LISTENING TO SPRING ODORS

Here and there in our woods, especially on moist, shaded banks, bright yellow blossoms adorn slender branches of the Spicebush, Lindera benzoin. This is one of our most spectacular harbingers of spring. If with a thumbnail you bruise a Spicebush's slender stem, a spicy, clean-smelling fragrance blossoms into the chilly air. This week the Spicebush's smell got me to thinking about odors.

In traditional Japanese culture there's a ceremony called "Listening to Incense." The idea is to refine one's sense of smell and to exercise the ability to respond to odors of various incenses. I have read of one such ceremony during which the participants not only identified a large number of discreet fragrances and combination of fragrances, but also related the odors to specific events in ancient Japanese history and mythology.

When it's cold, things don't smell much, but heat and humidity nurture odors. During this spring's warmer, moister days, the sleeping bag in which I've slept all through the cold weeks has begun emanating a certain funky odor, as does the sweater and socktop I've worn a long time.

I don't hesitate to speak of this, though I know that in our culture we are programmed to be uncomfortable and unaccepting of nearly all odors that are not sweet or commonly accepted by everyone as "wholesome." I believe that the degree to which most people in our culture are antiseptic, scrubbed and odorless, or even artificially perfumed, amounts to nothing less than an unhealthy obsessive neurosis.

Lately I've awakened several times deep in the night and I've made a point of just lying there cocooning in my sleeping bag, savoring odors blossoming up from the bag and of odors carried on the wet, velvety night air. I've been amazed at the richness of the experience.

There was the odor of mud, woodsmoke, crushed grass, wet feathers, Yellow Jessamine, my own oily skin, moist wool... There were cheesy, moldy, musty, musky, overripe odors -- purple, brownish-green and bruised-blue ones -- odors in minor keys, base-note odors and odors that neither laughed nor sneered but just came curling about like a sulky friend inviting attention.

You might want to try it. Unhitch your preconceptions and prejudices, close your eyes, turn off your ears, lie quietly, and just smell. Give a name to each odor that comes along, put it in a mental pigeonhole, then go to the next one. Quietly collect odors until you have a rainbow, then let yourself be drawn into your rainbow, experience it like walking in a flower garden, loving the dark blossoms as much as the bright.

*****

17° AT DAWN

Thursday morning at dawn it was 17°F (-8.3°C). I jogged eastward into a kind of sunrise seldom seen at these latitudes. It looked like a slab of inflamed raw flesh lying on the horizon. The dark blue sky lay right next to it, with no pastels between the hard colors to mediate. It looked spooky and I was comforted by the white steam billowing from my mouth, something alive and normal. Wiping my mouth with the back of my hand I felt chunks of ice coagulating in my beard. When sunlight began casting golden halos around the dangling beards of Spanish moss along my path, finally things began seeming normal.

My main task for the plantation this week has been to grub out with a shovel deep-taprooted Honeylocust trees in one of the hay fields. Honeylocusts bear large, hard spines that can puncture a tractor tire or go right through a shoe. So at midday on Thursday in the middle of the field I ate my cornbread and then did something that most of the time is impossible here: In the cold, sunny air I lay in the grass on my back, looking into that curious blue sky. Usually lying in the grass is impossible here without ticks, fireants and chiggers swarming over you.

How seldom we lie on our backs on the solid Earth, yet what a comfort it is! My body tingled from the morning's exertions, and now the dazzling sunlight stung my skin. Red blotches and white starlets animated the blackness behind my closed eyelids. The cold but sunlight-charmed air hummed with silence.

But then a grasshopper flew by, it's crackling sound arcing from one side of my head to the other.

Well, if that grasshopper could make such a lusty crackling after a 17° dawn, probably the ticks, fireants and chiggers were just as capable of doing their thing, so that was the end of my Earth-lying.

*****

CHICKASAW PLUMS FLOWERING

Last Monday, on March 1st, the first blossoms of our Chickasaw Plums, Prunus angustifolia, appeared. It was just two little, white blossoms inside an intricate tangle of spiny, dark stems, but what a pleasure it was to walk up to them, stick my nose next to them, and breathe in their perfume. What odor could be more pleasing than that of wild plum blossoms on a spring morning when the air is warm, moist, and redolent of mud and crushed grass?

This species' flowers appear before its leaves. Sometime during the next couple of weeks, probably for just one or two days -- until a stiff breeze comes along -- our thicket of Chickasaw Plums will simply glow with white flowers, and if you go stand among them the perfume will throw you for a loop.

Chickasaw Plums are native throughout most of the southeastern quarter of the US, averaging maybe 10 feet tall, and bearing blossoms a bit smaller than those on cultivated plum trees -- only about 0.3 inch across. On this property they form a thicket about 20 feet long and 10 feet broad, along a fence. I'll bet that the thicket’s parent tree was "planted" there by a bird who years ago upchucked a plum pit while perched on the fence's wire. Since I first noticed the blossoms as I was pulling up metal fenceposts from inside the thicket, I can also tell you that their interlocking branches bear slender, sharp-pointed items that are half twig and half spine, but which can puncture and scrape as if they were 100% spine.

Around the end of May these trees will produce bright red or yellow, lustrous, thin-skinned, juicy and a bit tart fruits about half an inch in diameter. Last fall, right after the trees lost their leaves, I dug up several sprouts, making sure to get plenty of their underground runners. Now the buds on those transplants are opening and I hope that this time next year we'll have the beginnings of several more plum thickets.

*****

BROWN THRASHERS SINGING

In last year's October 13 Newsletter I described a "wave" of Brown Thrashers passing through migrating southward. I remarked how secretive they were, hiding themselves in bushes and issuing melancholy smacking sounds. All winter some have hung around, always skulking and staying quiet, sometimes showing a yellow eye glaring at me from deep in the shadows. Then one day last week and several days this week, the Brown Thrashers have begun singing. It's not half-hearted stuff, either. They fly into the tops of the taller trees and call louder than anyone else except the hawks and owls. Whole mornings they sing.

I've been thinking what it must be like being a Brown Thrasher at this time of year. Naturally these behavioral changes are brought about by alterations in their hormone levels. Yet, surely, for birds as well as with us, hormones express themselves as moods.

So, what must have been the mood like that all winter kept the Brown Thrasher silent and withdrawn? What conflict of urges have these poor birds endured these recent days as their minds lay locked in gloomy hush while their hearts irrepressibly began swelling with the need to fly high and sing? What must it be like now there in the top of the big Water Oaks singing with nothing but the sky above and the broad Earth spread out below, when just a day or two ago it was enough to lurk inside dismal Blackberry thickets?

*****

SONG SPIRIT

Back to those singing Brown Thrashers...

Biologists are trained to avoid being anthropomorphic when interpreting animal behavior -- they don't assume that ducklings follow their mothers because they love them. I believe in that admonition, but I fear that in our culture we have gone too far with it, and this reduces our sensitivity to, and appreciation for, other living things.

The Brown Thrasher at his appointed time overcoming his wintry sulk, then flying to the tallest treetop to sing his loudest and clearest, has this week been what I think of as a local outburst of the Creator's spirit. Each morning when I passed that singing bird I tipped my hat in form of a silent prayer.

For, I believe that the Creator's spirit flows everywhere, and we -- we humans and birds and everything else -- are part of it, the way that notes are part of music. The Creator's spirit wrought something out of nothing, crafted unfathomable beauty and complexity out of chaos, and right now evolves the Universe and all things in it to ever higher levels of sophistication, and ever more exquisite manners of being and conceiving.

So, I think I know that bird's feeling, though I try to avoid anthropomorphism, and I know for sure that the bird's brain is wired much differently from my own. I know the thrasher's feeling because each of us is part of the same general flow of the Creator's spirit flooding through the Universe.

The bird doesn't sing because he's happy in a human way, but I am confident that he is indeed tickled through and through by the Creator's springtime spirit flowing through him, just like me.

*****

BLACKBERRY BRAMBLE GREEN DIFFUSION

In abandoned fields, around old brushpiles and at the edge of woods, often there are blackberry brambles. Stiff, semi-woody, gloriously spiny, close-together canes six feet long and longer arch from the ground forming thickets a human or even a deer can't get through, but which a rabbit can, at least by keeping his ears low. Now those canes are issuing penny-size tufts of green leaves. When seen from a fair distance these tufts give the entire bramble a diffuse, pale green cast. This is a wonderful sign of spring.

If you stand close enough to see individual tufts and there's a low sun beyond the bramble, the tufts glow and seem suspended within a dark mahogany cloud. If you stand farther away and let your eyes drift out of focus, the brambles look like glowing, green fog. Before long this blackberry bramble green diffusion will seep into the trees as buds on tree limbs burst with little leaves.

*****

SOUTHERN TWAYBLADE ORCHID

In the October 28 Newsletter I told you about a dainty little orchid about half a foot tall blossoming here, but so slender and small-flowered that most people never notice it. It was the Nodding Ladies' Tresses. Last Sunday in the woods I found a second similar orchid species that was the same size and just as slender and small-flowered. It was the Southern Twayblade, Listera australis. It seemed impossibly delicate to have survived that week's 17° weather, but obviously it had.

The similarities between the two species are only superficial. Getting onto my hands and knees and looking with a handlens, the tiny (3/16 inch long), reddish-purple flowers displayed profoundly different floral anatomies. Well, this is how orchids are: At first glance they're all alike, but up close every blossom type is a wildly imaginative variation on the fundamental orchid theme.

This is a fairly rare wildflower. In fact, though I looked for a long time, I found only one specimen in that part of the forest.

*****

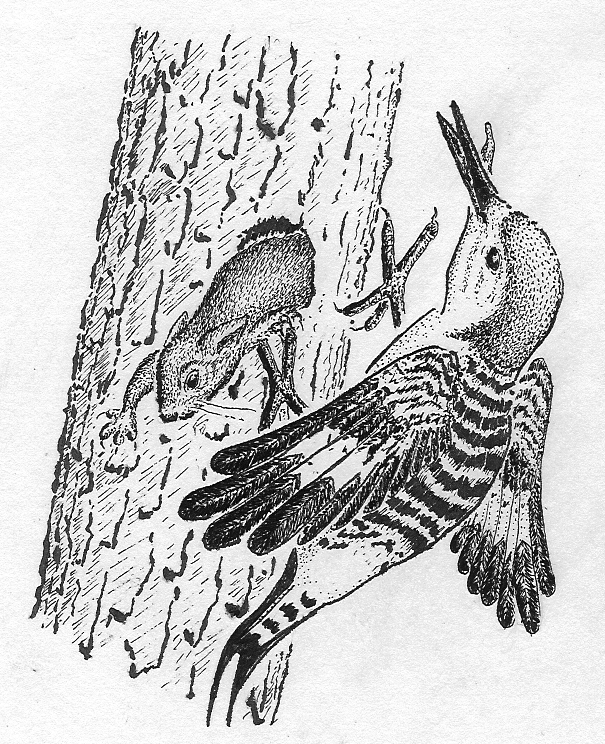

WOODPECKER MEETS FLYING SQUIRREL

Next to a pond where I was sitting, a Red-bellied Woodpecker was pecking at something inside a hole in a dead snag about 30 feet up a Water Oak. I thought he might be cleaning out the hole to make a nest, but he wasn't removing debris so I couldn't figure out what he was doing. And then it became clear.

Suddenly his wings flashed and he jumped back as a Southern Flying Squirrel, Glaucomys volans, shot from the hole and scrambled down the trunk with the quickness of a mouse streaking across a floor. He moved so fast that I hardly saw more than his size and color, and a goodly amount of loose skin rippling along his sides.

Within a second or two the squirrel had disappeared. The woodpecker hung around for a minute and then flew off not to return while I was watching. My impression was that getting the squirrel out of the hole had been his whole mission, and I can only guess that he simply didn't want any potential woodpecker nesting hole in his home range claimed by anyone, whether another woodpecker or a rodent.

Because Flying squirrels are nocturnal, I never see them unless one of them has bad luck. In towns, cats often bring them in. At my previous location they lived inside the walls of an old building and at night orchestrated a wonderful noise. The people there occasionally managed to trap one, but always others remained to thump and scrape all through the night. Here on summer nights I often hear sounds in the trees which I suppose to be made by them, especially at acorn-eating time.

******

MUD TURTLES IN THE WOODLAND POND

Around here if you see a turtle in a typical farm pond, usually it's the Red-eared Turtle, the kind sold in pet stores, with yellow stripes along its head and neck, and bright red spots where its ears might be. Sometimes it'll be a snapping turtle. In fact, around here, anytime you spot a turtle that's not a Red-eared or a snapper, you have something interesting.

Our little woodland pond has Mud Turtles, Kinosternon subrubrum, and lately they've been sunning themselves on logs. Mud Turtles are found throughout the Southeast, and if there's anything special about their general appearance it's that their top shells, their carapaces, are higher than most pond turtles, though not as high as a dry-land box turtle's. Mud Turtles are smallish, with their shells seldom more than 4 inches long. Otherwise Mud Turtles are fairly unspectacular, being olive to dark brown, with little ornamentation other than some yellow around the shell's sides, and some vague, yellowish speckles on the head.

Mud Turtles eat crayfish, insects, mollusks, amphibians, aquatic vegetation and other things as they walk along the bottom of a pond, swamp or stream. Their main enemies are raccoons, crows and humans.

Mud Turtles are represented by three subspecies and my fieldguides indicate that here we should have the one known as the Mississippi Mud Turtle, K. s. hippocrepis, with yellow stripes along the head. However, ours are clearly the Eastern subspecies, K. s. subrubrum, so someone needs to tell the fieldguide writers about that.

*****

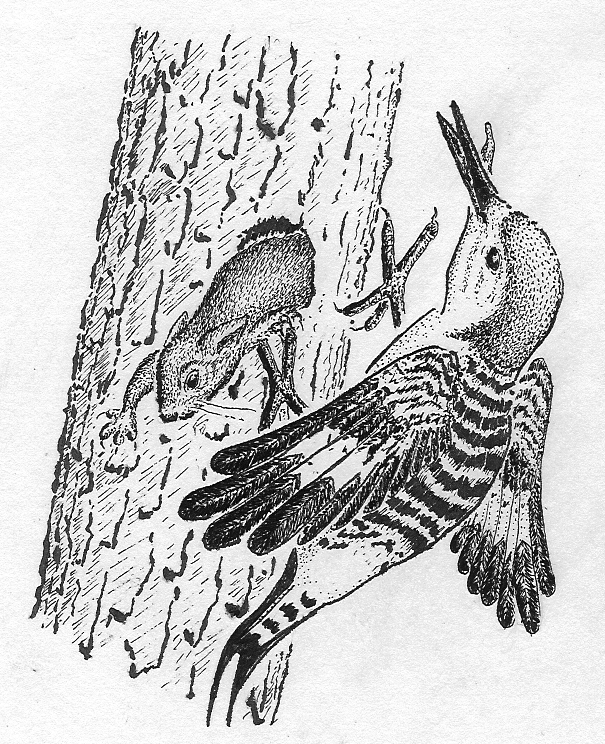

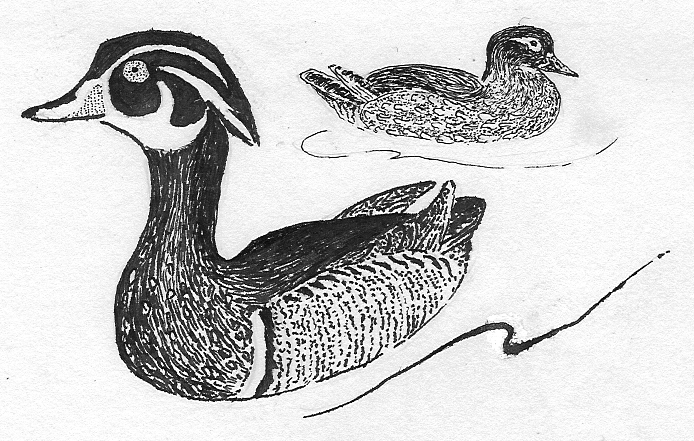

WOOD DUCKS

During Friday's walk one highlight was coming upon a flock of eight Wild Turkey hens in the woods. However, the best moment of all came when I was resting beside the woodland pond and suddenly male and female Wood Ducks descended through the trees and landed right in the pond's middle not 20 feet from me. Prepared for just such a happening, already I held my binoculars near my face, with my elbows on my knees. Very slowly I brought the binoculars up, and then for about 20 minutes I was able to watch the birds without my arms getting tired holding up the binoculars.

Though I remained perfectly still, an awareness seemed to grow in both birds that something about my presence wasn't right. They stared and stared right at me. After about five minutes the male began preening, though the female never did. The male nervously watched me as he curved his neck, swam through shadows and sunbeams, sloshed water and stretched his wings and legs, displaying his prettiness like a model on a stage.

The greenness of his crown shimmered with iridescence. The satiny blackness on his cheeks was outlined exquisitely by fingers of snowy whiteness, and in the center of this excellent harlequiny sat his blood-red eye, always focused right on me. His warm, deep-chestnut-colored breast when seen in sunlight revealed itself as finely speckled, like a knight's coat of mail. And all this, as well as other colors and designs too numerous to list, were reflected in the pond's black water. What a display!

Though I never moved a hair, gradually in both ducks the conviction seemed to gather that I was more than an inert bump. The male began opening and closing his beak as if quacking. I could hear nothing, but surely the female could. Then the male swam to the pond's bank and climbed upslope a few feet, constantly keeping me in view, and the female followed. This better view unsettled them even more. Maybe you recall how last year I enjoyed a similar experience watching a Pileated Woodpecker, who just never caught on that I was something special. These ducks, I believe, were smarter. Something in their brains was perking, enabling them to interpret images at a higher level than is possible for a simple, grub-gulping woodpecker.

Both birds then positioned their bodies behind different trees, with their heads poked around from behind, looking squarely at me. I didn't move. But finally their concern crystallized, and both rose into the air and flew away.

*****

WOODSIAS EMERGING

On the steep, mossy slopes of gullies eroding into our forested uplands, right now there's a delicate little fern unfurling. It's the Blunt-lobed Woodsia, Woodsia obtusa, sometimes called Blunt-lobed Cliff-fern.

It's unfurling in the usual fern way, with "fiddleheads" uncoiling from base to tip, like one of those curled-up paper things kids blow on at parties, and shaped like the knobby head of a fiddle. Christmas Fern fiddleheads are also uncoiling right now, but they're much larger. Deer love to eat Christmas Fern fiddleheads, which can be boiled and eaten like asparagus, but the Woodsia's fiddleheads are far too small to bother with. The mature Woodsia frond stands only about 6 inches high.

The nice thing about these Woodsias is that they look so perfectly at home where they are. Their little yellow-green fronds are among the most fragile-looking and frilly of all ferns, and somehow their delicate appearance matches perfectly the environments in which they grow. They unfurl on slopes encrusted with green tussocks of soft moss and threads and ribbons of scrambling liverworts. Here and there a slug's glistening slime-trail crosses the greenness like a fairy's trail through an enchanted woods. Simply sitting and gazing at this peaceful community fills one with admiration and peace.

*****

DIETER'S GARDEN

Back to those Woodsias. On the day I hiked through the woods after admiring the Woodsias I experienced this train of recollections and thoughts:

The notion that the Woodsias had looked "so perfectly at home where they are" took me back to my early traveling days, to a delicious summer morning in Vienna, Austria in the 1970s, when I was visiting my friend Dieter. We were in the vast gardens of the old Summer Palace of Schönbrunn, where I had never seen so many roses, row after row of them, and so many perfectly trimmed hedges, and acres of geometrically arranged beds of tulips and irises and other bright blossoms.

"I never dreamed a place could be so pretty," I gushed to Dieter.

Dieter, one of the most dignified and refined individuals I've ever met, glanced at me with pity in his eyes. Art history was a passion with him, and the matter of the beauty of Schönbrunn's gardens rightly fell within his domain.

"You can think about it in evolutionary terms," he said, more or less. "Maria Teresa laid out the garden's plans in the early 1700s. Just a few years before that, there'd been a real question as to whether Vienna could survive the starvation brought on by a siege mounted by the Turks. In a real way, then, glittery, ostentatious Schönbrunn with its regimented flowerbeds and eternally clipped hedges can be seen as a reaction to those anarchic earlier times, a statement asserting Western man's newly acquired dominance over his often-hostile environment."

"These gardens are bright and totally controlled like an infant's playroom," Dieter continued. "There's an obsession here with bright color, ignoring more complex possibilities such as the mingling of leaf textures or the interplay of form and shadows. There's a single-minded fixation on simple geometric precision while ignoring harmony with the landscape, for example, and local folk traditions. This garden is an effort by Maria Teresa and the people of her time to convince themselves that with militarism and science they could overcome what they regarded as the chaos of nature. When I walk in these gardens, yes, the bright colors are nice the way children's bright balloons are nice, but, on a higher level, I am oppressed by the garden design's total lack of mature spontaneity, and by its insensitivity to its natural and cultural context. It's almost as bad as your mowed lawns in America where aesthetics among the masses also remains at an immature stage of development... "

The shock of having such a fully formed thought pregnant with so many alien assumptions placed before me left me speechless. Instantly I recognized veins of truth in his argument. All I could do was to sniff a rose and grin.

In later years I learned how plantings could be arranged so that, for instance, gatherings of leaves complemented certain blossoms. There have even been times when I also felt oppressed by naked, straight lines of tulips marching across mowed American lawns, no matter how bright the tulips' reds and yellows were.

But, now in my graybeard days, somehow I feel as if I've wandered through and then out of the whole discussion, and when I see a tulip wherever it is I just feel like dropping to my knees and poking my nose into its brightness.

Still, I'd like to visit Dieter again, to see how his ideas have evolved. I'm sure that, as always, his insights will have developed beyond mine. I would like to broach with him this idea:

From what I've seen, the most sophisticated gardens are those aspiring to look natural. Therefore, might not the final stage of aesthetic development be when one loves best what is indeed natural -- the wild forest, the marsh, the meadow?

I would like to ask Dieter if any garden he can imagine could equal the loveliness of the embankment I visited this week, where the native Blunt-lobed Woodsias unfurled so graciously among their homey little moss and liverwort companions.

*****

WEEK OF THE BIG CHANGE

During the whole year there will not be a week during which the forest's appearance alters more than during this last one. A week ago the forest was gray and brown but now it is definitely green as leaves burst from buds. Many trees are flowering. Blossoms of Redbuds and Dogwoods explode at woods' edges, and along streams Cottonwoods drop finger-sized, wormlike, red catkins. Plum trees look like large bouquets of white blossoms with black stems, and the oaks issue millions of honey-colored catkins of male flowers. Pawpaw trees bear their curious three-symmetry brown blossoms and in the forest's understory Red Buckeyes surprise the eye with luscious yellow-green leaves and spectacular clusters of red blossoms.

Wisteria vines are heavy with drooping, lavender flower clusters you can smell from a hundred feet away. Saturday at dawn as sunlight-dazzle melted frost from green grass and charmed the icy blue air, imagine how those Wisterias smelled, with a hint of plum-blossom from down the road. Smelling this, with the eye on flaming azaleas along the drive, a hermit on his bicycle laughs and just peddles on through the orchard's steaming wet grass, which has its own odors, textures and meanings.

*****

POKE WEEK

Also this is the week when poke sprouts got big enough to eat. A well prepared dish of poke is as good as any plate of asparagus and in some ways better. Poke-picking time has always been important to my Kentucky family. When my mother was alive every year at this time she, my grandmother and I would pile into the old Chevy and drive miles to certain spots we knew about, where poke grew in profusion. Poke sprouts emerge from large, underground roots, and you pick them when they are up to a foot tall. You can cook them like asparagus or -- even better -- pickle them. What a wonderful thing is pickled poke on a mid-winter fried-egg sandwich!

Poke is known botanically as Pokeweed, Phytolacca americana. It's such a strange and peculiar plant that it has it's own family, the Pokeweed Family, or Phytolaccaceae.

The best place to find Pokeweed is where somebody has bulldozed a pile of trees. Pokeweeds like recently disturbed, rich soil, open to the full sun. You locate plants by spotting last year's white stems, now bent to the ground as if they had melted. Stems of Giant Ragweed also are white and in similar places, but those stems are more slender and straight. You pick only green pokeweed sprouts, for when the stem's skin turns purple and tough, it's poisonous.

I seldom pick poke here because it's relatively uncommon around Natchez. I'd rather just let it grow unmolested. However, if this week I had been back in Kentucky in some of my old picking grounds, and if I had had a way to can it, I'd have picked several bushels, and I'd have a pot of it cooked up right now!

*****

BLUEBIRDS ON MY BLUEBIRD BOX

In this year's February 29th Newsletter I told you about my building a bluebird box. The day I nailed that box onto its pole down at the Field Pond, a certain unnerving thought came to mind. That is, of the approximately 392 bird species recorded as occurring in Mississippi, how can I presume that just one of those species, the Eastern Bluebird, will choose this nest box?

Therefore, this week when one dusk I went to sit beside the Field Pond I was astonished to see a male Eastern Bluebird atop my creation, singing his heart out. He'd fly to the hole and disappear into the box's darkness, then reappear with his face framed by my jaggedly cut hole, then fly back to the top and sing some more, then return into the box, and he did this again and again, as if trying to convince himself that the box really worked. This inspired me to build a second nest box. Within two days it also had a male atop it behaving in the same manner.

The answer to the question of how my box was finally chosen by a bluebird and not another species lies in the fact that each living thing lives its life occupying a narrow ecological niche. In the big tree outside my window Black-and-white Warblers glean the tree's bark, Red-eyed Vireos keep to the higher branches, and Carolina Chickadees prefer the lower branches. Nature is highly ordered, and invisible and inviolable boundaries crisscross everything we see.

I suspect that a chickadee or wren would have loved living in my nest box, but I placed it too far from the forest and too much in open air for them. That box needed a bird loving open fields, but a bird thinking in terms of hollow snags or tree trunks for a nest site, and it needed a bird able to fit through its 1.5-inch hole. Of the 392 Mississippi bird species I know of, only the Eastern Bluebird fits all those criteria. My banged-together nest box is practically a job description for the Eastern Bluebird.

A neighbor built a nest box just like mine, and bluebirds came to check it out, but they rejected it. Probably that happened because, instead of placing the box near a large field, he put it near his house where he could see it. Bluebirds need plenty of field space to forage in, so if you don't have that, don't count on getting bluebirds.

*****

SLEEPING BENEATH THE STARS

This Monday I set up my mosquito net and moved my sleeping bag to the wooden platform in the woods. In years past I'd not slept there this early in the season. During the summer, tree leaves completely blot out the sky but, now, though most forest trees are leafing out, stars still show through the late-leafing Pecans' branches above my platform.

I had forgotten how beautiful it is to lie beneath the stars. With my feet toward the south, Orion stood to my right, the Big Dipper to my left, and right above me Jupiter shined like a coon hunter coming through the woods with a powerful beam.

It was good breathing the night's cool, fresh air. In the trailer, air pools in the night and it gets stuffy. There in the woods every breath seems to seep deep inside, energizing and cleaning away cold-weather sluggishness. I wondered how much some people would pay to experience what I was feeling -- though just about anyone can sleep outside, anytime they really want to, for free.

But, at 3:30 Wednesday morning I was reminded why some might not pay much to sleep outside. I was awakened when energizing, cleansing rain came pouring through my mosquito net!

*****

BROWN-HEADED COWBIRD MORALITY

Thursday morning as I prepared my campfire breakfast, four blackish, dumpy-looking birds landed in the top of a nearby Pecan tree. They made squeaky, gurgling calls and fluttered in a curious way so that even without binoculars I knew I had four Brown-headed Cowbirds.

I watched as three males orbited around a female displaying. During the "Bill-Tilt Display" a male would lift his head and point his bill skyward. This would often be followed by the "Topple-Over Display," during which the bird would fluff his body feathers, arch his neck, spread his tail and wings, and lurch forward, sometimes issuing the gurgling song. Apparently these displays excite females, and probably females mate with males doing the best job.

Female cowbirds do not lay eggs in their own nests. Being careful to go unobserved, sneaking quietly through undergrowth or among dense leaves, they look for the nests of birds of other species. Often they locate nests still under construction, then watch the nest until egg laying begins. Then one dawn she sneaks in, removes and sometimes eats the nest-owner's egg, and lays her own. If only one "host" egg is present, she does not remove it, apparently because doing so might clue the nest owner that something is amiss, and the nest might be abandoned.

Not only do cowbird eggs usually hatch one day ahead of the host's eggs, but also cowbird nestlings typically are larger, are more aggressive in begging for food, and grow faster than the host's own young. Even when the cowbird fledgling grows much larger than the host mother herself, the mother just doesn't catch on that there's a problem.

Of course this is hard on "host" families. Before humans began cutting up the landscape, cowbird "nest parasitism" wasn't as important as it is now because cowbirds in most places tend to focus their activities in open areas and forest edges. However, now humans have broken vast forests into tiny plots and there are so many access roads that many remaining forests consist of nothing but "ecological edges." Cowbird nest parasitism is a very serious problem contributing to the ongoing collapse of many bird populations. Species hurt particularly hard include the Song Sparrow, Chipping Sparrow, Eastern Phoebe, and Northern Cardinal.

How can Mother Nature tolerate such a free-loading species?

Maybe we just have to recognize that Nature rejoices over diversity but doesn't really care much whether individuals like you and me get exactly what we want. Nature exults in the robust feeling embodied in the music, not in the destinies of us individual notes comprising the score.