Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the September 1, 2013 Newsletter issued from the Frio Canyon Nature Education Center in the valley of the Dry Frio River in northern Uvalde County, southwestern Texas, on the southern border of the Edwards Plateau; elevation ~1750m (~5750 ft); N29.62°, W99.86°; USA

STRANDED BASS

The Dry Frio River is the driest I've seen it during my year here, in most places its waters shrunk to occasional shallow pools, as shown below.

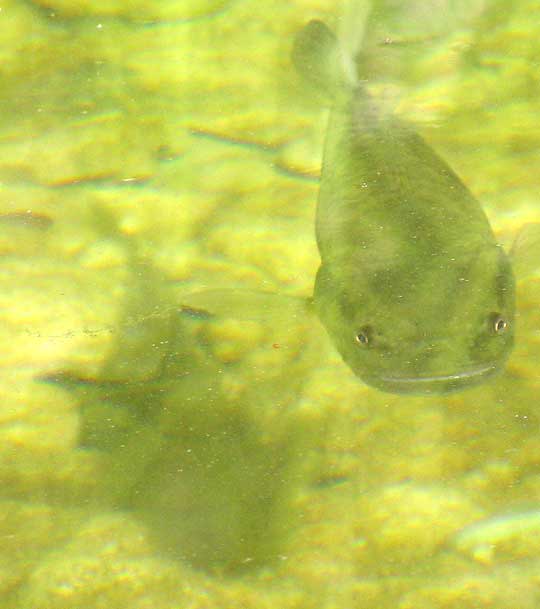

The pools are not stagnant because water drains from the upstream side to the downstream, between pools flowing beneath the dry streambed's cobblestones. Maybe that's what keeps the fish in the pools from dying, for most pools contain a good number of stranded fish, which are easy to see. In most pools the most common fish species is the one shown at the top of this page.

Below, you can see the same foot-long fish turned and looking at me, showing a wide body and widely set eyes above an ample mouth:

I don't know my fish too well but I have fair confidence that this is a Largemouth Bass, MICROPTERUS SALMOIDES. I'm confident not only because it looks like a Largemouth, but also because the species is known to be common not only throughout Texas but also in the Dry Frio River. In fact, certain streams in our area have been stocked with Largemouths. An article at Statesman.com says, "In Texas, bass fishing is a multi-billion-dollar industry, and it's supported by more than 2 million freshwater anglers and an official state apparatus that spends millions of dollars a year to breed larger, heavier fish and release them into lakes and rivers."

That article also makes the interesting point that the millions of baby bass stocked into Texas waterways each year do virtually nothing to increase any angler's chances of catching a fish. They are put there to modify the gene pool of the existing natural population.

At the root of this genetic manipulation is the fact that two subspecies of Largemouth Bass are recognized: the typical one, and one known as the Florida Largemouth Bass. The Florida version grows larger. Since fishermen prefer larger fish, the Florida subspecies is being stocked in Texas.

Because the Florida subspecies enjoys a whole range of adaptations to the Florida environment, not just growing larger, the idea of flooding Texas populations with Florida genetic material gives me the creeps.

Despite the mess humans are making of its genome, the Largemouth Bass is an impressive species, one able to eat just about any living thing it can get into its mouth, and one that thrives in many kinds of water, from gushing mountain streams to muddy ponds with low oxygen levels.

In the pool in the picture our foot-long fish swam back and forth again and again, surrounded by fingerlings of the same species, and I wondered how they could all remain so active with so little apparent food available there. Maybe the big one eats the little ones, but what do the little ones eat? Also I wondered how long all of them will last if we don't get rain pretty soon.

from the September 15, 2013 Newsletter issued from the Frio Canyon Nature Education Center in the valley of the Dry Frio River in northern Uvalde County, southwestern Texas, on the southern border of the Edwards Plateau; elevation ~1750m (~5750 ft); N29.62°, W99.86°; USA

A MEAL

While taking pictures of Bluegills, suddenly there was a loud, slapping splash of water across the pool at the very edge, and a V-shaped wave slicing away from the splash. A Largemouth Bass had caught something to eat and had it in his mouth. I got his picture as he passed by, not a sharp one because of the fast action, low light and consequent slow shutter speed, but below you can see part of what he caught sticking from his mouth:

That's clearly a fish's tail poking from his mouth, probably that of a Bluegill. The bass swam back and forth in the pool as he manipulated the fish into a different position. Below, you can see the Bluegill bent so severely that surely his back is broken, the lobe at the top apparently a gill:

Ten minutes later the Bluegill had been turned into yet another configuration, as seen below:

Twenty minutes later the bass still hadn't swallowed his meal and now was swimming back and forth with the prey's head sticking from his mouth, with clumps of bladderwort collecting against his lips, as seen below:

At this point I wandered away, but returned about 45 minutes later, and at that time the bass must have swallowed his meal. He was hovering over one spot in the pool, breathing fast through his wide-open gills the way fish do when they're excited or upset.

So now we know that the larger fish in these isolated, drying-up pools survive by eating the small fish, but it's still hard for me to imagine how all those smaller fish themselves have enough to eat. There just aren't that many dragonflies allowing themselves to be snatched up.