "inhales" fall with its fruitings, fallings, crystallizations, wrappings-up, buryings, darkenings and coolings-off.

Another part of this week's Solstice celebration was a kind of prayer formulated as I walked across a sunny field. The prayer consisted of consciously recognizing that I was glad for being able to walk as I was, and to think the thoughts I am reporting here. I never ask anything in prayers, just give thanks, but if I had been the kind to ask for something I think I would have appealed to the Creator for things to keep on happening as they may, and I would have asked to remain alert beneath the sky, and to be able to see and feel as much of everything as I can.

After the walk I passed by the garden. I carried a big piece of cornbread in my pocket so I sliced that open, picked some ripe cherry tomatoes, sliced them and spread them atop the cornbread, plucked a handful of basil leaves, shred them and strewed them atop the tomatoes, then I dug up a garlic bulb, sliced it, and spread the slices atop the basil, and that garlic was so juicy that it sparkled in the sunlight. Then I ate it all, and it was good, and looking up into the blue sky as I chewed I felt something like a deep sob coming on, but then somehow it ended with a chuckle, and I still can't say exactly what that was all about.

Maybe it meant that I'd had a good celebration.

*****

JUST HOLDING

Between Nature's exhaled spring and inhaled fall there's a brief moment of "just holding," which is neither spring nor fall. That's the time we're experiencing right now. Besides being graced with the Solstice, the "just holding" time has its own character worth noticing and thinking about.

Mainly, this is exactly the time to feel nature humming along at top efficiency. When we're not distracted by the rush of either spring or fall, with our internal ear we can sometimes hear the majestic humming, the "ommmmmmmmmmmmmm...." Nature makes when she is just busy being herself. You hear this best in mid-afternoon when the field is quiet and the sunlight and heat stun you with their power. "Ommmmmmmmmmmmmm..." maybe with a solitary meadow grasshopper stridulating its bzzzzzz-zip-zip-zip-zip-bzzzzzzz in attendance.

One way to sense the efficiency of nature's work at this in-between season is to step from the forest into a sunlit field in the afternoon. The forest is cool but the sunlight in the field beats down with unexpected harshness. The temperature difference you feel as you pass from the forest into the field represents the energy the forest is using but, in the field, is being lost to the ecosystem when it hits your skin. This is energy that could have fueled photosynthesis, and thus could have been stored among the atomic bonds of the trees' carbohydrate molecules, and, later, when the trees die and decay, might have been shared with the rest of the ecosystem, thus fueling untold corners and levels of life.

When I returned to the garden I wanted to sit in the remains of an old, metal lawn chair I'd retrieved from a junk heap. The chair was painted the same green hue as the leaves of the bean vine twining on the giant-bamboo trellis next to me. When I sat on the chair, because it had been in the sunlight, it was so hot that I had to jump back up. Then standing there I reached over and touched the bean leaves. They were cool and pleasant to the touch, despite being in the same sunlight as the chair.

I stood there a long time thinking about this difference between a forest and a manmade open area, and a green plant and a green chair, and in my Solstice mood you can imagine the conclusions I drew.

*****

SHOWERING AT THE COMPUTER

Being a hermit in a tiny, hangdog trailer in the woods has its compensations. I benefited from one as I typed the above entry.

I've told you about the perpetual pool of water atop my trailer where the roof sags. In the center of this roof there's a small, square, screened window that can be screwed open from below. During the summer the window stays open most of the time, to let out the heat. In the hottest part of each afternoon birds come to bathe in the pool. As they flutter they send an occasional cool, refreshing spray through the window onto my sweating shoulders below.

It's a system no one could have dreamed up intentionally, yet it works pretty well.

*****

DAYLILIES AND FRIED CHICKEN

I have a vivid recollection from around 1952 of being a kid on a hot summer day in rural western Kentucky, in the back of our old, black, running-boarded Chevrolet rumbling down a one-lane, weed-choked gravel road, hot air pouring through the windows, my parents up front, us going to visit my Aunt Hazel who lived at the end of the road. Already I imagined I could smell her fried chicken, greasy fried potatoes, green beans dripping with pig grease, crusty biscuits, and all the peeled, thick-sliced, white-salted red tomatoes we wanted. Right before arriving at her house the roadside weeds stepped back a little to give way to a spectacular colony of Common Orange Daylilies, Hemerocallis fulva.

I remember thinking that those flowers were nearly as pretty as a Redcedar decked out for Christmas. Half a century later I can't see the orange-yellow hue in any context without associating it with daylilies and Aunt Hazel's fried chicken and fried potatoes.

Daylilies are flowering now along area ditches. There's a colony at the bend in the highway, then several individuals scattered here and there farther along the road. I imagine that one day a house stood at the bend and those daylilies were treasured ornaments, but now the county graders come along digging into the original colony and spreading tubers up and down the right-of-way. I suppose the daylily is happy to have its tubers dispersed, but this seems harsh treatment for such a dignified species, an exotic one with origins in the Orient.

The daylilies along our road are double-flowered, and I find that a little disappointing. I prefer the classic blossom in which the flower parts are all distinct, as they evolved in nature. In these double flowers the extra corolla lobes are derived from stamens (the male parts). Looking closely at the blossom you can find instances of half-formed petals with anthers fused into their faces.

These are monstrosities that wouldn't be tolerated in wild nature. Double-flowered varieties exist strictly because of man's taste for gaudy color, without regard for the beauties associated with simplicity of form, functionality of parts, and naturalness of aspect. But mindless splashiness is the taste of the times.

I know I'm in the minority on this. I've seen the fuss made on the US National Arboretum's "Award Winning Daylilies" Web page featuring 19 award-winning, double-flowered daylily cultivars with names like Pojo, Prester John and Peach Souffle.

When I see the extravagant blossoms featured at that site I feel like a fat kid surrounded by too much sweet stuff. I think how glad I'd be to just sit awhile among the old-time Common Orange Daylilies along Aunt Hazel's weedy gravel road.

*****

ADOLESCENT BIRDS

This week several bird families around my trailer have been experiencing the "teenager" phase of life. Sometimes it's been funny, sometimes it's been hard to watch.

A family of White-eyed Vireos in the blackberry field was the Ozzie & Harriet of the neighborhood. The neat-looking little parent quietly flitted from stem to stem gathering bugs among the berries while three well-mannered fledglings orbited about gawking and, when the parent found something, quivering their wings to look pitiful so they might be fed.

The Pileated Woodpecker family was more like real life. Flying into the top of the big Pecan tree, it looked like a single mom with a clumsy, big-boned brat in tow. The young bird's body language spoke an ongoing monologue:

"There she goes again, all she can think about is banging her head against trees, boring, boring, boring, how disgusting... but, LOOK, what a big grub! Gimme gimme gimme GULP! Wellllll... I deserved that. So there she goes again, another tree, another banging, just can't enjoy life, same old thing, well, guess I have to tag along, what a drag!"

I witnessed a heart-wrenching crises among the family of Cardinals whose territory centers around my trailer. There were three almost-grown kids, two females and a male, and one late afternoon the father apparently decided that the male kid had to go. The father attacked the young male and the kid was obviously shattered. When adult males fight over territories they position themselves on opposite sides of the imaginary territorial line, they glare at one another and skirmish until one flies off.

But here the young male was inside his family's territory and he didn't know where to go. When the father chased him, he flew in circles or figure 8s round and round inside the only home area he had ever known. Finally in exhaustion he landed on a Hophornbeam's lower branch, but the father went right at him, nabbed the top of his head in his beak and rode the kid to the ground where they both flapped and the kid screamed. Even with my human ears I could hear in the young bird's call a profound sense of feeling betrayed. It was much more than a "Stop, you're hurting me!" tone, there was a clear "I thought I was your son!" sound, and it was heartbreaking to hear.

As dusk closed in and the two young females huddled wide-eyed in shadows watching the conflict escalate to another confrontation at last the young bird stopped flying in circles and figure 8s, suddenly rose higher into the air and in a straight line flew across the blackberry field into unknown territory, not to return.

*****

IGNORANCE BEGATS VIOLENCE

In the shadows beneath Black Willows at the edge of a pond dug for the deer deep in the forest I came upon a poisonous Western Cottonmouth, or Water Moccasin snake, Agkistrodon piscivorus leucostoma. It lay with its head resting atop a coil of its own thick, black body.

Usually I wouldn't have paid much attention but I could see that this particular snake was extremely dangerous. That's because he was about to molt. When a snake's molting time draws near, its outer skin starts separating from its new, inner one. The skin over the eyes also is molted, and there's a brief period when air gets between the old eye covering and the new one, causing the space to turn white.

My cottonmouth's eyes were completely white because of this problem. He was practically blind.

The snake tensed, turning his head all around, but obviously he was unable to see where I was. Then suddenly like a spring being released, his coiled body shot into the air and there was a flash of whiteness as he stabbed where he thought I might be. Again and again he sprang, the white discharge of his open mouth for half a second vivid in the gloomy light.

I moved away thinking the snake might be overdoing it a bit. I'd never seen a serpent attack with such ferocity. But then I'd never seen a snake whose lenses were so completely opaque just before shedding.

Maybe it's a law of nature that the less information you have, the more vulnerable you are, and therefore the more aggressive and violent you must be to stay alive. It's almost as if the snake were telling us that if we wish to reduce violence in our human society, we would do best to invest our monies in schools.