Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

Entry dated February 7, 2024, issued from near Tequisquiapan; elevation about 1,900m, (6200 ft), ~N20.57°, ~W99.89°; Querétaro state, MÉXICO

AGERATINA BREVIPES

The above chest-high woody shrub in full flower was a surprise. We're deep into the usual dry season, after two years of weather the North American Drought Monitor characterizes as a D3 Extreme Drought, and simply no other wild-growing native plant in this area is in such a gloriously unreserved state of blossoming. Even the tree I've assumed to be the most drought-hardy woody species in this region, Sweet Acacia, currently bears only a meager few blossoms, those still present fading and falling off, offering hardly any of their usual fragrance, and leaving behind fewer than normal developing legumes.

The Flora del Bajío describes the above complex inflorescence structure as consisting of compound corymbs arranged in terminal racemes. Corymbs are flat-topped racemes with long pedicels reaching the same level, and racemes are flower clusters with flowers on short stalks, or pedicels, attaching to the central axis, or rachis.

The above flowering head stands next to a ruler with marks in millimeters, so the green involucre enveloping the florets is 4-5 mm high, which is fairly short for such robust heads. The involucre's scale-like phyllaries are arranged in two series of somewhat equal length.

A dissected head, or capitulum, reveals no scale-like paleae separating the individual one-seeded, cypsela-type fruits.

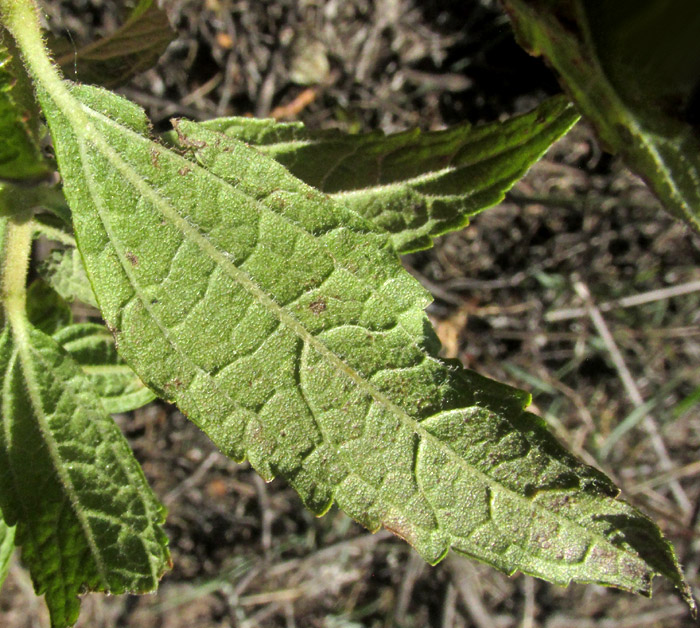

Until now, features seen above are similar to numerous other white-flowered members of the Aster or Composite Family which produce no petal-like ray florets at the flowering heads' margins. Seeing such flowering heads on woody stems suggests the genus Ageratina, whose many species often are called snakeroots. However, leaves of all but a few Ageratina species are much broader than the above, and are attached to considerably longer petioles. The blades of only a few Ageratina species develop such strong secondary veins arising from the blade base, and paralleling the blades' margins. Our bush's leaves are unusually wrinkly, and their top surfaces are somewhat resinous, but not as sticky as in some Ageratina species. Finally, note how the blades' teeth cluster on the upper half, and the blades themselves are widest at their middles. This species is best known by its leaves.

Blade undersurfaces were sparsely hairy and exhibited prounounced, strongly reticulating veins.

Stems and petioles were strongly hairy, with only a few scattered hairs tipped with glands.

At the right, the bush's woody trunk rises among thorny stems of Desert Hackberries.

All the above features, especially those of the leaves, lead us to AGERATINA BREVIPES, with no English name other than the general name snakeroot used for many species. It's endemic just to Mexico, found in grassy and scrubby uplands from Durango state in the northwest, through the central uplands, south to Oaxaca state.

Probably our bush existed only because it grew entangled with spiny mesquites, mimosas and Desert Hackberries, where roving livestock couldn't reach it. The presence of such a lushly flowering bush in a thicket at the edge of a large, parched, profoundly overgrazed and eroded abandoned field was more than surprising: It was a mysterious presence, and I wondered how it managed so well.

Here's a wild guess at what's behind the mystery: All the main branches of the Smooth Mesquite next to it had been sawed off by firewood gatherers, so could this bush somehow be benefiting from the mesquite's deep roots, now of much less use to the amputated companion? Slowly it's being realized that in healthy biological communities different species help one another by way of sharing fungal mycorrhizal networks. Among trees, the process is referred to as arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Wikipedia has an excellent Arbuscular Mycorrhiza page.

In the 2018 study by Luisa Lanfranco and others entitled "Partner communication and role of nutrients in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis," it's stated that "Nutrient exchange is the key feature of AM symbiosis," AM being arbuscular mycorrhiza. Moreover, the work by Daniel Wipf and others in the 2019 study entitled "Trading on the arbuscular mycorrhiza market: from arbuscules to common mycorrhizal networks," says this:

"Arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis is the fruit of a long coevolution of AMF {arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi) with their plant partners, in constant interaction with many other (abiotic and biotic) components of their environment; as such, it constitutes a major element not only of plant life, but also of agroecological production."

Otherwise, in the literature I find no mention of Ageratina brevipes being used by humans, though some Ageratina species are known as such. One reason may be the difficulty of distinguishing the numerous Ageratina species. Just in the neighboring state of Hidalgo, 37 Ageratina species have been documented.

However, I can report that during this drought when even honeybees are seldom seen, a few were busy among our shrub's flowers. Also, if my guess about our shrub participating in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis is correct, in an ecological sense, this flowering citizen of its little livestock-overlooked ecosystem may have been at the heart of a worthy community struggling to keep its patch of the Earth intact.