Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the October 26, 2018 Newsletter with notes from a camping trip into northern Guatemala's Petén department; tropical rainforest, elevation ~220m (~720 ft), ~N16.492°, W90.209°

PANAMA RUBBER TREE

During my recent camping trip south to El Rosario National Park, on Sayaxaché's east side in northern Guatemala's Petén department, as I explored the campground's perimeter on October 1, I came upon the tree trunk and sign shown below:

The sign says that it's the Rubber Tree, CASTILLA ELASTICA, a member of the Fig Family, the Moraceae, and that it's used for making xylophone drumsticks and rubber balls.

Historically and botanically, this is an important tree, one not occurring in the Yucatan's semiarid forests, and I was glad to meet it. The tall tree -- they can grow up to 100 feet tall, exceptionally to 200 ft (30-60m) -- didn't appear to be flowering or fruiting, but at least the camera's telephoto lens could show us its leaves glowing in sunlight far above, shown below:

In the forest, these fair-sized leaves are easily recognizable because of their oblong shape becoming a little larger toward their apexes, plus the rounded lobes at the blades' bases, and the ±straight, close-together secondary veins creating a "herringbone pattern." And if we could reach up and make a little tear along a leaf's margin, most likely white latex would ooze from the severed veins, as with most members of the Fig Family.

This isn't THE Rubber Tree, Hevea brasiliensis, from which early car tires were made, and for that reason in English we usually call our Guatemalan species the Panama Rubber Tree. Hevea brasiliensis, belonging to a different family, the Euphorbia Family, doesn't occur in our part of the American tropics, but our Panama Rubber Tree is broadly distributed in rainy tropical lowland areas from southern Mexico south through Central America into northern South America. Our tree has been used to make rubber, too, though the rubber is considered inferior to that derived from Hevea brasiliensis.

Though our tree's inferior rubber has seen days when it was exploited commercially, its greatest claim to fame may be that back when Mesoamerican indigenous people were playing their famous life-or-death ballgames, the balls they used were made from the milky-white latex of Panama Rubber trees. Interestingly, the tree's milky latex was coagulated into usable rubber by mixing it with juice from the commonly occuring morning-glory vine we call Moonflower, shown at www.backyardnature.net/mexnat/ipomoea.htm

from the April 20, 2019 Newsletter with notes from a camping trip into northern Guatemala's Petén department

PANAMA RUBBER TREE FLOWERING

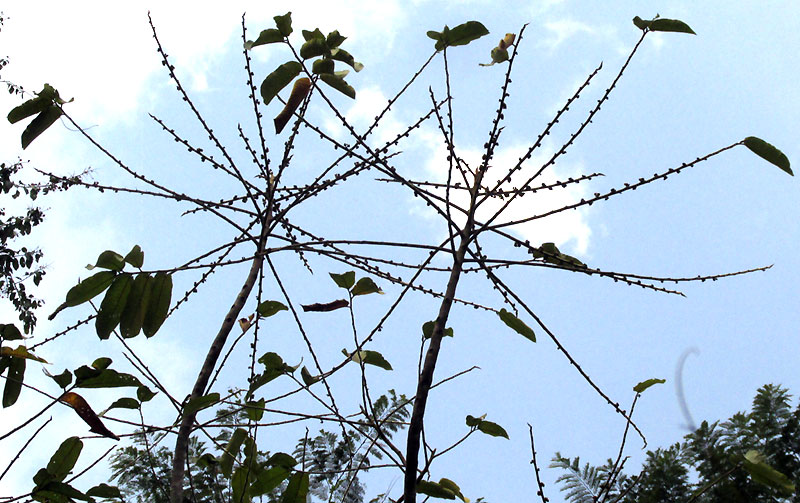

Earlier this month, on April 1 -- now toward the end of the dry season -- along woodland trails through the extensive Maya ruins in Seibal Archaeological Park about 15kms east of Sayaxché, the Panama Rubber Trees had dropped most of their leaves because of the dry season, and they were flowering. And flowering, they presented a curious spectacle, as shown below:

At first I could hardly believe that Panama Rubber Trees could look like this, but zooming in on some leaves with the camera's little telephoto lens revealed that they were, as you can confirm below:

While I was at it, I got a close look at the naked, flowering part of the stems and saw something interesting, shown below:

It looks like flowers have fallen off most of the stems' flowering spots, but here and there flowering structures remain, looking like small fruits. Being members of the Fig Family, the Moraceae, Rubber Trees produce unisexual flowers, and in this genus an individual tree may bear both male and female flowers (the tree is monoecious) or only flowers of a single sex (dioecious). These limbs were about 12m high (40ft), and at such distance I just couldn't be sure what I was seeing, in terms of male/female flowers.

However, farther along a trail the ground was heavily littered with strange-looking items about 25mm across (1 inch), one of which is shown below:

That's a Panama Rubber Tree flowering structure bearing male flowers.The white, grainy items are pollen producing anthers, so this structure is a kind of curved platform shaped somewhat like a distorted golfball tee, known as a receptacle, with overlapping, scale-like bracts on its bottom, and many closely crammed together male flowers on top. All the flowering branches were too high to see whether there were receptacles bearing female flowers. It makes sense that the trees would drop their male flowers once their pollen was shed, while the female structures would remain, to develop into fruits.

I was delighted with this male-flower-bearing receptacle because it fit so nicely with what I know of the Fig Family. To see what I mean, you can compare the above male fruiting structure with the female flowering structure of a Fig Family member, the Snakewort, commonly growing around the hut I live in, in the Yucatan, at www.backyardnature.net/n/16/160703dt.jpg

The structures are very similar, yet one plant is our big tree, and the Snakeworts beside the hut are the ankle-high herbs shown at www.backyardnature.net/yucatan/dorsteni.htm

And a fig "fruit," then, is nothing but a flowering receptacle like those of the Rubber Tree and the Snakewort, but completely curved in on itself, to form a sphere, with the flowers on the sphere's interior wall. When you eat a store-bought fig, you're eating a receptacle and the grainy flowers and fruits inside the receptacle. A typical fig, of the tree Ficus obtusifolia, is shown in cross section showing all this at www.backyardnature.net/mexnat/ficus-o.htm