Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

Issued March 19, 2020 from the forest just west of Tepakán; elev. ~9m (~30 ft), N~20.053°, W~89.052°; central Yucatán state, MÉXICO

HONEYBEE UP CLOSE

Below you see a honeybee drinking water from a pan set outside just for this purpose. Here it's the heart of the very hot, dry season, and beekeepers tell me the hives need the water.

from the May 5, 2008 Newsletter written in the community of 28 de Junio, in the Central Valley 8 kms east of Pujiltic,

elev. ~700m (2300ft), ~N16.331°, ~W92.472°; southeastern Chiapas state, MÉXICO

HONEYBEES COLLECTING CORN POLLEN

Here on irrigated land crops can be grown year round, so cornfields appear in all stages of development. The other day I passed by one field with tasseling corn and heard a prodigious numbers of honeybees. They were gathering pollen from the corn's male flowers, as seen below:

In that picture notice the yellow gobs of pollen on the bees' hind legs. If you're unsure about what corn tassels are and what kind of flowers you're seeing in that picture, check out the corn-flower anatomy page at http://www.backyardnature.net/fl_corn.htm.

I had mixed feelings about seeing all those bees. On the one hand it was awe-inspiring to experience such phenomenal, single-minded activity going on in Nature, but on the other I had to remember a recent visit a government bee-specialist made to the community, to help us produce more honey. I'd asked what the effect was on bee colonies of all the pesticides used here, especially in the sugarcane fields adjacent to the community.

"It's awful," the man said, and then he further volunteered, "It's not just the bees, but everything living. There's a crises all through the sugarcane region because of all the tumors and cancers people are turning up with."

After a moment of silence, stunned by the visitor's candor, I asked if there was a problem with bees in areas like ours producing pesticide-contaminated honey.

"Honey from this area is absolutely pure," he said. "When a bee encounters insecticide, it simply doesn't make it back to the hive."

That day when I saw all the bees gathering pollen from the corn, the odor of freshly applied chemicals hung heavily in the air, stinging my nose and producing a cottony sensation in the back of my mouth. The corn tassled, the bees hummed and all seemed right with the world, but, maybe not...

from the July 31, 2011 Newsletter issued from written at Mayan Beach Garden Inn 20 kms north of Mahahual; Caribbean coastal beach and mangroves, ~N18.89°, ~W87.64°, Quintana Roo state, MÉXICO

SARA'S HONEYBEE

Sara in Washington State was wondering about the honeybee in last week's Newsletter trying to pry into the Coconut Palm flower, shown below:

Once I thought about it, Sara was right to wonder about a honeybee here, because this wouldn't seem like an appropriate place for them. First, honeybees are invasive species introduced from Europe and in our immediate area no one is keeping hives of them. If wild colonies have become established in trees here along the coast, surely 2007's Hurricane Dean would have destroyed them, as it did so many other forms of wildlife.

It turns out that one of our managers here, my Maya friend Martín, runs a beekeeping business on the side, so I asked him about honeybees showing up here on the beach 20 kms north of Mahahual.

"It' a little surprising to see European honeybees here," he said. "However, a man in Mahahual used to keep them and some must have become established up here. The man's colonies gradually disappeared, some getting sick and dying, in others the bees just flying away. The big problem here is that there's just the mangroves and this narrow sand rise along the beach, and there aren't many kinds of plants in these places. There are times of the year when there's just nothing producing much pollen or nectar."

Martín also told me that around here practically all honeybees are "Africanized" -- what several years ago movie producers called "killer bees." But beekeepers are content with their new easy-to-antagonize bees because "Africanized" bees produce far more honey than traditional European honeybee types.

from the January 23, 2005 Newsletter issued from Hacienda Komchén de Los Pájaros just outside Dzemul, Yucatán, México

HONEYBEES IN THE TOILET

This week we also had honeybees in the deposit part of a seldom-used toilet behind one of our bungalows. Lino the hired hand first went to see if he could get rid of them, but when he saw that it was a large colony he came back and said we should call a beekeeper in town to come get them.

So one afternoon Dzemul's bee-man, Don Graciliano, and his helper came on a motorbike, to get the bees. I'm used to seeing beekeepers using lots of equipment and wearing fancy veils and suits, so when I realized that these two fellows and all their gear had come on one small motorcycle, I figured we had a couple of amateurs.

They quickly proved that surmise wrong. Without veils or gloves they simply puffed some smoke onto the exposed combs, and went to work. They'd cut a comb loose (waferlike with hexagonal, honey-filled cells, maybe 15 inches across and one inch thick) and either deposit it along with its crust of bees into his wooden hive, or else he'd brush off the bees and put the comb into a container, for later eating. When he worked deeper into the hive and couldn't see well he pulled out some gloves. He had had gloves all along but hadn't bothered with them! Really it was amazing to see these two guys working inside a frantic cloud of bees, not being stung.

When they were finished, Don Graciliano had a healthy new hive of bees and a good bit of honey, and we had some honey, too, with a nice flowery taste.

"See, it's easy," Don Graciliano said as he walked away.

"It's art," I replied, in admiration.

from the February 19, 2012 Newsletter issued from Hacienda Chichen Resort beside Chichén Itzá Ruins; limestone bedrock; elevation ~39m (~128ft), N20.675°, W88.569°; central Yucatán state, MÉXICO

A PUDDLE OF BEES

South of Pisté I took a little dirt road off the main highway, just exploring. About a hundred yards inside the woods honeybees were buzzing. I looked all around and finally saw on the ground below me what's shown below:

When bees swarm they do so in much greater numbers than that. Sometimes smaller "afterswarms" take place, but they're larger, too. I guessed that here I was seeing drones competing to mate with a new queen on her way into the world to found a new colony.

However, once I was on my belly looking closely, it was apparent that these weren't drones; they were female worker bees. Drones are larger, their middle body section (thorax) is nearly as large as the rear section (abdomen), and their compound eyes are joined. With this discovery I issued an involuntary "Ha!" which apparently I do habitually when I discover something. The little puff of hot air accompanying that "Ha!" was my undoing.

For, instantly several bees darted at my face and one stung me on a cheek. I've done lots of bee watching, though, so I just stayed very still, let them settle down, and watched, trying to figure out what was going on. A few minutes later several bees out of nowhere began circling my head, buzzing more loudly than you'd expect, and even though I remained very still one got me on the forehead. Other bees entangled in my beard until I broke my stillness and combed them out.

For me this was strange behavior so I figured I'd better get away. Calmly I walked a few feet but the swarm followed me, clearly upset. As I've always done in such cases, I draped a bandana over my head, sank to the ground, and just lay there quietly until they went away. They did leave, but only after buzzing around much longer than I'd expected.

In a few minutes I was about to get up when a bigger squadron than before arrived, behaving and buzzing even more threateningly. One got beneath the bandana and stung me behind the ear. Others clustered atop the bandana, sometimes dive-bombing and bumping against it. Eventually I realized that when I exhaled they got angrier. Finally they went away.

Five minutes later another wave came, larger and yet angrier and this time I got it on the arm and, when the bandana slipped off, on the forehead over an eye. I just lay there, the bandana covering my face, gradually realizing that a trend was shaping up in which I was visited by ever larger, ever angrier swarms. My old strategy wasn't working.

And then it occurred to me: These were not the bees I grew up with. These were "Africanized bees," what some call "killer bees." What if I were near hives with thousands of them... ? I peeped from beneath my bandana, looked around and, sure enough, through the scrub the white of painted hives showed up about 30 meters away.

I stood up, was surprised to not be attacked as I walked briskly to the bike, mounted the bike and left as fast as I could, getting stung only twice more as I passed the little cluster still on the ground, and even still I don't know what the ground ones were up to.

from the February 19, 2012 Newsletter issued from Hacienda Chichen Resort beside Chichén Itzá Ruins; limestone bedrock; elevation ~39m (~128ft), N20.675°, W88.569°; central Yucatán state, MÉXICO

STINGERS LEFT BEHIND

When honeybees sting, normally their barbed stingers get caught in the skin harpoon-like, so the bee can only fly away by literally ripping the rear-end of her body apart, which she does. The honeybee then dies.

The bee's rear end remains atop the stinger stuck in the victim's skin. You can see a stinger sticking from my skin (inset at left) and the same stinger extracted and resting on my fingertip (at right) below:

Part of the white, cellophane-like material atop the extracted stinger is a sac of venom, which continues pumping venom into the sting for about a minute after the bee departs minus her rear end. Therefore, after being stung, the first thing to do is to remove the stinger. I did that easily with my fingernails.

It seems that none of the old bee-sting treatments really work, other than by the placebo effect -- not damp pastes of tobacco, salt, baking soda, papain, toothpaste, clay, garlic, urine, onions, aspirin or even copper coins. Ice might help, but not much. Basically, for most people, if you get stung there's not much you can do about it except cool it off.

from the April 20, 2003 Newsletter issued from the woods a few miles south of Natchez, Mississippi; elevation ~200ft (~60m), ~N31.42°, ~W91.41°;, USA

HONEYBEES SWARMING

Monday morning as the sun shone with brilliance and the temperature stood at about 75° (24°C), I was transplanting pepper plants in the garden when I became aware of a persistent buzzing. I'd heard that sound before, so immediately I set off looking for swarming honeybees.

I found them busy around a hole about 30 feet up (9 m) in an old Pecan tree. Years ago someone had cut a large branch there, the center of the cut had rotted out, and probably the rot had extended into the trunk forming a cavity perfect for a beehive.

For about five minutes I watched as a diffuse, smudgy cloud of swirling bees hung around the hole. Then the smudge expanded ameba-like toward the top of an American Elm about 40 feet away, and finally it separated from its Pecan-hole home. Now it began coalescing into a churning, compact sphere at the elm's very top, where the whole dark blur paused for several minutes, as if snagged there. Though the morning was breezeless, the elm's topmost leaves fluttered in drafts made by the bees' wings.

Now during about 20 minutes as the bee cloud settled among the elm's topmost branches, a grainy black and yellow stain began forming on a particular branch about two inches thick (5 cm) and some 10 feet below the elm's top leaves. The stain consisted of thousands of bee bodies massing together. In half an hour the bees hung on the branch like a three-foot-long, yellow-and-black beard. The swarm had moved only about 40 feet, but I'd witnessed the birth of a new honeybee colony, and it had been an amazing thing to see.

Much work had preceded this birth. When a honeybee colony becomes too crowded with adult bees, worker bees select a dozen or so tiny larvae already in the hive. Normally these larvae would develop into worker bees, but now they are fed generous amounts of "royal jelly," a substance produced by certain brood-food glands in the heads of worker bees. The cells in which the chosen larvae are developing are enlarged, for these larvae will develop into queens.

Shortly before these new queens emerge, the hive's original mother queen departs from the hive with about half of her worker bees (usually from 15,000 to 25,000), and this is what I witnessed Monday. After a brief flight the queen alights, usually on a branch of a tree but sometimes on a roof, a parked car, or just about anything. All the bees settle into a tight cluster around the queen while several scout bees go looking for a new place in which to live. When the scouts find a new location, the swarm goes there and begins a new colony.

from the July 6, 2003 Newsletter issued from the woods just south of Natchez, Mississippi, USA

HONEYBEES COLLECTING GRASS POLLEN

The grass in which my evening cottontail hops is Carpetgrass, genus AXONOPUS. It's a tough species with thick, wiry stolens, a species mostly restricted to the Deep South, and which in our area often takes over marginal land that's occasionally bush-hogged. Carpetgrass blades look like any lawn grass, but its flowering shoots, or inflorescences, grow nearly knee high and consist of two slender flower spikes arranged in a shallow V atop a slender stem. If you're trying to keep your lawn "neat" and you have Carpetgrass, these flowering spikes will drive you nuts, for they emerge soon after any mowing, and are pretty conspicuous.

Certain bees love this grass. Nowadays you see them collecting pollen from the purplish-black anthers dangling from the inflorescence's flowers on slender white filaments. The bee lands at the bottom of the inflorescence's V, takes two to five seconds to climb up a spike, then flies to the next grass to repeat the operation. This is done again and again. During these climbs pollen catches in hairs on the bees' legs. The bees then pack the pollen into little pollen baskets on their legs.

If bees can collect nectar, why should they bother with dusty, messy pollen? The main answer is that nectar, just like Coke and Pepsi, contains plenty of calories, but not enough protein, vitamins and other nutrients to keep a body alive. Using special glands in their heads, bees convert pollen into a highly nutritional "brood food" for their young.

In fact, the sale of bee-collected pollen has become a real industry among humans, too. The hype at one Web site selling "bee pollen" tells us that bee pollen contains "All 22 elements of the human system. All essential amino acids and is a complete protein. Vitamins A, B Complex series C, D, E, K and Rutin. 28 Minerals, Trace Mineral needed for good health. Enzymes and Co-Enzymes necessary for good digestion. No cholesterol. Only 90 calories per ounce... "

Happily, bees are not killed in order to rob them of their pollen bags. When bees from which pollen is to be collected enter their hives they crawl through a series of 1/4-inch wiring. During this maneuver pollen is scrapped harmlessly from their legs, then drops into a tray for collection.

issued on September 3, 2019 from near the forest just west of Tepakán; elev. ~9m (~30 ft), N~20.053°, W~89.052°; central Yucatán state, MÉXICO

COMB WITHOUT A HIVE

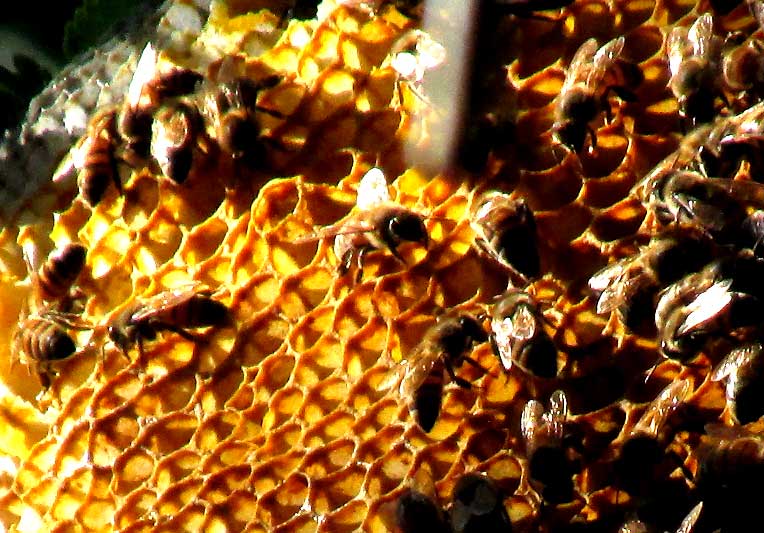

In the secondary forest near the hut the honeybee comb seen below turns up, about 15ft off the ground (4.5m):

I've heard that sometimes swarming honeybees settle on a tree limb, have a hard time finding a proper hollow tree in which to establish a new hive, and begin building a comb on the limb. However, my impression is that this is larger than such a temporary comb should be. Below you can see how thick the comb is, photographed from beneath the comb:

A close-up of the bees is shown below:

A month after the above pictures were taken, the comb remains. It hasn't been enlarged, but rather now has holes all through it and the bee population seems to be much diminished, and less active than before. My impression is that the swarm has given up and is dying.