Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the November 18, 2012 Newsletter issued from the valley of the Dry Frio River in northern Uvalde County, southwestern Texas, on the southern border of the Edwards Plateau; elevation ~1750m (~5750 ft); N29.62°, W99.86°; USA

BALL MOSS FRUITING

In Mexico we saw lots of bromeliads -- those epiphytes (plants living on other plants but not necessarily parasitizing them) that form such a beautiful and interesting element of tropical American vegetation, often creating veritable airborne gardens on the limbs of larger trees. In the Temperate Zone, bromeliads are often cultivated as potted plants, but few species can handle cold weather. One bromeliad that makes it as far north as the US Deep South is Spanish Moss, which is an unusual bromeliad not only because it can stand some freezing, but also because it forms dangling strands of connected plants. The vast majority of bromeliads are tufted plants looking like individual small agaves. Bromeliads are such a unique group of plants that they have their own Bromeliad Family, the Bromeliaceae, harboring over 3000 species.

Spanish Moss occurs in Eastern Texas, but here in the southwestern part it's too arid for it. A few miles south of here someone has strung Spanish Moss in their trees, and it's survived there for several years, but it hasn't spread to other trees, and I've never seen it on other trees in the region.

However, we do have another native bromeliad species here and it's abundant. People call it "Ball Moss," which is unfortunate because mosses reproduce by spores while bromeliads are flowering plants. Ball Moss is TILLANDSIA RECURVATA, a member of the same genus as Spanish Moss, Tillandsia usneoides. These two relatively cold-tolerant species are very closely related. You can see one of our typical Ball Mosses on a tree's dead branch near the cabin at the top of this page.

We've run into this bromeliad before. In arid north-central Mexico, in Querétaro, we often saw it growing thickly on power lines, as shown in the next section.

Ball Moss occurs in South America up through Central America, the Caribbean and Mexico, into the US states of Arizona, Texas, Louisiana and Georgia.

Nowadays our Ball Mosses are fruiting. In the above picture the slender stems arching from the tuft of plants bear cylindrical capsules that are splitting open now, releasing seeds. The seeds are equipped with long hairs to help with wind dissemination. Below you can see a split-open capsule with its fuzzy contents, with slender brown seeds at the top of several tufts:

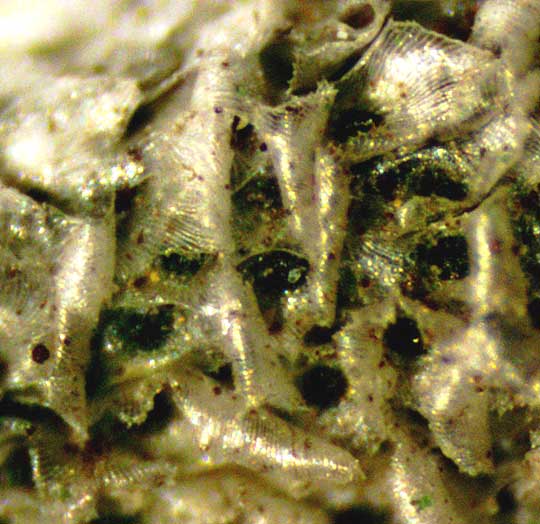

I was curious as to what Ball Moss's gray, crusty surface might look at high magnification, so I looked with our dissecting scope, and you can see what I saw below:

Ball Moss's surface is well protected by an armor of silvery, overlapping scales. This may help explain the species' relative tolerance of cold weather.

In a recent Newsletter I mentioned that many landowners in this area despise one of the two dominant natural trees here, the Ashe Juniper, believing that it's an invasive that sucks water from the ground. Many landowners uproot and burn as many Ashe Junipers as they can, often at great expense, feeling that they are providing a public service. I've addressed the situation on our Ashe Juniper page at http://www.backyardnature.net/n/w/ashe-jun.htm.

A similar situation exists with regard to Ball Moss. In minds of many property owners here, if you have trees full of Ball Moss, you're negligent in controlling an awful pest that's killing our shade trees. They say you need to spray your trees to kill the Ball Moss. Often Kocide 101, a fungicide, is recommended for "infestations," but around here most people just spray a mixture of water and baking soda.

The reason people don't like Ball Moss is because often they see what's shown below:

That picture shows an Ashe Juniper with healthy, green foliage on the left, which is Ball Moss free, while on the right the dead branch is absolutely choked with Ball Moss. Therefore, Ball Moss killed the branch.

The other way of looking at it is that in this droughty area large tree branches are always dying back when the rains fail, as they have been lately. The dead branches devoid of leaves provide a perfect habitat for Ball Moss, which moves in quickly and aggressively.

Large colonies of Ball Moss do shade a tree's lower branches but if the Ball-Moss-filled branch bore the tree's own foliage, the shade wouldn't be much more. Ball Moss does sometimes encrust a stem so thickly that new tree shoots hardly have a place to form. However, Ball Moss "infestations" occur on weak, dying or dead branches, so there's not much competition there between sprouts and bromeliads.

Whatever the reasoning, the people I've spoken with just won't believe that Ball Moss is anything but an ugly pest needing to be exterminated or at least "cleaned" from trees around the house.

When I was student we learned that bromeliads neither hurt nor help the trees they populate. However, now it's clear that they do contribute to the environment they occupy, like all natural organisms. A 1994 study in the Canadian Journal of Botany {72 (3): 406-8} found that our very own Ball Moss harbors the nitrogen-fixing bacterium Pseudomonas stutzeri. Ball Moss helps the tree it's living on by converting nitrogen in the air, which is unusable to flowering plants, into a usable nitrogenous compound the plant can't live without. When Ball Mosses fall onto the ground, which they do constantly, they're "fertilizing" the soil around their host tree with a nitrogenous, organic substance -- their own bodies.

So, droughts weaken our local trees, causing certain branches to die. Mother Nature sends in Her first responders, Ball Moss, whose job it is to fertilize the tree with nitrogen. But people wanting to help their trees kill the Ball Moss.

Here is an individual Ball Moss plant separated from its "ball" on a tree. The handlike item at the top right shows split-open capsular fruits that have split open, the hair-topped seeds disseminated by the wind.

from the January 12, 2007 Newsletter issued from Sierra Gorda Biosphere Reserve, QUERÉTARO, MÉXICO

BROMELIADS ON POWER LINES

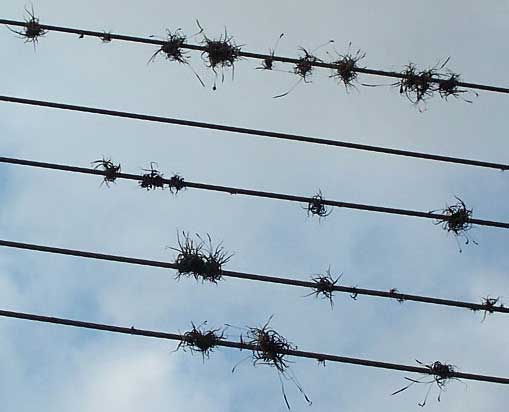

Travellers in the tropics know very well the phenomenon shown below:

That picture is of bromeliads growing naturally on power lines here in Jalpan. The bromeliad is TILLANDSIA RECURVATA, sometimes called Small Ballmoss, though it's a bromeliad, not a moss. As you might expect with a species that can grow on power lines, this is a tough little plant with an enormous distribution throughout tropical and part of subtropical America. It's found from as far north as Georgia and Arizona south to southern South America. I've even seen it growing on cactus spines and barbed-wire fences.

Seeing Tillandsia recurvata on power lines should dispel any suspicions you might have that epiphytes -- plants growing on other plants and elevated structures -- have to be at least a little parasitic on their hosts to survive.

The vast majority of epiphytes aren't parasitic at all. They just grow epiphytically because they need a place to live and their perches give them access to light. Though the percentage is much less in temperate climates, when the whole world's seed plants and ferns are considered, about 10% of them are epiphytes. Over half of the Orchid Family's 20,000 species are epiphytic.

Whenever you read how epiphytes manage to survive you find a great deal about dust, trapped organic debris accumulating around plant bases, and trickling rainwater, but there's little said about microorganisms. Recently studies have shown that in many epiphytic species bacteria play a huge role by fixing atmospheric nitrogen. Almost all orchids have mycorrhiza associated with their roots which provide the plants with micronutrients. Our little Tillandsia recurvata has been shown to have its blade surfaces populated by the nitrogen-fixing bacterium called Pseudomonas stutzeri.

So here's more evidence that we underestimate the importance of microorganisms in our lives, and to Life on Earth. We've already spoken of how very much the health and survival of animal species -- humans being animals -- depend on a diverse, well balanced population of bacteria being present in our guts.

Sometimes I think that future generations may regard the manner in which we abuse the planet's microorganisms as even more disastrous than how we deal with global warming and nuclear proliferation. When we clear-cut a forest and cause so much erosion and oxidation of the soil's organic content, that's devastating on the established bacteria. From the regenerating forest's point of view, loss of a healthy community of bacteria may be worse than losing normal soil structure and the forest's self-regulating microclimate.