Excerpts from Jim Conrad's Naturalist Newsletter

from the December 19, 2010 Newsletter issued from Hacienda Chichen Resort beside Chichén Itzá Ruins, central Yucatán, MÉXICO; limestone bedrock, elevation ~39m (~128ft), ~N20.676°, ~W88.569°

IBE BEANS

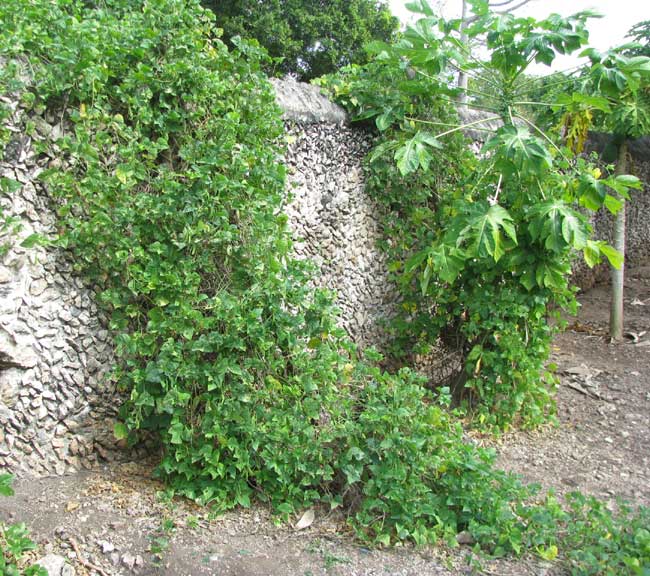

Back in the early rainy season, in June or thereabouts, Don Filomeno carved out shallow, bushel-basket-size depressions beside a stone wall next to his Papayas, filled them with soil he carried there, and planted some traditional Maya beans. Over the rainy season as my Northern garden plants succumbed to various diseases, his bean vines thrived, growing and growing, until they cascaded over the eight-ft wall and trailed down the slope. You can see what it looks like today, with some vines even entangling a Papaya, above.

By the end of the rainy season the vines still hadn't begun producing flowers. I thought that maybe the Don had used too much nitrogen, ending up with something like my Grandma Taylor did that time in Kentucky when she put too much horse manure around her tomatoes and got "All vine, no maters," as she said.

But then a few weeks ago pretty little clusters of bean flowers appeared and now the vines are heavy with bean pods, or legumes. Now that we can see what kind of beans are being produced, we can identify them, and I'm always tickled to see what these traditional Maya milpa plants, passed down generation to generation, turn out to be. You can see a clump of pods below:

Three beans nestled in a mature, cracked-open pod are shown below:

With the flat pods and beans, it's clear that they're some kind of Lima Bean or Butterbean, PHASEOLUS LUNATUS, though all Lima Beans I've ever sown have been white and considerably larger than these. When I showed the beans to Wilfredo, he called them Ibe (EE- bey), and said that there's another Maya bean almost identical, one also planted in milpas, but it's white. He could think of four Maya milpa bean types planted in this area.

Looking into the history of the Lima Bean, Phaseolus lunatus, I find that during the development of the Phaseolus lunatus cultivar two separate "domestication events" took place. The first occurred in the Andes around 4000 years ago, producing a large-seeded variety. Then about 1200 years ago, in Mesoamerica (our area), a small-seeded variety sometimes known as the Sieva Bean was developed.

Nowadays the small-seeded wild form (Sieva type) is distributed from Mexico to Argentina, generally below 1600 meters in elevation, while the large-seeded wild form (Lima type) occurs in northern Peru. The cultivar came into the hands of indigenous North Americans around 1300, and the Spanish carried them to Asia and Europe during the 1500s.

By the way, there's a story that the early Spanish conquerors of Peru exported lots of these beans, labeling their point of origin as "Lima - Peru," so that's where the name Lima Beans comes from. Another story is that the "lima" is Spanish for "lime colored," referring to the bean when green. Whichever story is true, since both "limas" derive from Spanish, if you want to pronounce the Spanish correctly, you'll call them LEE-mah Beans.

from the December 18, 2010 Newsletter issued from Hacienda Chichen Resort beside Chichén Itzá Ruins, central Yucatán, MÉXICO; limestone bedrock, elevation ~39m (~128ft), ~N20.676°, ~W88.569°

LIMA BEAN FLOWERS

The genus Phaseolus is recognized by its trifoliate leaves (with three leaflets, like clover); by the flower's style (the ovary's "neck") being hairy, or "bearded," toward the top, and; by the flower's keel (the two lower, grown-together petals) twisting into a spiral. You can see all that below:

This being a Bean Family member with "papilionaceous" flowers, the two large, white petals are the "wings," the large, greenish petal is the "standard," and the strongly curved thing arising between the two wings' bases is the "keel." We discuss papilionaceous flowers at www.backyardnature.net/fl_beans.htm.

So, at the outer end of the spiraling keel you can barely see some white fuzz and extended white stamens. That fuzz is the style's "beard" we spoke of. Why do Phaseolus flowers have spiraling keels? When you have that question, what you do is to sit down next to a flower, wait for a pollinator, and see what happens.

The pollinators I saw landed with their legs grasping the two bottom petals, the wings, so that most of the insect's weight rested on them. As the weight levered the wings down, some kind of inner linkage with the style caused the style's tip to thrust much farther from the keel, thus becoming much more likely to be dusted with pollen. You can see a flower held between my fingers with its wings depressed and showing much more of its fuzzy style than in the first picture, below:

So, the flower seems to be engineered so that until the moment of pollination its sexual parts are mostly shielded from the elements by its coiled keel, but a pollinator's weight causes those sexual parts to be thrust forward where they're more accessible for pollination.