Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the March 11, 2018 Newsletter with notes from a camping trip on April 2, 2018, in Amistad National Recreation Area 8 miles northwest of Del Rio, Texas; elevation ~369m (~1180ft), N29.465°, W100.964°

FOSSILS IN THE DEL RIO CLAY

Toward the end of the hike from Amistad's Visitor Information Center and Spur 454, the trail climbs briefly onto a low, sparsely vegetated cliff. Layers of bedrock are exposed here, with numerous broken-off, flat pieces of rock strewed across the ground. From the smoothly eroded surfaces of these flat rocks, white fossils emerge in abundance, as on the laptop-computer-size piece shown below:

A close-up of the snail-like fossils is seen below:

Amid these fossiliferous rocks stands a wonderful National Park Service information marker telling us that the surrounding layers of outcropping rock are known as the Del Rio Clay. This clay and its fossils were deposited during the Cretaceous Period, about 100,000,000 years ago. The marker even bears a drawing of a spiraling, snail-like fossil shell looking like those in the above pictures, identifying them as members of the extinct genus Ilmatogyra, formerly classified as Exogyra. The USGS page describing the Del Rio Clay lists Exogyra arietina as an abundant megafossil in the unit, so a good guess is that that's the species in our rocks, possibly now shifted to the genus Ilmatogyra.

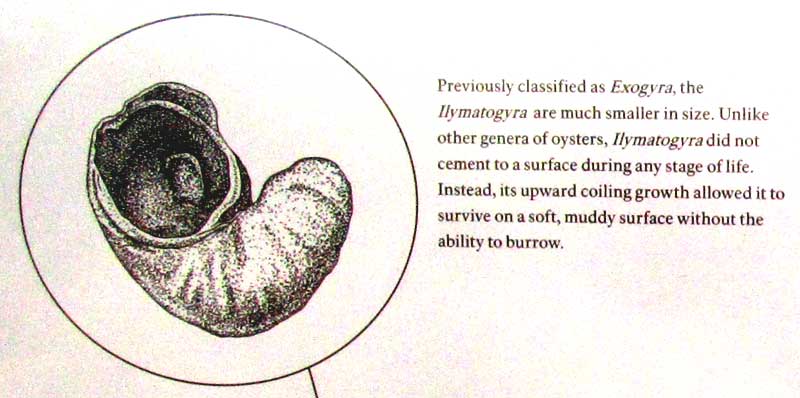

A picture of the marker's drawing of this fossil, and text accompanying it, is shown below:

Despite the fossils' snail-like looks, they're not snails or even closely related to snails. They are indeed mollusks, like snails, but the Mollusk Phylum is divided into three main subdivisions, or classes: bivalves such as clams and oysters; cephalopods like the octopus, and; gastropods like snails and slugs. Our marine Cretaceous fossils are bivalves along with clams and oysters.

In fact, our fossils belong to the Oyster Order, the Ostreoida, and within that, the Gryphaeidae Family, often known as the foam or honeycomb oysters. Since oysters are bivalves, they have two shells, not one as with snails. Looking at our pictures, I see nothing that might be the second shell. However, the marker's drawing of a Del Rio Clay fossil shell shows a kind of thumbnail-like appendage at the top, left, so maybe that's the second shell. I read that species in the Gryphaeidae are "inequivalve" -- the two shells being unlike one another. The left, lower shell is convex, while the other is flat or slightly concave.

The Cretaceous Period during which this bivalve lived came to an abrupt end when about 65,000,000 years ago a six-mile-wide object (10 km) struck the ocean where the Yucatan Peninsula now exists, killing off the dinosaurs, and nearly half of all marine genera. Is that what caused our Del Rio Clay oysters to go extinct?

Isn't it something to think of a kind of living thing that once was as abundant as our fossil species obviously was, so suddenly simply disappearing from the face of the Earth -- a whole kind of being obliterated and leaving no descendants? Might not the same happen to us humans?