Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

entry dated March 15, 2022, issued from near Tequisquiapan, elevation about 1,900m (6200 ft), ~N20.57°, ~ W99.89°, Querétaro state, MÉXICO

HYBRID CLOAKFERN

As these advanced-dry-season days grow warmer and the landscape becomes ever more parched, dusty and brown-and-gray, the above fern sprouting from the side of rocky ledge is so brittle that it breaks like glass if handled too roughly. The cliff exhibits a geology typical of this area. It's a kind of soft rock, or rock-like compacted dirt, locally called tepetate, composed of an ancient deposition of mingled volcanic ash and sediment from surrounding hills mostly constituted of rhyolite. Up close the fern's pinnae show distinctive features for this species:

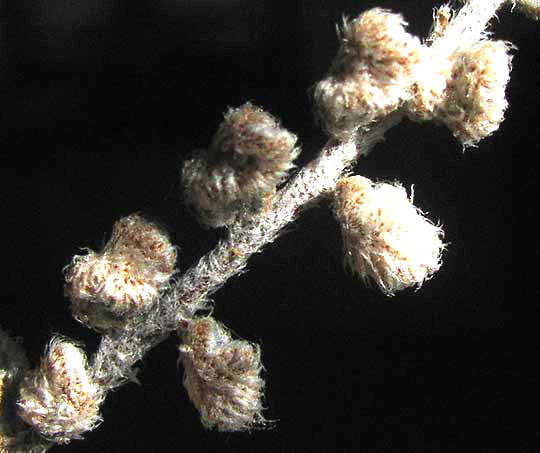

The fronds are so heavily invested in large, silvery, branching and unbranching scales that the plant's surface is hard to see. The picture shows two piannae on a frond. The pinna at the left arises on the frond rachis's far side, so we see the pinna's upper surface. The pinna at the left, arising on the near side, display's its woolly underside. The pinnae's upper sides aren't nearly as woolly as the undersides. On the pinna underside at the right, at least one tiny, brown, spherical, spore-producing sporangium is visible, at the far right, inside the pinna.

The pinnae's small size, about 10mm, and their oval to roundish shape, with hardly any hint of lobes forming, also distinguish this species, helping making it relatively easy to identify. Its English name often is given as Hybrid Cloakfern, the name Cloakfern being used for species of the genus Astrolepis. This is ASTROLEPIS INTEGERRIMA, fairly commonly noticed on deserty, rocky hillsides and cliffs from Arizona to Oklahoma and Texas south into our area in central Mexico. It especially favors limestone areas, though our populations show that it can appear on other substrates as well.

The "Hybrid" part of its name comes from its being a "polyploid" species, meaning that in its cell nuclei three or more sets of chromosomes coexist, having been derived from at least two different species. Normally different species can't reproduce with one another, but polyploids with three or more chromosome sets is common among ferns, with over 95% of fern species being so. However, our Hybrid Cloakfern has been shown to have arisen from a minimum of ten preexisting species. You may be interested in a freely accessible, 1999 online paper by James Beck and others, entitled Identifying multiple origins of polyploid taxa: a multilocus study of the hybrid cloak fern (Astrolepis integerrima; Pteridaceae).

In general, Hybrid Cloakferns in the US have somewhat larger pinnae than ours, and they normally display asymmetrical, shallow lobes.

entry dated June 21, 2022, issued from near Tequisquiapan, elevation about 1,900m (6200 ft), N20.565°, W99.890°, Querétaro state, MÉXICO

The rainy season came late this year. After a shower, the Hybrid Cloakferns expanded to look more fernlike:

Scales on the pinnae's undersurfaces are even more impressive now:

from the December 30, 2012 Newsletter issued from the valley of the Dry Frio River in northern Uvalde County, southwestern Texas, on the southern border of the Edwards Plateau; elevation ~1750m (~5750 ft); N29.62°, W99.86°; USA

HYBRID CLOAKFERN IN MEXICO

In thin, very dry soil between limestone rocks atop a nearby hill there's a dignified, even stately little six-inch tall (15cm) fern that at first you don't see because it's so small and densely invested with silvery hairs that the fronds are whitish, thus well camouflaged among the white limestone rocks and winter's crisp, sunlight-reflecting leaves. Only when you get up close and pay attention do you see its charm, as shown below:

If you examine with a magnifying lens this fern's frond segments, or pinnae, you see that their top surfaces are covered with very unusual white, triangular scales fringed with hairlike teeth, as shown below:

Bottoms of the pinnae are even more thickly mantled with white scales, as shown below:

When you find a fern that's new to you like this, you need to look for clusters of spore producing sporangia -- on frond bottoms the clusters often are called sori, or fruitdots -- because sporangia clusters come in all kinds of configurations, and the configurations vary from species to species, so they make good field marks to help in identification. At first I thought the fronds in the picture were all sterile, but when I looked very closely with lens I saw sporangia, as you can see below:

The sporangia are those reddish-brown, snail-like items almost hidden among the deeply fringed scales on a pinna's undersurface. The seemingly segmented ridges running across the spherical sporangias' tops are special structures helping with spore dispersal. They're called annuluses. When spores inside a sporangium are mature, water inside its annulus's cells or segments drains out causing tension along the annulus's length itself, and across the surface of the sporangium to which it is attached. Eventually the baglike covering of the sporangium snaps open, scattering spores. In this species, each sporangium holds 32 spores. An unusual feature of this species is that its sporangia are not neatly clustered in distinctive fruit-dots on the undersurfaces of the pinnae or inside curled-under pinna-edge margins, but rather haphazardly along the pinnae margins.

The fern's coating of white scales protects its fronds from extremes of sunlight, wind and temperature atop the hill, and reduces evaporation of precious water during long periods of drought. When the fern gets very dry, its pinnae ball up, thus offering less surface area vulnerable to evaporation, as shown below: