Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

entry dated August 24, 2023, issued from near Tequisquiapan, elevation about 1,900m (6200 ft), N20.565°, W99.890°, Querétaro state, MÉXICO

FLOWERING RHINOCEROUS CACTUS

Even more than last year, this year the rainy season has failed to develop. Among cactus species, some which blossomed last year have blossomed only meagerly or not at all this year. Still, so far this year we've had three or four rains during which at least enough rain fell for water to stream downslope, gathering mesquite leaflets into spongy clumps. About five days after such a recent leaflet-clumping rainfall, in a grossly overgrazed, eroded, open area in the scrub, the above Rhinoceros Cactus, CORYPHANTHA CORNIFERA, blossomed. This was the only flowering member of this species I've seen in the wild.

In this area, the worst thing a small, attractive cactus can do is to flower; usually when they call attention to themselves they get dug up by cactus robbers, either to sell or to keep in a pot beside the house. Two days after the above picture was taken, the cactus had disappeared, only a hole remaining.

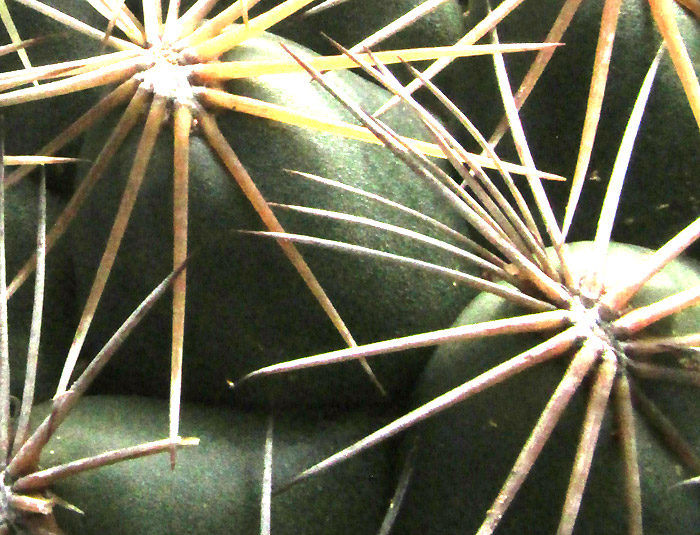

In many cactus species, corollas and stamens arise atop the future fruit, which may or may not be scaly or spiny, as seen on our Cordona Pricklypear page. Above you see that on this species there's no such obvious "future fruit." Also in that picture the distinctive nature of this species' spine clusters is apparent -- maybe 16-18 spines radiating in all directions, with no upward-projecting central spines.

The above close-up better displays the groove indenting the top of each little mound, or tubercle, forming the cactus body's exterior. The presence of those grooves help separate this big genus, Coryphantha, from the other big genus with bumpy, tuberculate bodies, Mammillaria, whose tubercles don't develop grooves.

In the following entry, a trampled, unsaleable Rhinoceros Cactus found last year is documented. There I go into more detail about this species' main field marks, its distribution, and its desperate problem with cactus thieves.

entry dated June 26, 2022, issued from near Tequisquiapan, elevation about 1,900m (6200 ft), N20.565°, W99.890°, Querétaro state, MÉXICO

A SURVIVING RHINOCEROUS CACTUS

When I first began wandering this area seven or eight months ago, the above cactus species was commonly found in overgrazed, much eroded, rocky, abandoned rangeland. About two months ago all the cacti of this species disappeared, with holes left in the ground, apparently victims of the public's demand for cute little potted cacti. This week finally one turned up again, a small, damaged one apparently grazing livestock had stepped on, shown above. Maybe cactus robbers just left this one because of its looks. One reason I'm profiling it is that it may be the last one I see.

Despite its damage and apparent immature, flowerless state, our plant displays important field marks. Mainly, its body is more or less rounded, not flat like the abundant pricklypears. The body is formed not of vertical ridges separated by deep furrows, but rather by hemispherical parts known as tubercles. Some say that cacti with such tubercles look like clusters of chili peppers united at their stems, with their rounded bottoms pointed outward.

Also, the dense cluster of yellowish spines at the top, shown above, indicates that new growth is forming, so there's a potential here for a larger cactus with more hemispherical chili pepper bottoms.

Several cactus genera produce species with such chili-pepper-bottom bodies. Those genera are neatly divided into those with or without a groove, or furrow, extending from each tubercle's spine-bearing areole at the tubercle's tip, downward on the side facing the cactus body's vertical axis. At the right, two damaged tubercles with most of their spines knocked off best show this species' grooves. In this area, that feature alone narrows down the possibilities to just five genera, in the process eliminating the biggest genus of cactus composed of tubercles, Mammillaria.

The remaining five genera are most easily separated from one another by features of flowers and fruits, which we don't have. Using an Internet browser's image-search feature to get general impressions of each of the five genera's form and spine arrangement, we're encouraged to focus on the genus Coryphantha.

Here we're at the center of diversity for the genus Coryphantha. All 45 or so Coryphantha species are native to Mexico, and in our upland central Mexico Bajío region eight species have been documented. Of those species, all bear nectar-producing glands on their tubercles -- extrafloral nectaries -- except two species. Our cactus shows no signs of extrafloral nectaries, so it's one of those two Coryphantha species.

One of those two species produces 6-12 radial spines per spine cluster, while the other produces 12-18. In one of the new-growth clusters I count 18 spines, so that leads to CORYPHANTHA CORNIFERA, endemic just to central Mexico from Zacatecas and San Luis Potosí states south to here in Querétaro, between 1400-2200m in elevation (4500-7200 feet).

Despite occurring naturally in such a limited part of Mexico, Coryphantha cornifera bears an English name because it's much sold commercially as a potted plant -- both robbed and nursery-grown plants. It's often sold under the name of Rhinoceros Cactus. Possibly that name can be explained by the appearance on more mature plants of longer, dark, curving spines at the cactus's top. In the above close-up of the dense cluster of new spines at the body's top, notice in the top, left corner one dark spine beginning to overtop the others, and curving. I'm guessing that that's a rhinoceros's horn. More mature plants bear several such spines, but longer.

Sellers describe Rhinoceros Cactus as able to survive brief frosts, and warn to allow the soil to dry out between waterings, and to provide very good drainage. They advise suspending watering during the winter, which sounds like good avice for a cactus beautifully adapted to our long, rainless dry seasons.