Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

Entry from field notes dated May 7, 2023, atop hill forested with pines and oaks about 1km east of Curva de la Doctorcilla, on unnamed road connecting Hwy120 and El Doctor; limestone bedrock; elevation ±2650m (8700 ft); Eastern Sierra Madre mountains of east-central Querétaro state, MÉXICO, (N20.88°, W99.62°)

ENTODON BEYRICHII MOSS

Atop a hill forested with oaks and pines, the latter dead or dying from pine beetles, at eye level on a dying pine's bark the above moss was prospering. Because mosses are small, often critical identification can't be seen without magnification; for me, most mosses must pass without knowing who they are. However, the above was so eye-catching that it seemed worth a try.

Notable features include its bright, even shiny, yellow-green color. At the picture's top right, notice that stems emerging from the main colony creep along the tree's bark, while issuing upward-tending branches. Moss stems can grow singly, form compact, often roundish tufts, or make carpets over a foot across or, like ours, form irregular-shaped mats. Noting just these features of growth form disqualifies most of the world's 12,000 or so moss species, of which nearly a thousand are documented from Mexico.

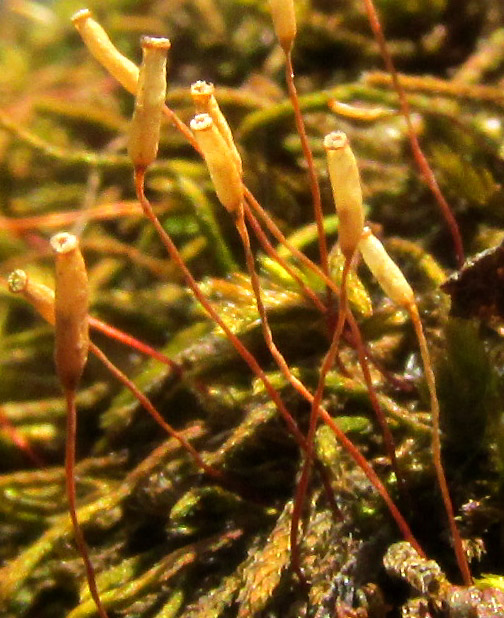

As flowers and fruits usually are needed for identifying flowering plants, spore-producing capsules like those above usually are needed for moss identification. Glancing at the drawing at the right, it can be seen that our capsules already have discarded their caplike calyptras and the opercula and annuluses below the calyptras. The urns atop their stalks remain, however, and the ring-like peristomes atop the urns still bear white teeth. The urns, with a certain longish, slender form, are darker at their bottom halves, maybe indicating spores remaining in the urns. Peristomes at the urns' openings manage the urns release of spores, so they don't all pour out at once. Our mosses' stalks also display a certain tallish height, and are pale rusty-red. The capsules of many mosses are tilted, from slightly to a great deal, even beyond 90°, depending on the species, so our capsules standing erect also is an important field mark.

The creeping stems bear scoop-shaped leaves gradually tapering to sharp tips. The leaves are arranged in several rows around the stems, not opposite one another as with many species. Leaf margins of many species are conspicuously toothed, at least toward their tips, but in the picture, if teeth are present, they're too tiny to see. The leaves' shiny yellow-greenness is even more apparent here.

When reviewing Internet images of Mexican mosses, at first glance most of them are confoundingly similar. However, keeping the above features in mind, gradually the mind learns to discriminate, and in such a way I was led to the genus Entodon. Entodon comprises about 70 species worldwide, and is best represented in South America's Andes, and eastern Asia. In eastern North America where I grew up, Entodon seductrix was a common species on various substrates in hardwood forests, and at first I thought we had that.

However, that species is basically an eastern North American species, only spottily observed elsewhere, including in Mexico. Entodon seductrix has been identified growing along a street in a suburb of Toluca, Mexico state, at an elevation of about 2600m, close to the same as here so there's no reason for our moss not to be that one. On the other hand, there's a closely related, very similar species specializing in the central Mexican uplands, with us at the heart of its main distribution, and commonly observed in upland Mexico, and that's ENTODON BEYRICHII, with no common English name.

Entodon beyrichii enters the US along the Mexican border, where it's described as inhabiting logs, rocks and other exposed, dry habitats. The Flora of North America distinguishes Entodon beyrichii from Entodon seductrix by noting that the mostly Mexican Entodon beyrichii bears microscopic bumps called pappillae at the bases of the tiny teeth atop the capsule's urn, while the teeth of Entodon seductrix are smooth. Without a microscope, I can't be certain which of the two species we have, though past indentifications indicate that by far the greatest probability is that our moss is Entodon beyrichii.

As stated in the 2020 study by Enrique Hernández-Rodríguez and Claudio Delgadillo-Moya entitled "The ethnobotany of bryophytes in Mexico," there's little information about human uses of mosses in Mexico. However, they do report people collecting them at Christmas, to decorate Nativity scenes. In upland Chiapas I've seen where each Christmas large moss carpets would be scalped away, leaving slopes vulnerable to erosion.

Our patch of moss on a pine trunk in a forest whose canopy was opening up because of beetle-killed pines can be seen as something living moving into an area where much death is taking place. Just seeing this vigorous splash of greenness busily releasing spores into the air, encouraging new greenness to appear elsewhere, made me feel better.