Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the May 27, 2012 Newsletter issued from the woods of the Loess Hill Region a few miles east of Natchez, Mississippi, USA

EASTERN CHIPMUNKS

What astonishes me about this area's Eastern Chipmunks, TAMIAS STRIATUS, is that there's so many of them. Of course Karen's cat brings in one every few days, plus there's a Jack Russell terrier who obsessively hunts them in the adjacent woods day after day, keeping the crows supplied with chipmunk carrion dropped along the driveway. It seems that we'd have run out of chipmunks in this area long ago, yet the bodies keep appearing, and nowadays there's even a perky one who occasionally ventures into the mid-afternoon sunlight, sneaks past snoozing dogs and cats, and climbs the shadowy side of the Black Oak just outside my window, as shown below.

I read that Eastern Chipmunks over most of their range produce two litters a year of 4-5 babies, so that birthrate certainly explains a lot, but still it hardly seems enough to keep supplying all the carcasses that appear here.

If you study the facial profile of the chipmunk in the picture it's easy enough to believe that chipmunks are rodents, which they are, like squirrels. In fact, chipmunks are regarded as small squirrels, residing in the Squirrel Family, the Sciuridae, along with tree squirrels, ground squirrels, woodchucks, flying squirrels and prairie dogs. They're all rodents -- members of the order Rodentia, class Mammalia.

With those "racing stripes" along their sides, in Eastern North America chipmunks can't be confused with anything else. However, out West there exist several similarly striped chipmunk and antelope-squirrel species, as well as the Golden-mantled Squirrel, all with stripes and looking pretty much like Eastern Chipmunks.

Literature usually says that Eastern Chipmunks live in rocky areas, but around here we have no rocks, since the entire landscape is mantled with end-of-Ice-Age-deposited dust called loess. However, on steep slopes often the loess erodes away beneath trees leaving root mazes behind which chipmunks love to dig their burrows.

Eastern Chipmunks eat bulbs, seeds, fruits, nuts, green plants, mushrooms, insects, worms, and bird eggs, often transporting their food in cheek pouches. The species occurs throughout forested eastern North America except for most of the US Deep South. I'm guessing that it's missing from the Deep South because the Coastal Plain there is geologically so young that rocks and boulders haven't had time to harden from sediment, or lithify, and chipmunks genuinely need those rocks and boulders, or else our tree-root tangles on steeply eroded loess slopes. Here in southwestern Mississippi we're right at the Eastern Chipmunk's most southwestern point of distribution.

from the May 27, 2012 Newsletter issued from the woods of the Loess Hill Region a few miles east of Natchez, Mississippi, USA

CHIPMUNK CHEEK POUCHES

Titmice aren't the only ones outside my window carrying more food than they seem capable of swallowing. A chipmunk regularly comes, stuffing his cheek pouches with acorns, as you can see below:

Those pouches are used not only to transport food but also for carrying nesting material, and when burrows are dug the excavated soil is carried away in the pouches so there'll be less chance of predators noticing the digging.

from the December 15, 2002 Newsletter issued from the woods of the Loess Hill Region a few miles south of Natchez, Mississippi; elevation ~200ft (~60m), ~N31.42°, ~W91.41°; USA

CHIPMUNKS BUSH DIGGING

The one-lane gravel road into the bayou between here and the gardens cuts through loess and passes between near-vertical walls encrusted with mosses, liverworts and ferns. Trees with Spanish Moss overhang the little trail and each day I feel lucky to "go to work" through such an idyllic tunnel.

Many Eastern Chipmunks, TAMIAS STRIATUS, have their own tunnels in the loess banks along the road and I hardly ever fail to see one or more. Now that acorns are falling they are especially busy. When collecting food for their storage burrows they work obsessively, continually running back and forth between the food source and the burrow. Over three days someone watched a chipmunk store a bushel of chestnuts, hickory nuts and corn kernels.

Here and there along the loess banks chipmunks have created nearly straight, horizontal runways ten feet (3 m) long and longer. Sometimes you'll hear a sharp whistle of someone you've sneaked up on and then you'll see them high-tailing down these runways toward their burrows, zipping beneath fern fronds and tree roots at amazing speeds. Most runways are built just beneath the overhanging sod formed by the forest floor above, so most runways remain dry. They are like tunnels open to view on one side. Sometimes I imagine being a chipmunk hustling down a runway beneath roots, overarching fern fronds, the wall below richly green with moss and liverwort... as on an enchanted Hobbit trail.

Lately I've been seeing freshly dug dirt scattered over large areas of moss, liverworts and ferns, so apparently some chipmunks are "digging in for the winter." Much of the digging takes place beneath tree roots at the top of the banks, and I fear that this causes many trees, over time, to lean inexorably over the road. During heavy rains often one or more of these trees fall, and this doesn't endear chipmunks to the plantation manager.

In fact, around the manager's house a general war with the chipmunks has been going on for years. Chipmunks are accused of gnawing insulation off the vehicles' engine wires and of devouring precious flower tubers and rhizomes. I have kept quiet about the fact that during the winter they enter my coldframe and eat seeds I've planted. Also, this summer they invaded the garden area I'd protected from burrowing Pine Voles by sinking corrugated tin sheets all around, and eaten nearly my entire crop of Jerusalem Artichoke tubers!

This summer a chipmunk lived beneath my trailer. Often as I prepared breakfast he'd run out, see me, come to a screeching stop, look at me full in the face, then either streak back beneath the trailer or shoot past my legs into the woodpile. I knew it was always the same chipmunk because half of his tail had been chewed off.

I haven't seen this chipmunk for a while and I suspect that he has become someone's meal. I'll never forget the look on his face when one day he came from beneath the trailer with his cheek pouches absolutely gorged with something, then saw me and put on his brakes so fast that his rear end raised from the ground.

from the January 18, 2004 Newsletter issued from the woods of the Loess Hill Region a few miles south of Natchez, Mississippi; elevation ~200ft (~60m), ~N31.42°, ~W91.41°; USA

LOWER JAWBONE OF A CHIPMUNK

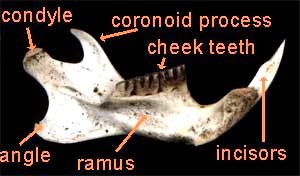

Thursday while renewing the pinestraw mulch around my azaleas I discovered two perfect little jawbones in the old mulch. Judging from their sizes, only 1¼-inch long (33 mm), I figured they belonged to a woodrat, of which there are plenty around here. However, when I "keyed them out," they proved to be chipmunk jaws.

The identification was made possible by a 40-page, plastic-comb-bound pamphlet entitled "A Key-Guide to Mammal Skulls and Lower Jaws.".

Fortunately the pamphlet is illustrated, because to identify the jawbones I needed to check the features of such bone parts as the ramus, coronoid process, condyle and angle, and I'd never heard of those things. It turns out that a chipmunk's "tip of coronoid process lies about 4-5 mm in front of angle," and that the "lower edge of ramus, just in front of angle, curves or turns inward." I scanned the jawbone and you can confirm these details yourself by viewing the labeled image below: