Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the February 3, 2013 Newsletter issued from the valley of the Dry Frio River in northern Uvalde County, southwestern Texas, on the southern border of the Edwards Plateau; elevation ~1750m (~5750 ft); N29.62°, W99.86°; USA

STENTOR

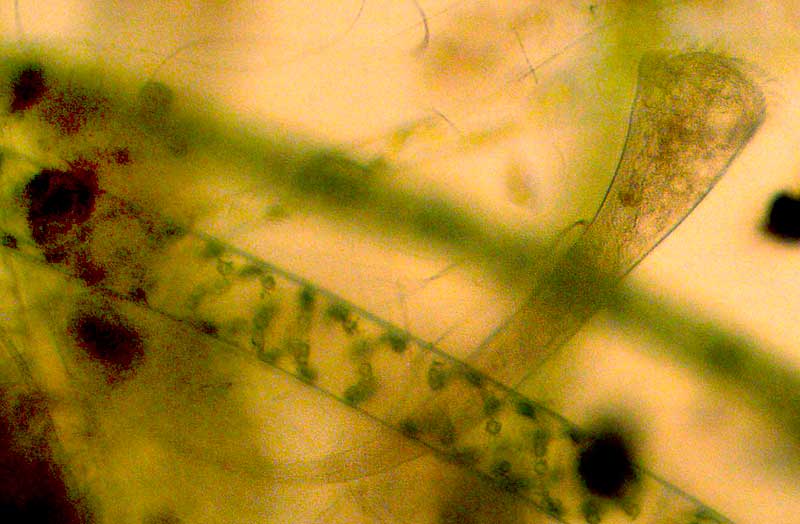

One insight arising from my weekly safaris through drops of water from the little Dry Frio River behind the cabin is that a succession of organisms appears over time. One week a certain species will be abundant, then the next week maybe it'll be rare or not to be seen, while another species not seen before will be most conspicuous. Above you can see the organism observed for the first time this week.

The critter I'm talking about is the curving, slender, horn-shaped one with its head at the picture's upper right. The two dark "bars" extending diagonally across the image are filaments of Spirogyra alga containing spiraling chloroplasts.

The horn-shaped being is one I've been looking for, one of the most famous of one-celled protozoans. That's because of its common occurrence worldwide in freshwater lakes and streams, its unusual and easy to recognize form, and because -- despite its microscope size -- some species of its kind are among the biggest known unicellular organisms. Some species reach 2mm in length (3/16ths inch), though ours was only about half that size.

This is Stentor, the name being both its genus name and the name used when speaking of it in normal English. Stentors belong to the same phylum as the tulip-shaped, cilia-waving Vorticellas we looked at earlier, and behave somewhat like them. That is, you find them rooted to certain spots such as filaments of alga, extending their bodies here and there, the hairlike cilia on their "heads" sweeping food particles into their "mouths." Like Vorticellas, if a Stentor is disturbed or has been stretched out feeding in one spot for awhile, it suddenly contracts into a ball at its "root" and then slowly begins lengthening again, filtering water with its cilia, looking for food as it grows longer. The Stentors I've seen tend to detach themselves every few minutes and swim about until they find a new foothold.

In our photograph, notice the faint, clear, bubble-like items lined up along the lower part of the curving body like a string of beads. That's the macronucleus, typical of ciliate protozoans. A much smaller micronucleus also is present but I can't say which dark spot in the body that would be. The macronucleus is composed of hundreds of chromosomes, each present in many copies, and controls asexual functions such as metabolism. It undergoes direct division without mitosis. Micronuclei handle the organism's sexual reproduction during conjugation, and evolution, and it does undergo mitosis.

The precise way the ciliates' micro- and macronuclei cooperate is still unknown. It's one of those "mysteries of science," as one expert says.

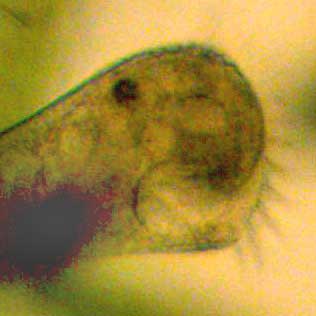

A close-up of Stentor's "head," looking a little like a Walrus's head, is shown above. In that picture the Walrus's whiskers are Stentor's food-gathering cilia, technically known as peristomial cilia. The large, round, bubble-like item that could be the Walrus's open mouth is the contractile vacuole, which through the process of osmoregulation keeps the cell from getting waterlogged. The vague dark spot at the base of the Walrus's nose is the mouth, or buccal cavity. I'm unsure what the black item forming the Walrus's eye is, but it could be a food vacuole.

Mostly Stentor feeds on bacteria and other protozoans.