Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the June 28, 2015 Newsletter issued from Río Lagartos, on the Yucatan Peninsula's northern coast (~N21.60°, ~W88.16°), Yucatán state, MÉXICO

TROPICAL MISTLETOE

At the mangrove's edge the branches of many Buttonwood trees bear tangled clumps of wiry stems with small, fleshy leaves, as shown below:

Below, you can better see the stems' vininess, somewhat succulent leaves and small flowers clusters:

The leaves look like those of the North's mistletoe species, but who's ever heard of a viny mistletoe? In the above picture, notice the blunt, root-like appendages emerging from here and there on the stem. Elsewhere the vine's woody stems wound around the tree's limbs "rooting" these appendages on the limbs' surfaces in the manner of parasitic dodder, as seen below:

Could this really be some kind of viny mistletoe, then? The flower clusters were examined to see if they looked like mistletoe flowers we've seen before, and they didn't, as shown below:

A closer look at two flowers appears below:

There, on the flower at the right, a green, cup-like calyx with no lobes or sepals can be seen inside which a tubular, yellowish-green corolla arises bearing stamens with whitish, curved anthers surrounding a cauliflower-like stigma. The corolla bears six petals instead of the five more often found in other such flowers, plus the stamens arise opposite the corolla lobes, not between them the normal way. This latter feature goes a long way toward helping decide what plant family we have here.

The flowers looked to me most like those of the Grape Family, one of the few families whose stamens arise opposite corolla lobes, but Grape Family flowers have corolla tubes with four or five lobes, not six. However, the Mistletoe Family, the Loranthaceae, usually has six-lobed corollas and its stamens also arise opposite the lobes, so here we did have some kind of viny mistletoe, something completely new to me. You might enjoy reviewing what typical mistletoe flowers look like up north -- these in Texas -- at www.backyardnature.net/n/14/140223ms.jpg.

Sometimes species in the Mistletoe Family bear unisexual flowers, though these flowers seem to have both functional male and female parts. More mature flowers on this same plant had discarded their corollas, revealing healthy-looking but curiously kinked styles projecting from what seemed like ovaries destined to become fruits, as shown below:

Still, it was worth comparing these flowers with those on other viney mistletoes living among Buttonwood branches along the mangrove's edge. No obviously unisexual flowers were found, but some did show up displaying certain curious features, shown below:

Though I find no mention in the literature about it, those little white things on the flower's corolla lobes look like glands at the tips of anthers temporarily stuck to recently opened corolla lobes. Maybe the idea is for ants to come along, tug at the tasty gland, and help the anther unstick? Other flowers on other plants sometimes showed this condition, too. Who knows?

While "doing the botany" and still uncertain what plant family we had here, I'd made a cross-section of an ovary, finding it containing a single cell, which is OK if we have a mistletoe, shown below:

So, this is STRUTHANTHUS CASSYTHOIDES, a true mistletoe of the Mistletoe Family, but a genus I hadn't recognized before. The species occurs from the Yucatan Peninsula south to Costa Rica. In the Yucatan it seems to be fairly common. Here along the arid northern coast I've noticed it only on Buttonwood trees, though an online paper from Nicaragua describes it as a serious parasite on citrus trees there, and numerous other tree species. Another Struthanthus occurs here, but its flower clusters are longer and more open.

It's worth remembering that the northern, Christmas-decoration-type mistletoe, in the genus Phoradendron, recently have been banished from the Mistletoe Family and relegated first to the Viscaceae, then to the Santalaceae. What we have here, then, having been retained in what's traditionally thought of as the Mistletoe Family, is a real, real mistletoe, though one without a decent English name. It might as well be called Tropical Mistletoe, like several other species, since it's not found up North.

It's also good to remember that mistletoes are only partially parasitic, though they are firmly rooted in their host trees. They do have green leaves, which photosynthesize the carbohydrates that are their real food, but they rob their host tree of sap.

Entry from notes taken during a camping trip, on April 2, 2019, to Seibal Archaeological Park about 15kms east of Sayaxché, Petén department; tropical rainforest, elevation ~220m (~720 ft), ~N16.492°, W90.209° GUATEMALA

A TREE COVERED WITH MISTLETOE

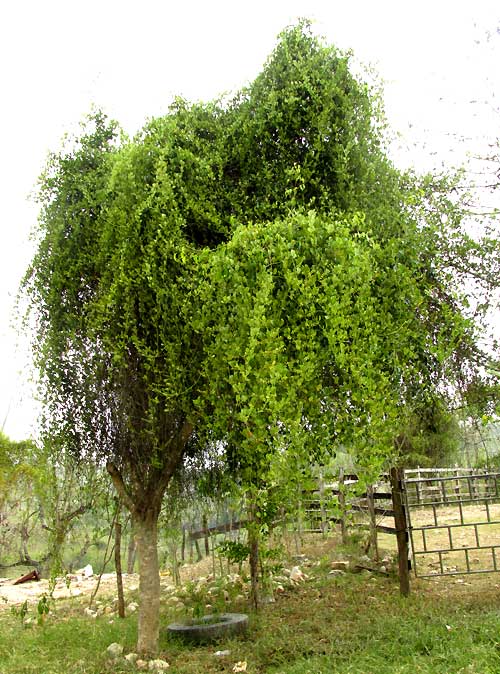

Hiking out of the park, on the little gravel road about 5kms north of Paraiso, beside the road next to a ranch a Madred de Cacao tree, Gliricidia sepium of the Bean Family, mostly leafless because of the dry season, was almost completely covered with a semiparasitic vine, as shown below:

Up close I had one of those similar-but-different experiences, brought about by what's shown below:

But the flowers seen close up seemed to be just like something I'd seen, shown below:

Eventually I realized that in fact I've seen this species before, at the edge of a mangrove swamp in northern coastal Yucatan, but that plant had been much, much less robust that this Guatemalan population. Especially the Yucatan plant's flowers had been much less numerous in relatively small clusters. Maybe it was because of the northern Yucatan's aridness. Whatever the case, here was a different appearance of the tropical mistletoe Struthanthus cassythoides.