An Excerpt from Jim Conrad's

NATURALIST NEWSLETTER

June 21, 2018

Issued from Rancho Regenesis near Ek Balam ruins 20kms north of Valladolid, Yucatán, MEXICO

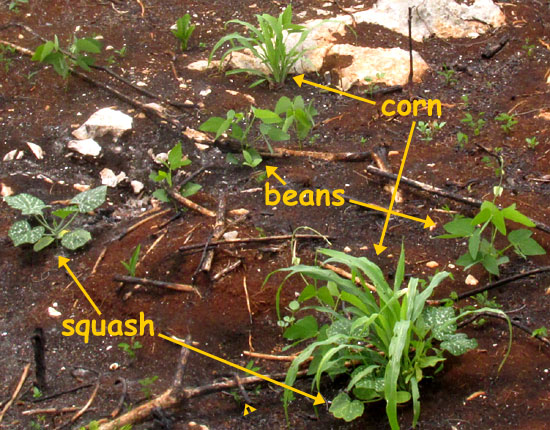

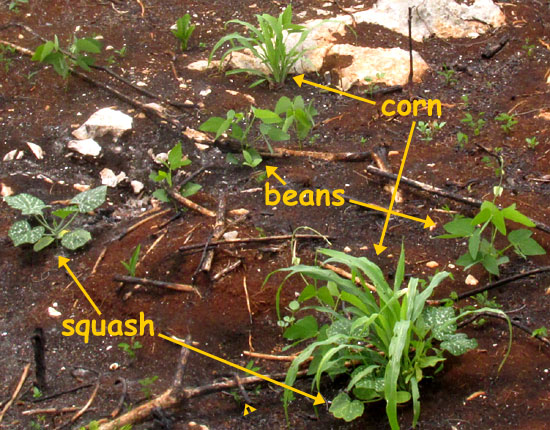

A milpa is a traditional indigenous American cornfield in which bean vines and ground-running squash are interplanted with corn, the bean plants returning nitrogen to the soil, and the squash's big leaves shadowing the soil, helping it retain moisture. Milpas, are planted in forest plots opened up by slash-and-burn clearing and are productive for three to five years or so, until weeds, insects and diseases move in. Then the plots are abandoned, the forest grows back, and eventually is slashed and burned again.

Mayan milpas are only a fraction as productive as North American cornfields using chemical fertilizers, pesticides and hybrid, often gene-manipulated seeds. However, milpa farming has sustained the Maya for thousands of years and, at least at low population densities, has proved to be sustainable.

Still, nowadays few milpas in this area produce their potential output because mostly they're planted in order to receive a government subsidy. Milpa farming is hard work, chancy, and people like to eat other things than home-cooked corn products, beans and squash. Young Maya are somewhat embarrassed to be seen working in a milpa. In this area, at the end of each milpa growing season, most milpas are so neglected that they're choked with weeds, and large numbers of raccoon-like coatis, and birds such as Yucatan Jays, take much, most or all of the produce.

However, on the road between the rancho and the village of Ek Balam there's a milpa planted he old way, with interplanted corn, beans and squash. Last month an old man could be seen there poking holes in the ground with his stick, taking seeds from his sidepouch, dropping them into his holes, and covering them with his foot. Nowadays his crop is coming up. At the top of this page you see the field and a close-up of part of it.

The old man's textbook traditional milpa is so unusual that when I bike by his field and he's out there working, I wonder what he's thinking and feeling. What causes him to spend mornings in his milpa when other men in the village are doing other things, or producing milpas only in name, for the subsidy payment?

I like to think that he's out there because he's obstinate, just won't give in to the new changes, and doesn't care what his neighbors think. I like to think he's figured out that the way the world and humanity are going is all wrong, that he doesn't want any part of it, and that he's decided that if he's going to do anything at all, he can't do better than plant seeds in the ground, whether or not his family will eat his corn, beans and squash.

The old man's situation is worth thinking about because all the rest of us also are facing profound social, political and economic changes coming on fast. Right now civilization is at a threshold at which robots and computer algorithms are poised to begin doing nearly all the work of humans, and doing it cheaper and better. What's to happen to us when nobody want to pay for our work, and we don't even have milpas for growing food?

Maybe the old man in his milpa offers us at least part of a strategy for dealing with these times, even if we're unable to produce a milpa. Here are the strategy's main points: