Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the September 30, 2012 Newsletter issued from the valley of the Dry Frio River in northern Uvalde County, southwestern Texas, on the southern border of the Edwards Plateau; elevation ~1750m (~5750 ft); N29.62°, W99.86°; USA

HUMMINGBIRD MIGRATION MYSTERIES

You should see the circus all day long at my host's hummingbird feeders. In southern Texas the peak of hummingbird fall migration occurs around the first day of autumn, and nowadays if you can identify most of the birds at a typical feeder here -- with all the similar-looking females and the juveniles in various intermediate plumage phases buzzing around too fast to notice much about them -- you're a better birder than I. In fact, except in the rare case of having a mature adult male in summer plumage, to identify nearly all of what I see here I must photograph them, get the picture onto my laptop screen, then do a lot of studying in field guides. For example, this week I shot the picture at the top of this page.

Unlike most at the feeder, that bird at least has the beginning of a splotch of a red throat, so the possibilities are much reduced. The lack of rusty coloring on the chest and back also limit the possibilities. The other definitive field mark is the tail, which is somewhat forked.

For me the question is whether this is a Ruby-throated or Broad-tailed Hummingbird. I'm told that Broad-tails are the most common here, outnumbering Ruby-throats, which are only migrants, ten to one.

However, after comparing many pictures on the Internet with our image I'm thinking this is a migrating Ruby-throat, because Broad-tailed Hummingbird tails are rounded, not forked. I read that male Ruby-throats begin moving through Texas the first week in July, then females and juveniles follow in August and September. If anyone out there disagrees with the ID, let me know.

from the August 8, 2004 Newsletter, issued from near Natchez, Mississippi, USA:

SPIDER-EATING HUMMINGBIRD

Friday morning I saw that overnight a spider had constructed a very elegant little web among my beanpoles. I went looking for the spider but found that it was neither in its web nor on the surrounding poles. I was wondering what had happened to it when a hummingbird suddenly appeared on the other side of the web just inches from my face, and very deliberately examined the web's center. I think the bird had just breakfasted on the spider I'd been looking for, and he'd returned to see if there might be another.

Hummingbirds do occasionally eat small critters like spiders and gnats, especially females during nesting season. If you think about it you can understand why. Sugar-water in peoples' feeders contains only the elements hydrogen, oxygen and carbon. Flower nectar has other components, but it's also mainly hydrogen, oxygen and carbon. Yet every nucleus of every cell of every living thing on Earth must contain some phosphorus, because DNA, the molecules in which our genetic code is incorporated, has a sugar-phosphate "backbone." The amino acids attached to that "backbone" can't exist without atoms of nitrogen. There's a lengthy list of other elements just as absolutely necessary for the most basic life processes. No living thing can survive for long on a diet consisting of nothing but hydrogen, oxygen and carbon, no matter how many calories that diet provides.

The little hummer who came looking into the spiderweb was a juvenile, so his cells were dividing like crazy, his glands producing complex hormones, and I'll bet his body was just screaming for nitrogen, phosphorus, magnesium and a host of other essential elements. And I'll bet he was disappointed to find that only one mineral-rich spider had been responsible for that nice web.

from the August 17, 2006 Newsletter, issued from Polly's Bend, Garrard County, in Kentucky's Bluegrass Region, USA:

AN ANNOYED HUMMINGBIRD

At dusk this week I was drawn from my reading by a loud vibrating sound. The noise was so loud and deep-toned that the notion that it might be a hummingbird didn't occur to me. Yet, such was the case. Nearby a Ruby-throated Hummingbird was expressing himself to a Blue-gray Gnatcatcher cowering among some privet leaves.

The hummer emitted his buzz while pointing his beak directly at his enemy and performing quick U-shaped, pendulum-like flight-oscillations. During courtship, male Ruby-throats perform such "pendulum flights" on a larger scale, with the U's arms being several feet across, but these Us were only a few inches wide, each swing accomplished in only about a second.

How did such a little bird make such a big noise? I'd guess it was just by rearranging his feathers and beating his wings faster and/or harder, but I can hardly imagine his wings sustaining such abuse.

After about 7 seconds of being very loudly threatened the gnatcatcher flew to a nearby Rose-of-Sharon where the entire performance was repeated. The gnatcatcher lasted about 5 seconds there, and then flew to another bush, and when the hummer arrived there the gnatcatcher fled across the yard, leaving the area completely. Then the hummer immediately commenced visiting the Rose-of-Sharon, humming his usual way.

Though I've witnessed many hummingbird displays, this was my first time for this one. I can understand why a hummer wouldn't like a gnatcatcher because they both grab gnats from the air. But I would say that a hummer would have to consume a great many gnats to fuel the loud humming I heard that day.

from the April 18, 2004 Newsletter, issued from near Natchez, Mississippi, USA:

HUMMINGBIRD NEST

The highlight of Friday's birding walk came during my cornbread break at the Woodland Pond when I noticed a female Ruby-throated Hummingbird darting around. She was so fast it took me a while to catch on to what she was doing. She was building a nest.

Books tell us that only the female works on the nest, and it usually takes her 6-10 days. First she builds a flat base of thistle and dandelion down. Around here dandelions are fairly rare but thistles are frequent. This base is positioned on the upper side of a branch and attached with spider webbing. Nest walls are made with "white plant down," bud scales, spider webbing and sometimes pine resin. The exterior is decorated and camouflaged with lichen.

My hummingbird's nest was typically located. It was on a straight twig overhanging the pond, as thick as a ballpoint pen and descending at a 45° angle. The nest was about six feet above the pond's water and some 10 feet from the bank. The tree was a Red Maple and the nest, about the size of a walnut, was nearly completely hidden by a single maple leaf. The nest looked almost finished, for already it was adorned with gray lichen.

from the July 6, 2006 Newsletter, issued from Polly's Bend, Garrard County, in Kentucky's Bluegrass Region, USA:

HUMMINGBIRD EGGSHELL

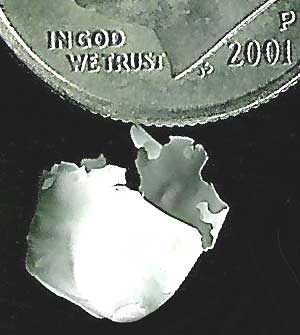

Ruby-throated Hummingbird nests I've seen have all been on down-pointing tree limbs over water. Therefore I was surprised the other day when I was passing before Ruth's garage on my way to connect to the Internet and half of a hummingbird's eggshell fell onto the pavement at my feet. You can see that very shell next to a dime for size comparison at the right.

Ruby-throated Hummingbird nests I've seen have all been on down-pointing tree limbs over water. Therefore I was surprised the other day when I was passing before Ruth's garage on my way to connect to the Internet and half of a hummingbird's eggshell fell onto the pavement at my feet. You can see that very shell next to a dime for size comparison at the right.

The image shows only half of a shell. You can clearly see the jagged cut made by the hatchling inside the shell as it twisted around, ripping at the egg's equator. Typically a baby bird is equipped with a sharp "egg tooth" atop its beak with which it cuts its way from inside the egg. Upon hatching, the egg tooth falls off.

Once I thought about it, I realized that the nest's location wasn't as unusual as it might seem. In this land of karst topography with precious little standing water, in every way the hummer had stuck to the standard concept of what makes a good hummingbird nesting site -- except that flat-surfaced water had been exchanged for flat-surfaced asphalt!

It was interesting that the eggshell had been discarded so near the nest, for I've seen birds carry shells far away. Birds remove empty shells from their nests so that the shells won't attract predators. This fact was proved in a series of classical experiments conducted by pioneer ethologist Niko Tinbergen, who worked largely with gulls. You can read about it at http://www.stanford.edu/group/stanfordbirds/text/essays/Empty_Shells.html.

from the January 3, 2016 Newsletter issued from Hacienda Chichen Resort beside Chichén Itzá Ruins, central Yucatán, MÉXICO

RUBY-THROATS OVERWINTERING IN THE YUCATAN

By placing leg bands bearing unique numbers on a large number of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, it's been shown that in the spring up north often specific individual birds arrive at the same feeder on the same day for years in a row. Some folks get attached to their hummers, so they might be gratified to know that this winter the Yucatan is buzzing with Ruby-throats just waiting until they can return back north. One morning this week one that seemed especially interested in this human sat on a branch nearby watching me and preening his feathers in the early morning sun, shown below:

Here at Hacienda Chichen in the north-central Yucatan Peninsula we can look for these hummingbird species: Canivet's Emerald; White-billed Emerald; Buff-bellied; Cinnamon; the Ruby-throated Hummingbird, and other species who come up sporadically from the south. So, with immature and winter plumages involved, how can we be sure this is a Ruby-throat? Several species display immature and female plumages very similar to our bird's, especially those of the Black-chinned Hummingbird.

Mainly, the species most likely to be confused with Ruby-throats don't occur in the Yucatan. Also, our hummer's beak is notably shorter and straighter than in many species, and it's black, not red. The white spot behind the eye -- the "postocular spot" -- is right for a female or juvenile bird, plus Howell writes that the immature male Ruby-throat bears lines of dusky flecks on the throat, and they are very conspicuous on this individual.

In the US Deep South often individual Ruby-throats remain in the area late in the season, and even survive freezing temperatures. If Ruby-throats are that good at dealing with the cold, why don't more remain up north instead of making the dangerous flight to down here? One small population does permanently winter in the Outer Banks of North Carolina. The experts at Hummingbirds.net explains that all hummingbirds are carnivores -- nectar is just the fuel they use to power their flycatching activities -- and that they depend on insects that are not abundant in subfreezing weather. Most hummers must migrate south to "home" in the American tropics, or risk starvation.

At http://www.hummingbirds.net/migration.html you can read lots of interesting details about Ruby-throat migration. Another point made there is that during spring migration some birds may follow the Gulf Coast northward on a longer but safer route to North America, but many who overwinter between southern Mexico and Panama take a straighter route through the Yucatan, gather on the northern coast gorging on insects and spiders to build up fat, and, when the weather seems to be OK, usually at dusk, launch northward into the open sky, nonstop, for up to 500 miles, taking 18-22 hours, depending on the weather.

When you're on the northern coast seeing how tiny these birds are, and how vast and imposing the sky out over the Gulf toward the north usually looks at dusk, you just have to be amazed.