Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the February 28, 2016 Newsletter issued from Hacienda Chichen Resort beside Chichén Itzá Ruins; limestone bedrock; elevation ~39m (~128ft), N20.675°, W88.569°; central Yucatán state, MÉXICO

VIRGINIA CREEPER IN THE YUCATAN

Last weekend when I escorted volunteer insect identifier Bea of Ontario to Mérida for her departure, my friends Eric and Mary were kind enough to invite us for an overnight visit. While there we had time to explore the backyard garden, which featured species you'd never see up north as well as, climbing up the wall, a very familiar looking woody vine. The vine's purple, silvery-bloom-covered fruits and deciduous leaves with five tooth-margined leaflets is shown below:

Eastern North America's woods are filled with something looking exactly or almost exactly like this, the Virginia Creeper, Parthenocissus quinquefolia, of the Grape Family, the Vitaceae. You can compare Eric's vine with our picture of Virginia Creeper in Mississippi at www.backyardnature.net/n/w/va-creep.htm.

The leaves on Eric's vines struck me as somewhat smaller than those on Virginia Creepers up north and less "veiny." Virginia Creepers are widely distributed and somewhat flexible in habitat requirements, even occurring in Mexico, but certainly the Yucatan Peninsula is too arid for it. When I told Eric it looked like Virginia Creeper to me he said that he'd bought it labeled as Cissus silvestris, Cissus being a mostly tropical genus closely related to the Virginia Creeper.

Back at the Hacienda on the Internet I quickly determined that Cissus silvestris bore leaves consisting of a single blade, not five leaflets like Eric's vine, so the vine had simply been labeled wrong. However, I also saw that the Grape Family embraces several genera producing tendril-bearing woody vines that sometimes are planted in gardens and vineyards, and numerous species, so to be sure about the identity of Eric's vine I had to look closely and "do the botany."

First of all, a typical compound leaf on Eric's vine is shown below:

In that picture the yellow threads in the background are parasitic dodder stems bearing no flowers or fruits but sprawling over and stealing water and nutrients from a Papaya tree as well as the vine, possibly the same dodder species we looked at a couple of weeks ago, at www.backyardnature.net/mexnat/dodder.htm.

Notice the leaf's red petiole and how the redness extends up the leaflets' midribs. Up north, Virginia Creeper is famous for its brilliantly red, late-summer and fall foliage.

Despite Eric's wall-vine bearing mature fruit, some of his potted plants displayed flower buds and flowers, shown below:

In that picture the spherical items are flower buds, and the yellow things are flowers. You can see how the buds' surfaces display five pie-slice-shaped divisions -- these are future sepals all together to form the future calyx -- separated by shallow grooves. This "cap" covers the flower's sexual organs. In the Grape Family usually the sepals only partly separate from one another before the whole cap falls off, exposing the sexual organs.

That's happened to the two yellowish flowers, which consist of nothing but the female ovary, its style and stigma. There's no trace of male stamens in the flowers in the picture. The genus Parthenocissus takes its name, however, from the classical Greek parthenos, meaning "virgin", and kissos, Latinized to cissus, meaning "ivy," translating to "virgin ivy," because Parthenocissus fruits can set seeds without pollination. For Parthenocissus flowers, having no stamens is no big deal.

In the end, Eric's vine turned out to really be Virginia Creeper, PARTHENOCISSUS QUINQUEFOLIA. The variety engelmannii produces smaller foliage, so maybe we have that.

One reason for Eric planting Virginia Creeper is that he wants to use it as insulation for his home against the Yucatan's scorching sunlight. He took me a few blocks from his house to look at one homeowner's use of the vine as a dark curtain overhanging windows, shown below:

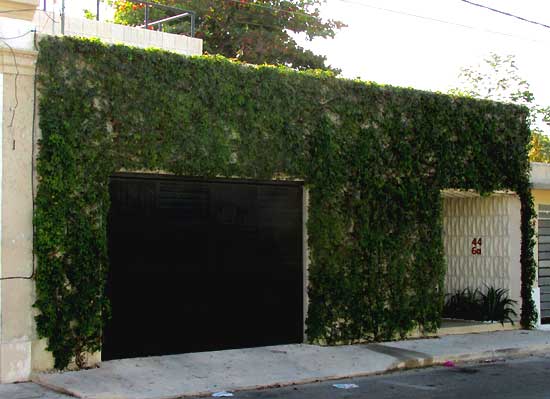

On another street, a building's entire front wall was covered with it, shown below:

Eric believes that there's enormous potential in this area for cooling buildings and cutting down on the glare by covering them with sunlight-absorbing Virginia Creeper, and I think he's exactly right.