Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the April 28, 2007 Newsletter issued from Sierra Gorda Biosphere Reserve, QUERÉTARO, MÉXICO

AQUICHE AT ITS UGLY TIME

Early this week I accompanied a group of foreign visitors on a late-afternoon hike down the reservoir road. One plant that really got that group's attention was the Aquiche. For one thing, Aquiche is probably our second-most abundant roadside tree, after the Sweet Acacia. For another, people just couldn't believe a tree could look so disheveled and ugly. The poor scraggly thing was mostly leafless, with only a few tattered, faded, bug-eaten leaves giving it a hang-dog look, and then it was absolutely loaded with black, bumpy-looking, hard, scratchy fruits. You can see what I'm talking about below:

You can see a close-up of some fruits in my hand below:

Actually, I've told you about Aquiche before, because also back in the Yucatan this was one of the most common roadside "weed trees." In the Yucatan the Maya call it Pixoy, and in other parts of Mexico it's often called Guácima. It's GUAZUMA ULMIFOLIA, a member of the same family the Cacao tree of chocolate fame belongs to, the Sterculiaceae.

Beneath many Aquiche trees nowadays the ground is thick with black fruits. When you approach such a tree on a hot, sunny day a strong honey odor hangs in the air. That's because the fruits are very slightly sweet. In sunlight you can see "honey droplets" glistening in cracks between the fruits' bumps. In fact, when you're real hungry you can actually eat the fruits, being careful not to break a tooth. Here Nature has done a masterful job making a fruit that's too hard for most animals to fool with, but just sweet enough to entice someone every now and then to gnaw on one. It's a lot like eating the crusty backbones of Honeylocust fruits. On the Internet I find a report of White-faced Monkeys eating Aquiche fruits in Costa Rica, but only infrequently.

Livestock eat the leaves and workable fiber can be drawn from the branches. My "Plantas Medicinales de Mexico" says that traditionally the tree's bark was used to cure malaria, skin diseases, elephantiasis, leprosy and other ailments.

Some trees loaded with fruits already bear little yellow flowers. Apparently it takes about a year for those tough fruits to mature.

from the June 5, 2016 Newsletter issued from Hacienda Chichen Resort beside Chichén Itzá Ruins; limestone bedrock; elevation ~39m (~128ft), N20.675°, W88.569°; central Yucatán state, MÉXICO

PIXOY'S PRETTY FLOWERS

One of the most common, most useful and most scrappy-looking trees in all of Mexico is one lacking an accepted English name, and in Mexico known by at least 20 local names. In Querétaro we called it Aquiche. Among Tzotzil speakers in Chiapas it was something like Tzuny, and here among the Maya it's Pixoy. It's GUAZUMA ULMIFOLIA of the Hibiscus Family, the Malvaceae. Here as the dry season breaks into the wet season, the Pixoys are flowering, and the blossoms are as attractive and interesting as the dry-season-fruiting trees are inelegant. A shot of the tree's elm-like leaves and terminal panicles of small flowers appears below:

A single 5-6mm wide (1/5-inch) flower is shown below:

In that picture the pale green items at the blossom's bottom are sepals, of which usually there are three -- in some other flowers only two. And, at that point, this flower's anatomy starts getting interesting.

For, we assume that the slender, brownish items extending from the goblet-shaped, yellow corolla are stamens. However, look at what you see when you break open a blossom for the longitudinal view shown below:

In that picture, the brownish items arise from the tips of curved-inwards petals, not at the ovary's base like decent stamens. The forked, brown, stamen-like things are just sterile appendages of the corolla arising above the petals' lower halves. Also in the above picture you can see the real stamens, with their yellowish anthers atop purplish filaments, all clustered around the hidden ovary,. Also visible is the pale little style in the cluster's center, sticking up like a curvy worm. And, notice how the anthers snugly fit into little notches formed where the petals' appendages connect with the expanded, yellow parts below. This flower is just full of surprising little elegances.

At this point, certain features of recent taxonomy start making sense. In the old days, Guazuma ulmifolia was assigned to the Chocolate or Cacao Family, the Sterculiaceae. But recently that family has been lumped into the huge Hibiscus Family, famous for its flowers having several to many stamens united at their bases into "columns" around the female pistil. In the above cross section we can see that the stamens are indeed joined into a cup-like column at their bases. More interesting details are revealed when we move deeper into a flower's center, shown below:

In the blossom's center we can make out the pinkish ovary topped by its short, slender, curved style -- which the anatomists assure us is actually five styles fused together. In fact, if you look closely you can barely see long fissures in the object, which must be where the styles connect with one another Also notice that the ovary's base is immediately surrounded by a crown-like collection of short, pointed, hairy, yellow staminodia, which are sterile, modified stamens.

By the time I'd absorbed all these details, I was almost breathless, especially in the day's heavy heat. However, this Guazuma ulmifolia, so often despised for its commonness and lack of pizzazz, surprised me yet more by displaying tiny, green, globular growths along its leaf margins, shown below:

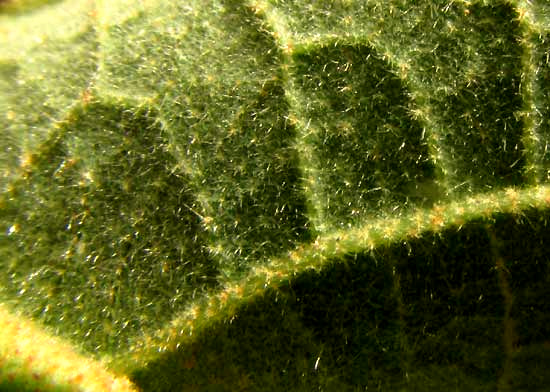

I guess that those are galls, maybe nipple-galls produced by tiny insects whose larvae will feed on them when they hatch inside them, but who knows what they are? And while I was at it, I admired the leaves' velvety bottoms so softly covered with hairs that often were "stellate" or star-shaped, as shown below

Finally, Guazuma ulmifolia is so useful to humanity that it's being planted in tropics worldwide, wherever there are strongly defined dry and wet seasons, as here. The WorldAgroforestry.Org website page detailing the species' use as firewood, in charcoal production, as food, fodder, for honey production, and as medicine (diarrhea, dysentery, venereal diseases, colds, coughs, diuretic, astringent... ) is available in PDF format here.

from the December 6, 2009 Newsletter issued from Hacienda Chichen Resort beside Chichén Itzá Ruins, central Yucatán, MÉXICO

FIBER FROM THE PIXOY TREE

Back in Querétaro (above) I introduced you to the Aquiche tree, called Pixoy here, and I remark that traditionally the tree's bark was used to cure malaria, skin diseases, elephantiasis, leprosy and other ailments, plus that fiber was drawn from its branches. This week in preparation for making a special ceremonial dish I got to see how those fibers are extracted.

A Pixoy grew less than 20 feet from where the fibers were needed. Don Paulino simply walked over to a Pixoy and macheted off some six-foot lengths of "water sprouts," Water sprouts are those fast-growing, straight sprouts that sometimes emerge at the base of a tree and shoot up through the tree's older, much-branched limbs. The sprouts were about as thick as a banana, so they were pretty substantial.

Then Don Paulino and his helpers set about beating the poles against old tree-stumps or pounding them with rounded rocks, but not hard enough to crack the bark. I assume that this helped loosen the bark from the wood. Then each man planted a stick before him and began pulling strips of semi-pliable bark off, each strip an inch or two in width. Once the strips were removed they were still pretty stiff so they needed to be worked to soften up. You can see how this was done below:

You can see how the fibers were used to tie a stack of special tortillas wrapped in fronds of Chit palm before they were baked in a ground pit below:

from the April 24, 2011 Newsletter issued from Hacienda Chichen Resort beside Chichén Itzá Ruins, central Yucatán, MÉXICO

HONEY-SMELLING MORNINGS

Especially because the afternoons can be so awfully hot, nowadays morning hikes are especially pleasant. This week they've been even more agreeable because the whole landscape -- at least in early morning when sunlight starts warming things up and the wind hasn't started blowing -- has smelled a lot like honey.

It took me awhile to figure out where the honey odor was coming from. It was from abundant, hard, black, bumpy, mothball-size fruits lying on the ground fallen from Pixoy trees, as the Maya call them. I made a longitudinal section of a fruit, which revealed speckled, beanlike seeds inside their cozy chambers. Atop each chamber arose a black, woody "tubercle," which glistened in sunlight. Best I could determine, the tubercles' glistening stuff is sweet and smells like honey. You can see all this below:

In fact, if you have solid teeth, you can eat Pixoy fruits. They're just sweet enough to create an interest, but otherwise they're so hard and crunchy that few humans would want to eat them, other than as a novelty. I read that deer like them. Pixoys are abundant trees here where forests are growing back after being destroyed, so I can easily imagine deer and other browsers walking around and "sowing" innumerable, very hard Pixoy seeds in their poop.

from the January 22, 2012 Newsletter issued from Hacienda Chichen Resort beside Chichén Itzá Ruins, central Yucatán, MÉXICO

HUNGRY SQUIRREL

Nowadays on most early mornings just as the sun breaks over the horizon an endemic Yucatan Gray Squirrel, SCIURUS YUCATANENSIS, climbs into a tree near the hut and perches awhile nibbling fruits, as shown below:

The tree he climbs is an abundant, almost-weedy species that in most of Mexico is called Guácima, though in Querétaro we knew it as Aquiche, and the Yucatán Maya call it Pixoy. It's Guazuma ulmifolia of the Cacao (Chocolate Tree) Family, the Sterculiaceae. Nowadays because of the dry season many Pixoys have lost nearly all their leaves, but their branches still bear abundant, marble-sized, semi-woody, bumpy-surfaced fruits. The tough fruits contain just enough sweet goo to entice anyone with a sweet tooth to gnaw into them, thus freeing the seeds for dispersal.

So, what's the story here? The story is the mere fact that a Yucatan Gray Squirrel is being documented eating fruits of Guazuma ulmifolia. Down here relatively little fieldwork has been done on most plants and animals, so such documentation is valuable to future ecologists and book writers trying to piece together the life histories of organisms found here.

To that future investigator... here it is!