Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the the June 24, 2012 Newsletter issued from the woods of the Loess Hill Region a few miles east of Natchez, Mississippi, USA

DUCKWEED

Standing waters in local bottomland drainage ditches nowadays are green-carpeted with tiny, oval, flat plant bodies which most folks recognize as duckweeds. Thing is, in North America four or five genera of plants known as duckweed are found, and many more species. The fun is in figuring out which duckweed you have.

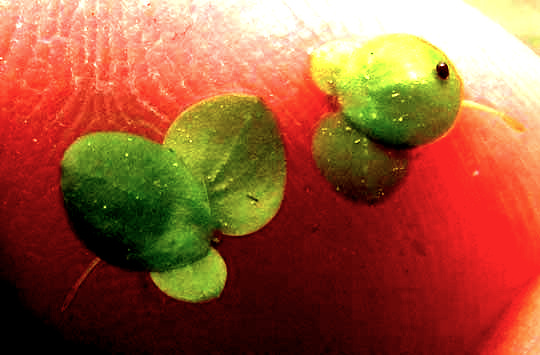

A close-up of a tiny section of a local duckweed-covered drainage ditch is shown above. In that picture the parsley-like items emerging from the water are aquatic, invasive Parrotfeathers, which we looked at a while back. On the water's surface you can see that two duckweed species intermingle, a smaller, paler one and a larger, darker-green one. Right now we're focusing on the big one, whose bodies, or fronds, are mostly 6-8mm long (¼ inch). Some of those larger ones adhere to my fingers below:

Notice how often one frond appears to be attached to one or more others. That's because -- even though these are flowering plants who can reproduce sexually -- mostly they reproduce vegetatively, with new fronds "budding" from older ones. Also notice that veins originating from little depressions at the fronds' bases are vaguely visible, maybe seven or so in the larger ones. A view of the undersides showing several roots emerging from the point that appears as a depression on top is below:

Most duckweed species in our area are members of the genus Lemna, but plants in that genus bear only one or no root on the lower surface. Spirodela has several roots. The Flora of North America lists two Spirodela species for North America. Our plants' five or fewer roots and five to seven veins key it out to SPIRODELA PUNCTATA*, occurring nearly worldwide, and introduced into North America, where mostly it's found in the southern states. Some experts place the species in another genus, calling it Landoltia punctata.

With names like duckweed and duckmeat, this species' importance to ducks and other waterfowl is obvious. It's also important to fish and invertebrates who live in the duckweed community. Even humans are becoming excited about duckweed. The page at http://www.duckweed49.com suggests that "Duckweed may be the most promising plant for the twenty-first century... "

Mainly that's because duckweed produces more protein per square meter than soybeans. As such, it can be used to feed fish, shrimp, poultry and cattle. Also, duckweed can purify and concentrate nutrients from wastewater such as sewage.

from the April 6, 2014 Newsletter issued from the Frio Canyon Nature Education Center in the valley of the Dry Frio River in northern Uvalde County, southwestern Texas, on the southern border of the Edwards Plateau; elevation ~1750m (~5750 ft); N29.62°, W99.86°; USA

DUCKWEED IN UVALDES WATER RECYCLING PONDS

On Uvalde's south side, ponds have been dug for recycling the town's used water. The area consists of interconnected ponds separated by tracts of arid scrub, and has been designated as Cooks Slough Sanctuary & Nature Park. It's a pleasure to walk among the ponds spotting waterfowl and, right now, smelling the heavenly fragrance of flowers of Huisache, or Sweet Acacia, currently at their peak of flowering and looking like elephant-size, yellow-orange bouquets.

Despite the abundance of ducks, these days there's only a little duckweed -- those green, oval, tiny, aquatic plants that float atop certain quiet bodies of water, like green confetti. Below, you can see some at a pond's edge:

Several duckweed species might be found in our area, so naturally it's good to know which one this is. The ID process began by getting some plants onto my fingertip, shown below:

The first decision to make is whether this is the main duckweed genus, Lemna, in which many species are found, or another, smaller genus. To settle this first issue, one important field mark to notice is the number of veins in each frond. In these plants the veins are faint, only three per frond showing plainly, but if you study closely, assuming that veins occur in the fronds' bottom sections where no veins are visible, you might decide that at least seven to nine veins are present. Fronds of the main duckweed genus, Lemna, normally have only one to five veins, rarely seven, so this is a hint that we have something other than Lemna. Below, the plant shows another important field mark. You can see it below:

The whitish, hairlike items are roots that dangle into the water. Lemna fronds produce only one root per frond. This frond has five or six, so this must be something other than the common duckweed.

The Flora of North America recognizes four genera in the Duckweed Family, the Lemnaeae. Plants in two of those genera produce no roots at all, so if we don't have Lemna, that leaves just one duckweed genus, that of Spirodela. Our plants with their five to seven veins, and five or so roots key out to SPIRODELA PUNCTATA(but probably S. polyrhiza).