. The Newsletters are among the tree's fruits of the Nature-study process.

. The Newsletters are among the tree's fruits of the Nature-study process.

This is a living tree of thought, feeling and intuition, begun in 2020 and is still being changed. You're reading the

The tree's roots section states assumptions on which everything written here is based. The trunk describes how the meditative Nature-study process works. Arising from the trunk, theme-setting branches sprout twigs, which variously develop their branch's theme. Most twigs are accompanied by one or more entries from Jim Conrad's Naturalist Newsletters, indicated below with a  . The Newsletters are among the tree's fruits of the Nature-study process.

. The Newsletters are among the tree's fruits of the Nature-study process.

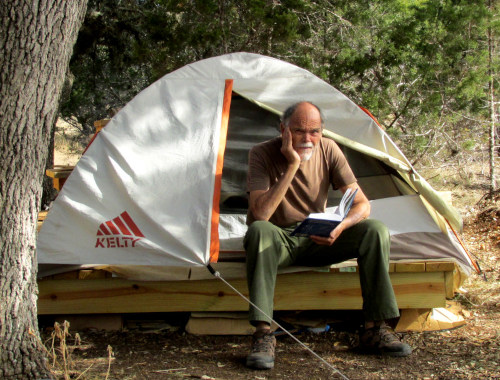

Above, that's me, naturalist Jim Conrad, who in 2020, at age 73, wrote the first edition of this tree of thought, feeling and intuition. I'm camped on a property in southwestern Texas, where I bartered two hours of physical labor each day to pay for the camping site, daily access to the property owner's electricity (for my laptop), and wifi connection. Both before and after the Texas visit, I lived in various places in Mexico and elsewhere.

{ Below, each entry is linked to a section }

This tree of thought, feeling and intuition documents my personal search for peace of mind and a little happiness. My goal was achieved only after many years of meditative Nature-study imparted the following two insights, in which all the following is rooted:

Attaining peace of mind and a little happiness mainly is a matter of managing one's own mind, which is hard work.

Mother Nature is the best teacher and therapist, because She's everything real around us, not someone else's opinions.

The following describes the path I took.

Here's how it's been for me over the last half century of practicing meditative Nature study:

You identify something in Nature, then look up its name to see what's interesting about it. You keep gathering information and having experiences with that thing for as long as you can.

If you're lucky, you'll do this for the rest of your life, with lots of plants, animals, fungi, algae, rocks, cloud types, stars, ecosystems, geological formations, natural processes... and people, because people are part of Nature, too.

You study in a special meditative way, always focusing clearly and calmly on the thing at hand, its manner of being, its importance, its beauty and any message it may have for you. At a certain point -- months or maybe years into into the meditative Nature-study process -- something mysterious and wonderful happens:

Somehow, what you've been learning and experiencing under Nature's influence imparts to you what feel like insights and intuitions. These insights and intuitions propose right-feeling

Though somehow the answers Nature seems to be revealing may feel right, and are confirmed by how life on Earth and the human condition are seen to be evolving -- even confirmed by experiments based on the principles of quantum mechanics -- these proposed answers can't be verified, or even properly articulated in words.

My experience, however, has been that just meditating on the mystifying, dazzling reality which meditative Nature-study has suggested to me, has resulted in a certain acceptance of myself as a natural component of the whole thing.

And that acceptance has translated into a low-grade but sustainable-for-a-while-longer general happiness, which has proven to be therapy enough.

In the spring of 1966, as a young man back on the farm in Bible Belt rural Kentucky, USA, I was a mess. One day I felt so disgusted with myself that, just so my parents wouldn't have to look at me, or I, them, I skulked into a swampy forest about half a mile from the farmhouse where we lived and simply sat on a fallen tree trunk. I didn't go home until sundown. The next two days, it was the same.

On the third day, however, my suffocating sense of inadequacy dissipated enough for me to notice a mushroom emerging from a log on the forest floor just a few feet in front of me. This was the exact moment in my life when my bogged-down mind and spirit began the awakening process I want to tell you about.

That day, sitting on the log in the swampy forest, I asked myself: Why was that mushroom growing on a log and not on the ground? I got down on my hands and knees and looked at the mushroom closely. Beneath its top, what were those thin partitions radiating outward from the stem? Was the mushroom poisonous? Could I eat it?

That night in my mother-bought M volume of Funk & Wagnalls Standard Reference Encyclopedia for 1959 I looked up "mushroom." The mushroom's top was called a cap, and the partitions were gills. Reproductive spores fell from the gills, to be carried away by the wind. The mushroom itself was just a reproductive structure arising from a body of white, cobwebby hyphae growing inside the prostrate tree trunk, decomposing it.

The next day I went back and for a long time just looked at that mushroom, seeing it in a way I'd never seen anything else before.

In a way, you could say that over the next few days the mushroom and other inhabitants of the little forest drew me into a state of intense enchantment that has never ended. "Enchantment," both in the sense of being under a spell, and of experiencing great pleasure.

For over half a century now, many thousands of times I've reproduced the procedure just described, though in a more practiced manner, with birds, wildflowers, rocks, etc. I'd identify something, look it up and learn all I could about it, then keep learning more and more about it as the years went on, and here's what always happened:

It always -- always -- made me feel better.

And back when my mushroom story took place, I desperately needed to feel better. My first year at college had been rough. Because of poor grades, I'd qualified for probation the first semester. Moreover, I was a pimply, 340 pound (154kg) teenager burbling with hormones, too ashamed of my flabby body and too bashful ever to say hi to a girl. I'd come to college without knowing how to take good notes in class, and I didn't socialize, for I didn't know how to do that, either.

However, just remembering my mushroom days helped me cope with my inadequacies as a university student. In fact, I was thinking about the swamp back home when one day I walked into the college bookstore, just to have something to do.

On one the store's shelves I found books about meditation, with covers promising greater tranquility and general happiness. I bought a book, learned some simple meditation techniques -- sit quietly, close your eyes, focus on your breathing -- which actually did make me feel better. My Nature studies back in the swamp had helped me more, but now I'd found a second path, one available when I couldn't enter the forest.

Eventually it occurred to me that Nature study itself is a genuine meditation. Meditation is defined as contemplating or reflecting, as opposed to simply noting something, or learning about it without digging into "what it all means."

Any form of meditation, including what eventually I began thinking of as Nature-study meditation, requires real effort and intent. Therefore, to help keep you from giving up on the process before you notice its benefits, it's helpful to keep in mind that any meditation is likely to provide positive results. According to the Healthline.com website, here are clinically confirmed benefits granted by various forms of meditation:

Meditation...

In terms of meditative Nature-study, the above-mentioned "lengthens attention span" is almost an understatement. Many times I've been so absorbed in watching ants capture a grasshopper, or maybe photographing the interior structure of a flower, that suddenly -- because I'd been holding my breath while focusing so intently on what was at hand -- I found myself gasping for air. Sometimes for days or weeks at a time I've worked on a particular mystery, such as determining which frog species was leaving a certain kind of gelatinous egg mass in a barnyard watering trough.

The above list mentions "generating kindness." I know exactly what is meant. The more you understand and experience the things of Nature -- and we'll see that humans also are things of Nature -- the more empathy you feel for them. Even a spider, if you get to know one, with its perfect web, its daily and nightly routines, its obvious nervousness if something big and possibly dangerous gets caught in the web, the unexpectedly pretty and artful colors and designs on the spider's cephalothorax, those eight eyes looking back at you when you get close... even spiders can be welcome neighbors you're glad to show kindness to by leaving them alone.

Also, an important feature of any meditation is that it can be performed anywhere. That's especially true with Nature-study meditation, exactly because Nature, we'll see, is everywhere, because it's everything .

Meditative Nature-study nearly always makes a person more mellow, empathetic, and certainly more knowledgeable about the surrounding living world. If the process continues long enough, eventually the new you may feel at odds with the life you've been leading. You might decide you need to change your way of living, so that you're more in harmony with the natural world you're starting to discover.

However, it's hard to change in substantial ways.

It's especially hard when living in a society very much at odds with your new insights and feelings. If you change much, often people think of you as disrespectful of traditional values, maybe of being deviant, of wanting to draw attention to yourself, or they just think you're crazy. In societies obsessed with earning money and keeping busy all the time, if you take the time to think, deeply experience and meditatem you may be considered by many to be lazy and parasitic on everyone else. I know this from experience.

Let me tell you how I became a hermit.

After acquiring an MSc degree in Botany at the University of Kentucky, first I became a park naturalist in Kentucky, then I did botanical work at the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis. For the Botanical Garden I collected plants for taxonomic study in several tropical American countries. Then for many years I worked as a freelance writer, mostly publishing on Nature themes, visiting about forty countries in the process. I earned just enough money to keep doing what I was doing.

During that time I saw with my own eyes the sad state of the planetary biosphere. Studying the history and local manias of the places I visited, everywhere I learned confusing and troubling facts about human nature, behavior, and the inevitable consequences thereof. The world was in trouble -- the people, and life on Earth in general.

Early on I began wanting to disengage from the way things were going, and try to live in a manner I thought of as appropriate. However, making such a big change was too hard for me. Years, decades, passed without my making the appropriate big changes.

In the fall of 1996, my relationship with a lady in Belgium failed at the same time I learned that my mother was dying of cancer. Upon my mother's death, back in the US, I moved onto a large, historic plantation south of Natchez, Mississippi, which I'd visited years earlier while working on a magazine story. There, in early 1997, at age 49, I became a Nature-studying hermit.

I moved into the tiniest, most hangdog-looking, used trailer you can imagine, parked in seclusion in a piney forest. The years that followed began the happiest, most creative and productive period of my life.

I lived the Mississippi hermit life for about 7½ years. My trailer occupied a long-abandoned, semi-open spot where years earlier a house had collapsed leaving nothing but a rusting tin roof. However, electrical lines to the former building remained, and I got connected. In 2001 I ran a wire through the woods to a hunters' camp, tapped onto their phone line, and went online with a computer I'd put together from three or four broken-down ones.

During those early days of the general public having access to the Internet, I began creating websites, doing the HTML code one keystroke at a time. My first website offered free web pages to small ecotourism undertakings all over the world. This was before Facebook and other such services, so I got plenty of takers in many countries. Though sometimes months passed without my speaking face-to-face with a single person, on the Internet I was in daily contact with people in fascinating places all over the world, doing interesting things.

At that time my thoughts and feelings began blossoming in ways that earlier I hadn't even suspected were possible. For example, I began conceiving of information flow from one node of human mentality to another -- with me as one node among a world of others -- as like energy flow in an ecosystem, from one species or individual organism to another. Facts were sub-units of ideas and concepts, just like plants and animals were sub-units of Earth's forests and oceans, and I was one of those sub-unit animals in the Mississippi forest.

But, before continuing, here's this:

During my Mississippi hermit days I began issuing a weekly online "Naturalist Newsletter" mostly concerning the plants and animals around me, but also often carrying essays about my Nature-inspired thinking and feeling. Numerous of those essays are included in this tree of thought, feeling and intuition because they provide different perspectives about the particular subjects we'll be dealing with.

Different perspectives are needed because many ideas considered here are like hard-to-see stars: You look directly at one and it disappears, but you look a little to its side and your peripheral vision registers it, even though you can't focus on it directly.

Nature study teaches that there's a lot like that when you're a sentient being in this Universe.

Here's a Newsletter suggesting one aspect of what life was like during those days. It was issued from my camp via a dial-up modem, and accompanied by a sonorous Pshhhkkkkkk-rrrrkakingkakingkaking-tshchchchchchchchcch-*ding*ding*ding" gushing through wires running from my little trailer to the hunter's camp, and beyond. It's dated January 5th, 2003:

This has been a chilly week with several frosty mornings. With the plastic tarpaulin over my trailer, the windows plugged with Styrofoam boards, and blankets draped over the ill-fitting door, inside the trailer I remain comfortable, even cozy. With windows and door-cracks sealed, it's dark inside and feels like a small cave.

At night I remain toasty inside a good sleeping bag and during days the heat of my computer and my own body keep the trailer's small space warm enough. I wear several layers of clothing and often work at the keyboard in fingerless gloves. My main problem is that sometimes the oxygen runs low and I must let in fresh air. Then heat escapes like a frightened wren.

This entire last summer I never once turned on a fan (most days I wore clothing only for jogging and working in the garden), and I'm hoping to make it through this winter without once using the small electric space-heater kept for emergencies. Some years I've managed, others I've needed the heater, though never for more than a few minutes each day. This week last year we had a 14° (-10°C) morning and I was glad to have the heater then.

I used to keep quiet about my living style, especially about my insistence on not wasting energy. I know that most people who see how I live regard me as either despicably miserly or else mentally unstable. When our hunters meet me on the road some of them address me as if I were a child, or the village idiot. Though they can hear that I speak normally, they haven't the resources to interpret my appearance in any other way.

When I am in a regular US home and either the air conditioner or heat pump drones on and on, it weighs on me. I cannot but keep thinking of the vast environmental destruction caused in the name of my physical comfort. Land lost to coal mining, the production of greenhouse gases, radioactive wastes... all to produce energy to have me feel cooler or warmer without needing to add or remove clothing.

When at night I turn off my energy-efficient computer and my little 40-watt, high-intensity reading lamp, not an electron flows in my trailer. While I sleep, no ecological violence is committed on behalf of my comfort, and maybe that's one reason I sleep so soundly and awaken so glad.

During my school years of formally studying biology, organisms around me had become what books and professors told me they were. I identified organisms by noting clusters of field-marks. Populations had distributions which were mappable. Species occupied specific ecological niches. Sometimes certain animal behaviors could be learned but most behavior was instinctual. However, in the Mississippi woods, my life merged with many lives in ways books and professors didn't tell me about.

To hint at what I mean, here's another Newsletter entry, this one dated June 13, 2004. By this time I'd moved to another spot in the forest, this location having a barn with an old cow stall I used as an office:

Just after dawn on Tuesday morning I realized that something was missing. For several days the Carolina Wrens had been carrying bugs to their second-hatched brood of the year. I'd grown accustomed to their perpetual flying in and out of the tool room across from my computer room in the barn. Tuesday morning all was quiet, so I knew that the nestlings had left their nest. In times past I've seen that once the nest is abandoned the whole family avoids me for a week or two.

However, in mid morning I heard a beseeching peep from inside the barn's garbage can. Inside was one of the nestlings barely keeping his head above the water pooled there after recent rains (leaky roof). I could imagine the whole sequence of events: One by one the nestlings had been coaxed to fly from their nest on the high shelf in the tool room and this one had made it out of the room as far as the trashcan's rim, but he'd bungled his first landing, tipping into the can. Once his feathers were wet he couldn't fly out. The family had gone on without him.

I dried him off and set him on the barn's concrete floor outside my door where for a long time he just sat looking around. After an hour or so he began peeping and hopping about. Finally around noon one of the adults returned flying here and there and the classic Haiku by Kobayashi Issa came to mind:

A plaintive peep, a sturdy reply, a flutter of wings upward, and within moments an open beak was plugged with a green grasshopper.

After a few more feedings both birds disappeared the way wrens are supposed to on the first day of fledging.

As a hermit in Mississippi, for the first time in my life I felt that I had the time to think things out. Now I confronted emotional issues, made decisions about how to deal with them, did the needed thinking, and changed my behavior if needed, and if I could. Now I gave free reign to my curiosity, letting it guide me wherever it led. A big limitation in that life was that the days were far too short to deal with everything I wanted to. However, by dusk, always I was so pleasantly tired that sleep was welcome.

And here's something interesting: All during those years, and all the years since, I don't believe I ever developed a single basic idea that as a kid or adolescent I'd not fleetingly glimpsed, but let the insight fade way.

Probably all us humans are the same way. All of us, I bet, when quite young, have moments of deep insight, but normally we ignore them, forget them, and lose them.

During my hermit days consciously I tried to recall and salvage those youthful insights. Once I'd retrieved one, I'd focus on it, examine what it was trying to say, and think about the implications.

Here's a Newsletter entry in which I was reviving and nurturing one such insight that had been riding around inside me since the 1960s. Eventually this insight would become an important cornerstone in my Nature-study-therapy, old-man philosophy. It's dated September 9, 2001:

I’ve been watching a Garden Spider lately. This has got me thinking about an experiment I read about long ago. Different chemicals were given a spider to see how each chemical would affect the spider's web. Most striking was how the spider given marijuana's active ingredient produced a sloppy web with many incorrect connections and holes. On the other hand, when the spider was given the active ingredient in LSD, the web produced was perfect, as if the chemical had increased the spider's power of concentration.

It makes one wonder how much our own realities are affected by whatever chemicals or hormones happen to be flowing in our veins at the moment. Could just the right knock to my head or a change in my diet convert me from a happy hermit to a nervous land-developer overnight.

I wonder about these things a lot, especially because I am hypoglycemic. If I happen to stoop for a while and then stand up quickly, things go black and I'm lucky if I can keep standing. Then as blood sugar slowly returns to my brain I become able to take a few steps, though I seem to see things through a tunnel. Finally I return to full consciousness. I think that this happens to everyone, but with me it is a daily, sometimes hourly event.

Thing is, during those few seconds when I'm able to walk but see things as if through a tunnel, I think I'm fully recovered, and actually feel happy that once again I can concentrate so clearly on the ground before me and walk with such self assurance. It's only moments later when I'm really normal that I remember back to my tunnel-walking moments just a second or two earlier and realize that as I'd tunnel-walked my thoughts and insights had been profoundly limited.

In other words, several times a day I remind myself that the very dumb can never know just how dumb they are. I am also struck by the fact that during the first few moments of "being myself," I can still recall exactly how it was to be "tunnel walking," and I am appalled at how self-centered and narrow the tunnel-walking headset was.

Moreover, how can I know that when I'm "normal" there isn't an even more lucid state beyond that, one in which I could "be more myself" if I only had the brain to go there.

In fact, because of very brief moments of insight accomplished during moments of meditation, I am sure that those higher levels of enlightenment do exist.

Recollections of insights understood during those brief moments of enlightenment have a little to do with why I am now a hermit in the woods. However, now in my "normal" state, I am really too dumb to explain to you clearly how my reasoning works.

A few months after writing the above, one night some packrats triggered further thoughts on the matter. The following Newsletter shows how during those days my Nature-inspired thoughts were building upon one another, just like biological evolution proceeds by causing new, more sophisticated species to arise from pre-existing ones. The following is dated February 24, 2002:

Monday morning I awoke groggy and annoyed because the Eastern Woodrats introduced in the December 9 Newsletter had thumped and bumped all night beneath the trailer. This was unusual because the rats have done that all winter and usually I find their presence good company. Often I have to laugh, imagining what shenanigans must be going on below for such unlikely noises to be produced.

"Pickle juice," I concluded.

Kathy the plantation manager periodically cleans out her refrigerator and sometimes I am the beneficiary when she sends my way her sour milk (good in cornbread batter), fungusy cheese, and delicacies such as pickleless pickle juice (also good in cornbread batter). Well, the day before the woodrats, Kathy had set next to the garden gate a jar with pickle juice in it and I had used it.

Like so much in the American diet, this pickle juice contained outrageous concentrations of salt. Just a little salt causes me to retain water so that within an hour or two I get blurry-eyed, my ears ring, I can't think or sleep well, and later feel grumpy. One day all's right with the world, then some salt slips into my diet, and the next day the world is wretched and insidious.

This is worth thinking about.

For, is the real "me" the one with or without pickle juice? What are the implications when we discover that we think and feel basically what the chemistry in our bodies at that particular moment determines that we think and feel? And if what we think and feel isn't at the root of what we "are," then just what is the definition of what we "are"?

Actually, I can shrug off that question, but only because a larger one nudges it aside. That is, is "reality" like Chopin's gauzy, dreamy etudes, the way I experienced it on Sunday, or more like Schönberg's angry, disjointed, atonal piano pieces, the way I experienced it on Monday after taking into my body the pickle juice?

Thoughts like these have led me to distrust all my assumptions about life no matter how obviously "right" or "wrong" they appear at the moment. I have long noted how huge blocks of my behavior appear to depend exactly on how much testosterone happens to flow in my blood. An acquaintance's tendency to weepiness corresponds precisely to whether he's taken his blood pressure medicine and another's whole personality depends on her remembering to take her lithium pills.

In the end, however, you have to accept certain assumptions just to get through the day, even if you don't quite trust them. I have chosen two insights in particular to serve as bedrock on which all my other assumptions about life and living rest.

One insight arises from meditating on the grandness, the complexity, the beauty and majesty of Nature -- the Universe at large -- and thus I recognize that the Universe has a Creator worth contemplating. (This has absolutely nothing to do with religiosity, by the way, for religions are man-made institutions.)

The other insight (having nothing to do with pickle juice) is that love in whatever context is worth seeking and sharing.

This latter insight is the one that keeps me hanging around in this quaint biological entity, my body, with or without pickle juice.

Above, I use the word "Creator" and refer to the Universe as a creation. Also, I make a distinction between religions and spirituality. It's true that my meditative Nature-studies brought about in me a new focus on my spiritual state. Moreover, part of that new spiritual awareness was the insight that religiosity and Nature-inspired spirituality are two very different matters.

For me, religions are systems of belief usually based on sacred texts, and which require adherents to believe certain points of dogma. Religions usually have a priesthood which conducts rituals and ceremonies in a communal context.

In contrast, Nature-inspired spirituality recognizes no sacred text other than Nature Herself. Natural spirituality requires no particular dogmatic belief, no rituals or ceremonies, there are no priests, and -- here's the most critical difference -- instead of being a static belief system,

Admittedly, many great thinkers of modern times don't make such a distinction between religions and spirituality, at least not publicly. Albert Einstein, in his 1954 book Ideas and Opinions, maintained that the strongest and noblest motive for scientific work was "...the cosmic religious feeling."

Maybe Einstein avoided using the word "spiritual" because, in some circles, during his time and ours, the term has been associated with such practices as astrology, healing with crystals, witchery, rebirthing, past life regressions, drumming, pyramid power, etc. The Experts' Blog of Psychology Today's website at this writing includes an essay entitled "Why Do Spiritual People Seem So Flaky?"

However, by qualifying his feeling as "cosmic," Einstein made clear that his context was the cosmos -- "cosmos" being the whole Universe -- not any structured, Earth-base, human-practiced religion. His "cosmic religious feeling" was inspired not by a prophet or sacred text, but by all-inclusive "Nature."

The following Newsletter entry dated February 8, 2004 was issued from the hermit camp two years after the above pickle-juice essay was written, when I was still a bit touchy about certain features of the US Bible Belt culture in which physically I was deeply embedded:

One morning this week while listening to Public Radio I wandered over to the little pond beside the barn to check on the frog eggs. While admiring them and cogitating, the radio reported that officials in Georgia sought to remove the word "evolution" from that state's school curricula.

That juxtaposition of my frog-egg reverie with the news from Georgia cast me into a certain combative mood. How dare they seek to rob me of one of the most important words I use when cataloging the wonders I ascribe to the Creator. This news from Georgia got me to thinking this: Maybe now is as good a time as any to clearly and concisely explain why I am so anti-religious -- why I am a hardcore, dyed-in-the-wool PAGAN.

It is precisely because I regard all religions as artificial, unnecessary barriers between people and the higher states of spirituality to which they naturally aspire.

We look into the heavens, experience love, or contemplate frog eggs, and we become aware that something, somewhere, has created these marvelous things and circumstances, and that this Creator and the creation itself are worthy of reverence. Human spirituality begins like this and should continue through our lives in the same vein, perpetually growing and maturing. The highest calling of every community should be to nurture its citizens' quests for spirituality, to inspire them toward ever-more exquisite sensitivities and insights, and to encourage them to love, respect and protect that tiny part of the creation into which we all have been born.

Instead, religions divert the energies of our innate spirituality-seeking urges into the practicing of mindless ceremonies and rituals having little or nothing to do with the majesty and meanings of the Universe. Religions insist that we must disbelieve the evidences of our own minds and hearts, and submit to primitive scriptures interpreted and transmogrified by untold generations of clerics who, history reports, all too often have hustled to promote their own bureaucratic and political agendas, and continue to do so today.

In my opinion, anyone wishing to "get right with God" should begin with cleansing from his or her own life all traces of religion. And the first step in doing that is to get straight in one's mind what is religion (dogma in scriptures), what is spirituality (one's personal relationship with the Creator and the creation), and what is love (intense empathy and well-meaning). You do not need to believe in someone else's curious dogma in order to be spiritual, or to love your neighbor and do good works.

Finally, why is a diatribe like this appropriate for a naturalist's newsletter? It is appropriate because this Newsletter springs from my passion for all that is natural -- the Creator's Earthly creation. Natural things on our planet are now being destroyed at a rate greater than at any other time in the history of the human species. That destruction is being committed at an ever-increasing rate by human societies such as our own that are more and more rationalizing and excusing their excesses in terms of religious doctrine.

As this is being edited in 2024, having been mellowed by twenty more years of meditative Nature-study, I no longer bear such strong feelings of resentment against Bible Belt teachings and culture. Still, today the points raised in the essay are more important to consider than ever, so the essay is staying here exactly as it is.

The entire meditative Nature-study therapy process is premised on the notion that that Nature can teach. The following Newsletter entry demonstrates how Nature taught me something. It's dated July 18, 2004:

The other day one of my favorite local folks dropped by to share some of his delicious blueberries, and to chat for a bit. This time his remark that got me going was that I knew how progressive he was on matters BUT, when it came to gay marriages, he just couldn't take it, and surely Nature doesn't put up with things such as that.

I couldn't ignore my friend's assertion that Nature doesn't put up with such things as homosexuality.

For, nothing is more experimental and broad-minded than Mother Nature. When you look at the Creation you clearly see that the Creator's plan is to create diversity at all levels of reality, and to evolve that diversity to ever higher levels of sophistication -- whether it's forming galaxies from hydrogen gas, or evolving life on Earth. Just about any strategy furthering those blossomings is acceptable.

Among plants, sometimes flowers possess both male and female sex organs, sometimes they are unisexual and on different plants, sometimes unisexual and bisexual flowers are on the same plants, sometimes flowers are designed so they can't self-pollinate, other times they have to pollinate themselves, and some plants skip the sex scene altogether by reproducing vegetatively.

Among animals we find everything from the male seahorse who carries the eggs, hatches them and takes care of the young, to the "polyandrous" Spotted Sandpiper whose females lay in as many as four nests in a season, each equipped with a different male incubating the eggs. Of course the common earthworm is both male and female, and some snails sometimes mate with themselves, producing offspring.

The higher up the evolutionary scale you go, the kinkier it all gets. Among communities of mice and other mammals, when population density reaches a certain high level where diseases and famine threaten, not only does homosexual behavior appear but also parents begin killing their own offspring. It's always the case that the Creator chooses the welfare of the community over that of the individual.

If you can use a search engine artfully, you can find technical academic papers detailing homosexual behaviors in a wide variety of primates, from langurs to orangutans to pit-tailed macaques.

Among human populations, homosexuality occurs at a certain rate in all populations. Thus homosexuality is natural and inevitable. Data suggests that homosexuality may be at least partly genetically determined.

In short, it's simply wrong to say that homosexual behavior is never natural.

Why would the Creator create this state of affairs among humans? I don't know, but my own experience with human gays is that, on the average, they are more sensitive, insightful and caring than the rest of us, so maybe that's enough of an answer right there.

With regard to the morality of it all, I would say that at this time when so many young people desperately need love and care, and so many gay couples want to provide stable family structures for providing that love and care, the Bush doctrine of institutionalizing laws to prevent gay couples from enjoying the kind of legal and social support non-gay families already have, is immoral.

Moreover, since the Creator has made it so that among higher mammals homosexual behavior increases in populations under stress, and humanity right now, because of overpopulation and inequitable distribution of resources, is under enormous stress, the phenomenon of gays suddenly stepping forth to demand their right to establish stable family units while not themselves contributing to even greater overpopulation, can be seen to be not only natural but also, literally, a godsend.

George Washington Carver (1864?-1943) expressed it very nicely:

Albert Einstein (1879-1955) said:

Thomas Berry (1914-2009) said:

Juvenal about 1900 years ago wrote:

Rachel Carson (1907-1964) wrote:

Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) believed:

Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959) wrote:

The Christian-Hebrew Bible, Job 12:7-10:

Bernard of Clairvaux (St. Bernard) (c 1090–1153) wrote:

Isaac Newton (1643–1727) wrote:

And William Wordsworth (1770-1850) wrote it very succinctly:

This is from the Newsletter of October 31, 2010 issued from Hacienda Chichen Resort adjoining Chichén Itzá Ruins in Yucatán, Mexico:

Eric in New York sent an essay by Wendell Berry, a much respected professor, writer and farmer in Kentucky. In the essay Berry describes his agrarian economic perspective this way.

"I would put nature first, the economies of land use second, the manufacturing economy third, and the consumer economy fourth.

You can see the wisdom in this. Since all things humans need derive from Nature, Nature's welfare should be humanity's first concern. More than anything, manufacturing and consumption should reflect what Nature sustainably can provide. Moreover, some resources, such as clean water and rich agricultural soil, should be protected as priceless.

Today's dominant economies practice exactly the opposite of this wisdom. Today Nature is destroyed by economies geared to provide what people want, not what they necessarily need, and everything has a price. And often that price is way out of line with the resource's actual value.

Wendell Berry states his wisdom clearly and artfully, like many others, yet this wisdom goes unused. For every person enlightened and changed by lucid thought, ten thousand others just want more, more, more.

Can anything be done to cause the generous, life-saving messages of Wendell Berry and others to take root in today's world?

Most of my life I haven't thought so. However, living among the Maya, now I'm starting to wonder. The reason is that every day I see how a "basic assumption about life" profoundly affects everyday behavior.

For example, Maya society is rooted in a basic assumption about proper human interactions that is completely different from what motivates us Northerners. To the Maya, nothing is more important than solidarity with family, friends and community. We Northerners say we believe in those things, but you know how we let our families split up, or friends drift away, and our communities decay as individually we work very hard for money and status, or at least for conformity with those around us.

So, is it possible that one or more changes in basic assumptions about how humans should interact could cause the philosophies of Wendell Berry and the Maya to become more attractive to humanity in general? Could such a paradigm shift save Life on Earth?

Maybe. Such changes in basic assumptions occur all the time. For example, the belief system of the old farmers I knew in rural/small-town Kentucky back in the 1950s was more like today's Mayas' than that of today's rural Kentuckians. During my 63 years of living I've witnessed a profound cultural paradigm shift take place in rural/small-town Kentucky. I think that the messages of TV mainly caused it. Maybe heightened awareness arising from the Internet will engender the next big change.

If such a profound change happened once, maybe it can happen again. And maybe this time the change will trend toward the wisdom of Wendell Berry and the Maya, not against.

By the way, the above is the first of several Newsletter entries written in a hut at Hacienda Chichen Resort adjoining Chichén Itzá Ruins in Yucatán, México. I lived there for about for about 3½ years, which were good years for me and I'm grateful to the resort owners for providing the hut for me. I lived more or less as a hermit away from the general rush of things, but still interacted with the local Maya people and international tourists passing through interested in Nature. I offered free walk-abouts through the resort's gardens. Here's a picture of the hut:

At the heart of the Nature-as-teacher concept, a certain issue needs to be settled. That is, just what is Nature?

Above, St. Bernard refers to "trees and stones," but when Einstein and Isaac Newton direct us to Nature's teachings one suspects that they're referring to something beyond that.

In the Google search engine if you type the keywords "define Nature" you're told that Nature is:

Probably this definition is accepted by most people, but in this tree of thought, feeling and intuition, it is not. Nature's definition has been discussed and debated for a long time.

In their 2020 essay "What does 'Nature' mean?", found at the Nature.Com website, Frédéric Ducarme and Denis Couvet write that "It appears that this word aggregated successively different and sometimes conflicting meanings throughout its history." Ducarme and Couvet divide Nature's many definitions into four main groupings. Curiously, the common notion that Nature is just butterflies, wildflowers, and such doesn't appear to fit any of those groupings. Nor does the truly all-conclusive concept, which back in the mid 1600s was first stated in relatively modern times, in Latin, by the Renaissance philosopher Baruch Spinoza.

Spinoza wrote that in all the Universe there is only one "Substance," which is absolutely infinite, self-caused, and eternal. In his Book IV of the Ethics he called that "Substance" Deus sive Natura, meaning "God or Nature." He said that while God/Nature has no thoughts or feelings, we "modifications" or "modes" can have them. Since we "modifications" are manifestations of "God or Nature," it seems that to Spinoza even thoughts and feelings were part of Nature.

At this writing, at the HumansAndNature.Org website of the Center for Humans & Nature in Australia, Freya Mathews' essay "Nature as The Law Within US" says that in its broadest sense the term Nature encompasses everything falling under the laws of physics. That definition clearly includes humans.

Freya Mathews further writes that the belief that we humans have moral dominion over Nature is proving catastrophically wrongheaded on a planetary scale.

My position on humans having dominion over Nature was expressed in the Newsletter of November 1, 2005 written at Hacienda San Juan Lizarraga one km east of Telchac Pueblo, Yucatan, MEXICO:

The other day, for an online magazine in Holland, I wrote an essay on how -- if we are to save Life on Earth -- we humans must awaken from our hypnotic trances, begin seeing things clearly, and change our behaviors. Dirk Damsma, a professional economist at the University of Amsterdam, wrote saying that he agreed, and asked me what I thought about protecting nature by putting a price on it.

"... as soon as nature can be priced, protecting it can become profitable," he suggested. Here was my reply:

I disagree with your idea that placing a price on nature is the best way to protect it.

The workings of market forces seldom live up to the promise of their theoretical underpinning, supply and demand. Market prices are much distorted by such things as subsidies, sales taxes, embargos and the rapacious, self-serving behavior of very rich and powerful people and organizations. There is no reason to believe that if we apply market principles to nature the things of nature will ever be designated as having prices even approaching their real values.

For, with nature the stakes are higher than with the things market principles are concerned with. A manufactured cog can be stored, reused, sold at discounts, etc., but once a species goes extinct, millions of years of evolutionary wisdom are simply lost, never to be reclaimed. When a rainforest is destroyed, a rainforest does not grow back. The destruction of a rainforest changes soil and microclimate conditions so drastically that what grow back are weeds, not rainforest.

You might say that I need to be realistic, that I need to compromise just a little and accept practices real people in the "real world" can handle.

I say that the "real world" of Western-style commerce as it has become with neoconservative globalization is so perverse, so self-serving and so void of all feeling for average people and other living things that there is nothing realistic about it. Just look at the price Americans must pay for their medicines.

Awakening from the trance we are in must be a holistic experience. Putting a price on the components of nature would be no more than a gimmick that would perpetuate the false notion that nature is composed of discrete, independent parts. Also, it would perpetuate the lie that we can spend ourselves out of trouble without needing to change our own behaviors and our ways of seeing the world around us.

On a spiritual level, it would be just as insulting to the Creative Force of the Universe for the things of nature to wear price tags as it would be to place a monetary value on a mother's love for her child, or the way you feel when you "go home," or when you gaze into the starry sky at night.

Accepting the concept of "Nature as teacher" doesn't imply that if we see a snake capture and swallow a frog, we humans should be prey on and eat animals more vulnerable than ourselves. Acceptance of the concept does imply this: If seeing the snake capture and slowly swallow the frog elicits some sense of revulsion in you, maybe your revulsion is revealing something about you and your relationship with other animals. Maybe you need to think about it and deal with it.

For example, maybe if you have have an animal friend like a canary in a cage, and begin noticing that your canary has moods and idiosyncrasies, that the bird is smarter or dumber than other canaries you've known, that maybe the canary shows some affection for you, and if as you gain this familiarity you begin feeling empathetic toward this canary... maybe you should honor your impulse to be kind to and protective of that canary.

Moreover, when you think about it, since your canary's personality probably is similar to that of other bird-brained animals, such as the Earth's 30 billion or so chickens, maybe for the same reasons you wouldn't kill and eat your canary you shouldn't kill and eat chickens, or pay others to kill them so you can eat them. In fact, since pigs, cows and other animals may display even more emotions and forms of mentality than your canary, maybe you should be a vegetarian...

In other words, Nature's teachings may be interpreted in different ways. But, how do we choose the right interpretation? The answer is, instead of blindly accepting received ideas and practices from society,

The following Newsletter of December 14, 2018 was issued from Rancho Regenesis near Ek Balam ruins 20kms north of Valladolid, Yucatán, Mexico:

The "Nature as teacher" and "Nature as Bible" concepts in some minds bring up this question: "Can it really be that -- as Darwin's Survival of the Fittest suggests -- the stronger is supposed to dominate, maybe even enslave or kill, the weak, like an alpha wolf within his pack, or when the wolf pack falls upon a herd of grazing deer?"

That line of reasoning overlooks a basic feature of Nature as manifested here on Earth: The evolution of Life on Earth has shown direction. With the definiteness of an arrow shot at a target, that direction was from among simple beings mechanically behaving as their genes dictated, toward us humans, of whom some of us some of the time can think and feel beyond the dictates of our genes.

Over many millions of years, in mid flight, Nature's evolutionary arrow passed through a landscape populated with organisms like reptiles, birds and early mammalian species who displayed behavior that sometimes was complex -- as building a nest of a certain kind -- but behavior still guided by innate impulses rooted in genetic coding. Among the most powerful such gene-based, innate impulses were and are the sexual drive, and the urges for status/identity, and territory/property.

Especially nowadays it's worthwhile to think clearly about which features of our thinking and feeling derive from genetically based innate drives -- the urges for sex, status, property, etc. -- and which are rooted in the higher mental domain reserved for humans. That's because at this moment in our history ever greater parts of humanity are misled by the "Survival of the Fittest" concept. They look at Donald Trump, for instance, see that he's a big winner in the sex, status and territory department, and decide that he's an exemplary being worth following and emulating.

But, Nature's arrow passed right through the evolutionary landscape featuring ever more aggressive competition for sex, status and territory, and continued beyond. Now the arrow is entering the domain of feelings and abstract thought liberated from genetic programming -- and there well may be other domains even beyond that.

To honor a winner in the sex, status and territory scene, while disregarding the significance of the thinking and feeling we humans are capable of, is to pervert one of Nature's most sacred teachings. To conduct our lives in harmony with what the Creator of the Universe has shown us She "wants" -- by sending Her arrow toward humans who can think and feel beyond the limits imposed by genetic programming -- is the highest goal a human can aspire to.

We're "ethical" when we conduct our lives in accordance with moral principles. "Moral principles" are guidelines to live by. However, moral principles are not fixed; they may change over time, and according to context.

Notice that the whole concept of ethical living is relevant only in a community context. If only one human lived on Earth, that human would do what he or she wanted or had to do, and the whole matter of ethical living would never come up. When we consider ethical living, by definition we're thinking about people's relationships with one another and to their communities.

In the past, ethical living basically meant doing what was generally approved by those around them. Nowadays the matter is much more complex.

For example, one person may feel "ethically obligated" to work hard for a church project to build new houses for homeless people. Another person may feel "ethically obligated" to oppose the building of new houses and urge instead the repair of old homes to be offered the needy. Repairing instead of building something new would save wood, thus conserve trees needed by the "greater community" of Life on Earth.

In other words, to live ethically, thinking people need to recognize the various communities they belong to, to consider what the "approved behavior" is for each community, and to recognize that their membership in some communities requires more devotion and sacrifice than for others. For meditating students of Nature, Nature offers Her own insights into "ethical living" on many levels, but nowhere is it expressed more clearly than in the manner by which biological evolution proceeds.

Genetic mutations and random low-level changes in the genetic code occur in individuals, but those changes are not preserved over many generations unless they encourage the long-term survival of the species. If a novel combination of genes makes the individual less adapted to its environment, that individual is less likely to contribute genes to the species' gene pool. But if the new combination proves advantageous, the individual is more likely to pass rgw along, and the species, not the individual, evolves in a more sustainable manner.

The following Newsletter entry dated July 19, 2009 was issued from the Siskiyou Mountains west of Grants Pass, Oregon, as my thoughts about Nature-informed ethical living finally were taking form:

You don't need to be religious to benefit from having a firm foundation for ethical living. The most eloquent, authoritative and promising of all institutions capable of informing us on ethical living is Nature.

Nature's authority for teaching us ethical living lies in this fact: As a piece of music reflects the general mood, thinking and creative method of the composer, Nature reveals the basic impulses of the Universal Creative Force. In religious terms, Nature shows us "the Will of God."

Nature is highly structured. A system of ethics can be interpreted from that structure.

For example, Nature is structured so that resources are recycled; things are not wasted. These facts amount to an ethical teaching. Nature says:

Nature's elaborate structure further reveals the Universal Creative Force's passion for diversity. Thus a second of Nature's teachings is that humans must

Nature on Earth grows ever more complex as time passes. Species continually evolve toward higher, more sophisticated, more sensitive and more informed states. From that I learn a third teaching: that also

These are three of Nature's most obvious teachings. If we were to think hard we could come up with many more teachings and develop a body of "sacred literature" as impressive and much more appropriate than any gilded Bible, Koran or Torah.

However, in humanity's current early stage of evolution during which most of our behavior still is rooted in genetic programming -- matters of sex, territory and status -- embracing just the three teachings listed above make a good start.

Just those "Three Commandments" provide a sound basis for anyone who wishes to live ethically on a small, fragile Earth.

As a farm kid growing up in Kentucky I saw with my own eyes the sharp differences in behavior between dog breeds. The collie liked to stick close to me during long walks in the fields, but the English setter always orbited around, poking his snout here and there, too obsessed with sniffing out birds to care much for simply walking along fields. Over the years, I've seen that these were behaviors typical of collies and English setters.

All dog breeds are members of the same species, Canis familiaris, so when particular dog breeds consistently exhibit distinctive behavioral characteristics that are not taught -- such as the shepherd's herding instinct, the setter's pointing instinct, the terriers' urge to dig into holes of foxes, moles and such -- those behaviors must result from predispositions the dogs inherited in their genes.

However, that isn't saying that all of a dog's -- or of a human's -- behavior is genetically programmed. Dogtime.com's "Dog Breed Center" recognizes characteristic, genetically based instinctive behaviors of many breeds, but in doing so makes clear that "Even within breeds, there's enormous variety in the way a dog acts and reacts to the world around them." In other words, genes predispose a dog, but training and life experiences can change a dog's daily behavior.

This point is important for us because humans are no less animals than dogs. Moreover, all of us animals have evolved according to the same more-or-less Darwinian principles of evolution (survival of the fittest) and, as with other animals, much human behavior is predisposed by our genetic heritage. However, also as with dogs, we humans can learn to alter, sublimate or suppress many or maybe all those innate behavioral predispositions that are disrupting our lives.

Here are two important features of this situation with regard to humans:

To get a handle on how powerful innate predispositions can be, consider the White-crowned Sparrow.

Even when newly hatched White-crowned Sparrows are hatched in incubators and thereafter kept where they never hear any bird songs, when they're about 100 days old they begin producing sounds approximating the song they'd sing in Nature. Their song is not nearly as rich and pleasant to hear as that produced by wild birds, but experienced birders definitely can hear the White-crowned Sparrow element in it. This is documented in the 2010 study by Stephanie Plamondon and others entitled "Roles of Syntax Information in Directing Song Development in White-crowned Sparrows (Zonotrichia leucophrys)."

For a long time, the science known as behavioral genetics has used genetic methods to study the nature and origins of human behavior. Many experiments in this field examine the behavior of identical twins who share the same genes but may or may not have lived similar lives. To date, as reported in the article by Matt McGue and Irving Gottesman entitled "Beahvior Genetics," appearing in The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology of 2015, behavioral genetics has arrived at three major conclusions:

The following essay, about a certain genetic heritage affecting my own quality of life, and accompanied by a picture of me at my inordinately hot forest camp, is from a Newsletter dated April 20, 2020, from Tepakán, Yucatán, MEXICO:

I told a friend, a nurse, that the unusually intense and unrelenting heat seems to have caused my ears to get infected early this year -- sweaty ear holes, I guessed. Usually they wait for the rainy season. My friend said she wasn't surprised because of my round head, highlighted above. In my 71 years no one has mentioned to me that my head is unusually round, especially for a tall person. My grandpa Conrad had a real Charlie Brown head. I've been in parts of northern Europe with lots of tall, round-headed people.

My friend explained that in round heads the Eustachian tubes -- narrow passageways between the middle ear and the pharynx, providing equalization of pressure on each side of the eardrum -- don't have enough room between jawbones and other bones, so they get clogged and infected. The tubes drain better in longer heads. I love it when things like earaches in the night can be explained so simply and obviously.

When my round head got to thinking on the matter, I remembered that, from Nature's perspective, our human species is a work in progress, with many design flaws not yet corrected. Hip and knee joints give out early, vestigial appendixes get infected and burst, teeth impact and rot in too-small mouths, backbones crunch when we move big rocks -- eyes, hair, hearing, tasting, smelling all give way in old age...

The situation can be explained by the fact that Nature concerns Herself with evolving SPECIES to higher levels, but cares little about the comfort and dignity of individual beings. We biological organisms are supposed to produce enough babies to ensure that in the long run more strong, smart and lucky people survive to pass along genes to offspring than weak, dumb, unlucky ones, and so evolution progresses.

However, we humans aren't totally enslaved to the principles of classical Darwinian evolution. Whenever any thinking being, by thinking things out and exercising self discipline, overrides his or her gene-encoded urges and predispositions -- as by walking away from a sweet, high-calorie slice of raisin pie our genes predispose us to eat -- the process of Earthly evolution "changes gears." Evolution continues in the same direction as ever, but now -- assuming that this more sustainable behavior involving self discipline is passed on to others -- it's mentality evolving, not organic species.

Individual organisms are to their evolving species as individual ideas are to evolving mentality.

When my round head thinks about it, at this moment in human evolution the potentials before us are staggering and profoundly interesting and exciting. However, precisely because human mentality is just beginning to blossom, the whole process is fragile, and vulnerable to things going wrong -- as with the first flower of spring, when late frosts still are possible.

For example, in the realm of emerging human mentality, what can be sadder than when large numbers of people start thinking it's OK to discredit scientific facts for political or economic reasons, or just to raise hell?

At the hermit camp in Mississippi, in 2008 one evening I was listening to National Public Radio's "Fresh Air" featuring an interview with Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor, who was coming out with her book My Stroke of Insight. That interview, about a right-brain, left-brain experience, supercharged a long train of thought I'd been having, about how I was to deal with my own genetic heritage.

Here's an entry from the Newsletter of July 7th, 2008 resulting from my hearing that interview:

The other day on Public Radio a brain specialist described her own experience with a stroke that left the entire left hemisphere of her brain nonfunctional. Though the stroke was a tragedy, it afforded the specialist an opportunity to study the right brain/ left brain situation.

The human brain's left side is logical, practical, and fact-oriented while the right hemisphere deals with feelings, beliefs, symbols and "the big picture."

The brain specialist explained how our two brain hemispheres cooperate to produce "us." After listening to her I visualized each human personality as like a 3-D image suspended in space where light-like beams from two different brain-projectors pass through one another. Turn off one projector, or remove one side of the brain, and the resulting projected image, or personality, changes dramatically.

Maybe the most interesting feature of the brain specialist's story was how she found being without a left brain an ecstatic experience. During her early days of not having a functioning left hemisphere she lived in a world in which she couldn't speak, but she experienced the effects of colors, textures and shapes with profound intensity, very much like someone on LSD. Sometimes during her rehabilitation, as her left brain gradually came back online -- as she learned again the complex facts of life and began realizing how she fit into a large, often frustrating and threatening world -- she often asked herself if she really wanted that left hemisphere back in her life.

Stroke victims who lose the right side of their brain instead of the left undergo completely different experiences. Such folks often find themselves overwhelmed as their left-brain hemispheres obsess on the details and ordering of life's events while being unable to judge which details are more important than others, and what they all mean.

In the workings of the two-hemisphered human brain, then, we see that the Creator isn't content having us humans all the time sitting around admiring clouds and feeling good. Nor does She want us to behave like super-rational automatons. She wants emotions to color our rationality, and She wants us to concern ourselves with both the minutia of life as well as the big picture. To me, the two-hemisphered brain is no less than a spiritual imperative to follow The Middle Path.

Thinking like this, The Middle Path reveals itself to be much more than a compromise between opposites, or the meeting place of extremes. The Middle Path is a miraculous state as charged with its own possibilities as a human personality is when it ignites into being, as a right brain hemisphere and a left brain hemisphere focus their energies onto the same spot, and self-awareness erupts.

After listening to the interview mentioned above I looked for more information on the Internet and found that hardly anything on the subject could be said without mentioning the studies of Dr. Michael Gazzaniga of the University of California at Santa Barbara. At this writing often he is recognized as the foremost expert on right-brain left-brain phenomena -- sometimes known as split-brain research. Wikipedia's Michael Gazzaniga Page tells us about Gazzaniga's "Patient W.J."

Patient W.J. was a WW II paratrooper who was hit in the head with a rifle butt, after which he began having seizures. Gazzaniga treated the problem by splitting the corpus callosum connecting the patient's two brain hemispheres. Afterwards, Gazzaniga experimented by flashing visual stimuli such as letters and light bursts into the patient's left and right eyes. Our eyes' optic nerves cross on their way to the brain, so stimuli flashed to the right eye are processed by the brain’s left hemisphere.

The brain's left hemisphere contains the language center, so when stimuli were flashed into the right eye, the patient's language-capable left hemisphere enabled him to press a button indicating that he saw the stimulus, plus he could verbally report what he had seen. However, when the stimuli were flashed to the left eye, and thus the right hemisphere without the language center, he could press the button, but could not verbally report having seen anything. When the experiment was modified to have the patient point to the stimulus that was presented to his left eye -- and not have to verbally identify it -- he was able to do so accurately.

The same patient with his corpus callosum severed also experienced conflicts between the two separated hemispheres. If he reached out to open a car door, the other hand might try to stop the hand doing the opening.

Another of Gazzaniga's patients, "Patient P.S.," was a teenage boy who underwent the same surgery. When the word “girlfriend” was flashed to his left eye, and thus his right hemisphere, he could not verbally say the name of his girlfriend, but could spell the name “Liz” using Scrabble tiles. This suggested that even though verbal language was not possible in the right hemisphere, a certain form of communication could be resorted to by gesturing and left hand movements.

There's still debate about how to interpret the above results, though the basic facts as stated are not questioned. The debate is about what scientists and philosophers call the "mind-body quandary" -- the relationship between our minds and our physical brains.

On one side of the debate are those supporting the notion that consciousness and reasoning are practically mechanical phenomena, and that a human has almost, or absolutely, no free will. On the other side is the traditional view that we humans do have free will, with nothing obliging us to "want what we want."

Whatever the case is, the above experiments at the very minimum must cause us to suspect that we ourselves may not quite be what we've always believed. Also, maybe there are mental possibilities which we're not taking advantage of, simply because we don't know about them.

As is made clear on Wikipedia's Free Will page, the debate about whether we have free will has been going on since the ancient Greeks wrote about it, and surely before. Today the issue isn't settled, though many people think it's important to know whether they do or don't. Nature's teaching to me has been to consider the question as based on an incorrect premise, thus pointless.

The Newsletter of January 2, 2020, issued from Tepakán, Yucatán, Mexico, considered the matter:

Friend Eric in Mérida lent me his book Spinoza's Book of Life by Steven Smith. It's an overview of Spinoza's very hard to read book Ethics, first published in 1677. I'm interested in Spinoza because of his influence on monist thought, and I'm a blossoming monist. Monism isn't a religion but rather a manner of thinking about the Universe/Nature.

For centuries a big question has been whether humans have free will, or are we just acting out what we're obliged or programmed to do? The no-free-will position is formally known as determinism, and as science discovers more and more human traits determined by our genes, with more and more of our behavior found to be determined by hormone levels and other physiological states of our bodies determined by genes, the trend for a long time has been toward the determinist position.

Spinoza says that free will and determinism aren't incompatible, but rather that they're two ends of a chain that must be held together. At first, Spinoza seems a convinced determinist. He writes that the more a person insists that he's free to do as he wishes, the more that person is ignorant of what causes his behavior.

However, his main thought on the matter is that free will can be attained if we learn why we think and behave as we do, and then, considering all the facts rationally, act accordingly, based on our decisions. Not only does studying ourselves and the world we live in free us, but, also, "The more we understand individual things, the more we understand God," he wrote, expressing a very monistic view.

An important feature of this insight is that once we understand why we behave as we do, if we succeed in changing our behaviors we may regret, it helps us forgive ourselves for past errors.

Knowledge is a form of power that not only interprets the world, says Spinoza, but changes it.

Nudged on by Spinoza and others, eventually I gained the monist insight that everything in the Universe is One Thing, with us things of the Universe manifesting within that One Thing; thus each of us constitutes a tiny, ephemeral zone of the Self-exploring One Thing Herself. From that perspective, the question of whether humans have free will becomes moot. There's only one will, that of the One Thing.

We'll return to this discussion later in more detail, because on the spiritual level the monist perspective can be therapeutic, even inspirational, and profoundly rooting.

Nowadays a big question among philosophers, scientists, theologians and certain regular people is "What is consciousness?" From my monist perspective, it's more insightful to wonder about -- instead of the "what" -- the "where of consciousness."

Here's a Newsletter entry suggesting how meditating on the "where" can be a beautiful and satisfying experience. It's dated January 23, 2020, a time when I lived in a tiny stone hut in the thorn forest not far from Tepakán, Yucatán, México:

Honeybees pollinating the galaxy of Goldeneye Sunflowers around the stone hut rush from blossom to blossom, staying at each flower only a second or two before hurrying to the next, never resting, like slaves with a demonic master. Why didn't honeybees evolve so that workers could occasionally rest, letting their bodies recoup?

It's because evolution has "figured out" that in terms of survival of the honeybee species, foraging workers must work exactly as hectically as they do. If workers suffer early deaths from overwork, it's easy to replace them. As always, Nature's interest is in preserving and refining the species, and if that means short, often miserable lives for individual members, so be it.

But, the situation isn't as stark as that. From my monist perspective, in which everything in the Universe seeming to have its own identity is just a manifestation WITHIN the One Thing, defining where the individual being begins and ends can become tricky.

For instance, maybe hurrying honeybees on Goldeneye Sunflowers are more analogous to hemoglobin molecules on my body's red blood cells, than to the whole me. Hemoglobin molecules transport oxygen in circulating blood of vertebrates, just as honeybees transport nectar through air to their hive. Who says that a being's interior agents must function within a single physical body, instead of flying through air on wings? Why can't the whole honeybee colony be analogous to me?

Moreover, since I'm convinced that beings besides humans can think and feel at different levels and in different ways, among honeybees, where is the seat of mentality, of consciousness?

I'd hesitate to ask such questions in public were it not that others much smarter than I are asking the same question.

For instance, neuroscientist Giulio Tononi, whose integrated information theory is a major force in the science of consciousness, has invented a unit called phi, Φ, for measuring the consciousness of entities. The word "entities" is used because maybe not only living things but even devices like thermostats may manifest at least glimmers of consciousness, of subjective selves.

Standing among honey-smelling Goldeneye Sunflowers, I sense all around me a vast symphony of entities glimmering and gushing consciousness and subjective selves utterly entangling with one another, and I sense many forms and levels of mentality and feeling nested within one another. There's the lone honeybee nested within the hive, the hive nested within the blossoming forest, the forest within Gaia the living Earth, and Gaia nested within the Solar System, which is nested in a galaxy nested in the Universe, and the Universe itself is nested as one expression of the One Thing...

In a Universe composed of 90-99% Black Matter undetectable by humans and their instruments, but recognized by human mentality paying attention to distances separating paired galaxies circling one another -- among other indications -- what's to prevent human mentality from sensing that it's possible, if not probable, that the whole shebang, from the One Thing down to this field of Goldeneye Sunflowers alive and emotional in terms of honeybees and me with my hemoglobin molecules -- at all levels and in all dimensions -- that everything is majestically supercharged and supersaturated with singing, dancing, honey-smelling Φ?

Those close with a pet know the feeling of looking into the companion's eyes and knowing beyond all doubt that there's something there staring back with its own textured feelings and manner of thinking. What an amazing feat of self-deception humanity indulges in imagining that all living things other than humans don't really think, don't really feel, on't possess anything like the human's imagined "soul," and thus simply are of no consideration with regard to a human's world view or spiritual state.

In contrast, in honey-smelling Φ mode, the mind discovers itself blossoming in a gorgeous, raucously singing garden of different-hued consciousnesses, some glowing faintly, others explosively scintillating, all diffusing into one another and all suspended within a sweet matrix itself radiant with awareness and the sense of self discovery.

If humanity soon disappears, it'll be because not enough of us learned to unreservedly empathize with, and love, other of the Earth's living things.

By the way, since writing the above essay I've learned that instead of referring to the Universe's 90-99% black matter, it's more up-to-date to distinguish dark energy from dark matter. At this writing, it's reckoned that about 68% of the Universe is dark energy while a rough 27% is dark matter. The rest -- everything in the Universe ever observed with all of humanity's senses and instruments -- adds up to about 5% of the Universe.

At least two sets of genetically based impulses predispose us to be "who we are." One set of urges consists of those shared by the whole human race, such as the sexual drive. Urges of the other set express themselves at the organism/individual level, maybe predisposing a person to be a gardener, say, instead of a soldier. The two different sets of predispositions overlap, providing a few gardening soldiers, and their relative influences change during one's lifetime.

Here's a more personal take on genetically based predispositions, from the Newsletter of May 31, 2018, written in the forest near Ek Balam ruins in central Yucatán, Mexico:

"Know thyself" is being considered here because, for me, that advice is a prime teaching of Nature. Each human is born with his or her unique set of genetically based predispositions, except for identical twins, and even the predispositions of twins diverge as different life experiences create different people of them.

Since such creative energy has gone into making my own personal package of predispositions, it seems clear to me that one of my primary tasks as a human is to recognize what my predispositions are. And, once I have figured out that, to take my predispositions into account in everyday life. My thinking is that I wouldn't have been created with definite predispositions if the Universal Creative Impulse hadn't "wanted" them to direct the course of my life.

When my Brazilian friend Iolanda was a child, she fantasized about having her own little cart on which she'd push around pans of water, soap, washrags and towels, antiseptics, bandages and drugs, and when she'd find people needing care she'd provide it. She grew up to become a nun caring for the very poor.

Even I seem the product of unambiguous genetic programming. When I was maybe twelve or thirteen I found myself on Saturday afternoons sitting at the kitchen table with information about plants and animals gathered from various sources, and writing about them in my own words. I knew no one else who did such a thing, but I felt compelled to do exactly that, and it felt good, and still does.

It's easy to see why such varied predispositions would be adaptive for the human species. In any random collection of humans, when the community reaches a certain size, automatically there are citizens predisposed to serve as teachers, farmers, handworkers, warriors, artists, exemplary parents and spouses, hunters, merchants, community leaders, etc. Our genetically programmed predispositions set us up to be useful in our respective communities.

A beautiful feature of the way all this is done is that when a person does what he or she feels most inclined to do, it makes them happy. I don't know anyone happier than Iolanda and I, even though neither of us has much money, and we're often considered by others to be cranks. My happiness, I judge, is fundamentally based on my own self knowledge.

Certainly Spinoza recognized the importance of self knowledge, and tells us exactly why: Only when we understand ourselves can we control our emotions, and that's the primary condition for sustained and rational happiness.

The corollary of knowing oneself leading to happiness is this: That by ignoring our personal predispositions we become unhappy.

In fact, maybe the great failure of our modern Western society is that so many of us have confused the needs of a materialistic capitalism with our own personal natural needs. We believe what we hear day and night -- that having this, consuming that, makes us happy.

It doesn't, at least not for Spinoza's sustained and rational happiness. Moreover, my reading of history is that any society in which a large part of the population isn't happy not only is a sad society, but a dangerous one, because of societal neuroses that inevitably develop among unfulfilled, unhappy people.

There's "good" genetic programming and "bad." In this twig, we're looking at "good" programming.

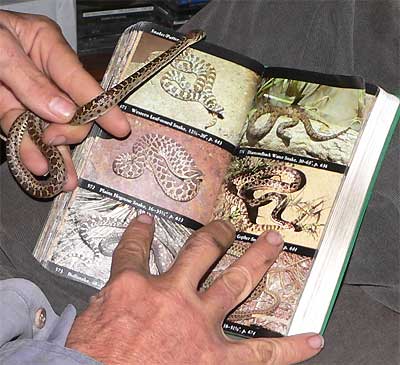

During my hermit days in Mississippi I received an important lesson on programmed behavior when one day I was walking through the forest and suddenly found myself airborne and sailing backwards. I'd almost stepped on a snake or at least something snaky. Thing is, I'd reacted so quickly that I'd jumped before realizing that it was only a tree branch curved like a snake. Wondering how that happened, I looked into the matter.