Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

entry from field notes dated July 3, 2022, taken on the eastern lower slope of Cerro de la Cruz, at an elevation of ~2700m (~8850 ft), just south of the community of El Pinar, Amealco de Bonfil, Querétaro, MÉXICO, (~N20.17°, ~W100.17°)

IGNIMBRITE: AN OUTCROPPING BED

On the lower eastern slope of Cerro de la Cruz where the valley floor begins and the oak forest transitions to open grassy, scrubby vegetation on grossly overgrazed, firewood-collected, much eroded soil, erosion has exposed bedrock in area about the size of a basketball court, shown above. The freely downloadable 2020 geological map of the Servicio Geológico Mexicano covering this area, entitled "Amealco F14-C86," designates bedrock of this valley floor as Tp1Ig-TA, which is identified as "ignimbrita - toba andesítica," or "ignimbrite - andescitic tuff." Ignimbrite is a certain kind of hardened volcanic tuff. Tuff is a light, porous rock formed by the consolidation of volcanic ash. Andescitic tuff is about 52 to 63% by weight silica (SiO2) content.

Volcanic eruptions occurring between 3.90 and about 0.40 million years ago ejected this ignimbrite. This volcanism was a consequence of actions of plate tectonics, as explained on Wikipedia's Plate Tectonics page. Our specific instance of tectonism is the Cocos Plate grinding beneath the North American Plate, causing such friction that rock melts, expands, causes pressure within in the Earth, which is released through earthquakes and volcanic eruptions.

The subduction zone where one plate grinds below the other lies below the Pacific Ocean just off the Mexican Pacific Coast. The Western Sierra Madre mountain chain is the main continental feature resulting from that action, and we're on the edge of that. The general pinkish color of the above outcrop agrees with the pink color of our local rhyolite bedrock, of which the entire Cerro de la Cruz and much of the rest of this area is composed. Rhyolite in other regions often is whitish.

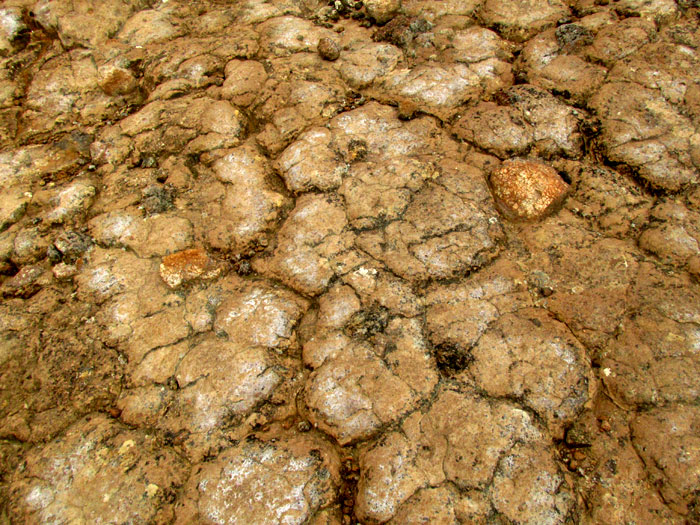

The above outcrop is particularly interesting because of the long, straight breaks, or joints, cutting across the field, and for the fracturing of the rock surface into smaller polygonal blocks. Here's a closer look at the polygonal blocks:

Y. Akiba and others in the 2020 work entitled "Geometric Attributes of Polygonal Crack Patterns in Columnar Joints" tells us that "A well-ordered polygonal crack pattern is frequently observed on the outcrop surface of columnar joints." The authors say that the pattern result from the contraction of solidified lava as it cools. Drying mud formed from fine clay particles often is seen fracturing into similar, smaller patterns. The polygonal crack patterns studied during the above research formed atop columns of polygonal shape, so I'm guessing that each of the polygonal humps in our above photo is just the top of a polygonal column extending downward.

Mingled with the pale pinkish matrix are blackish lumps which seem to be more resistant to erosion than the surrounding rock:

Parts of the field are strewn with unattached, rounded, blackish cobbles, which apparently are the dark clumps after all pink matrix has eroded from around them:

Here's a closeup showing the heterogeneous makup of one of the smaller, blackish rocks:

In the above picture, the jumbled nature of clumps and particles of different sizes, colors and erodability reflects the basic nature of ignimbrite at the time of its formation. Then, fresh from the volcano and still hot enough to melt rock, it was a rapidly flowing, hot suspension of poorly sorted ash and pumice particles, and gasses. Pumice is a very light, porous volcanic rock formed when gas-rich froth solidifies rapidly. Some parts of the flow harden before others and get mixed with the advancing flow. Wikipedia has a good Ignimbrite page.

The 2001 report by Gerardo J. Aguirre-Díaz entitled "Recurrent magma mingling in successive ignimbrites from Amealco caldera, central Mexico" provides a technical, in-depth look at the ignimbrite featured here.