Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the March 29, 2015 Newsletter issued from Río Lagartos, on the Yucatan Peninsula's northern coast (~N21.60°, ~W88.16°), Yucatán state, MÉXICO

"MUD WEED"

During this half year at Río Lagartos I've spent a lot of time identifying plants and animals. Imagine my frustration that during that time I've been unable to name one of the most dominant and conspicuous of all organisms occurring here. To get a feeling for the enormity of this failure, take a look at the aerial photograph of the western side of Ría Lagartos Estuary shown below:

In that image, the blue Gulf of Mexico occupies the top, left corner. A slender finger of land separates the Gulf from the estuary that parallels the Gulf just inland. Río Lagartos is the white, pyramid-like presence near the picture's top, right corner, projecting into the estuary. The similar, upside-down-pyramid at the lower left is San Felipe, and connecting the two towns at the picture's bottom is the coastal road I bike on days I don't have tours.

The dark-banded expanse of estuary between Río Lagartos and San Felipe is what concerns us here, for the dark bands coincide with submerged beds of almost pure stands of a felt-like, ropy and often lobed alga. You can see the alga as it appears in clear water when looking over the side of a boat -- its green, paddle-shaped lobes heavily coated with natural, calcium-carbonate-rich marl -- at the top of this page.

In this area it's easy enough to reach over the boat's side and pull up irregularly formed lobes and stringy strands of the alga, as shown below:

Another shot, showing flat pads budding from thick, cylindrical strands that behave like rhizomes creeping through the mud is shown below:

Under certain conditions, the pads "bud," into interesting formations, as seen below:

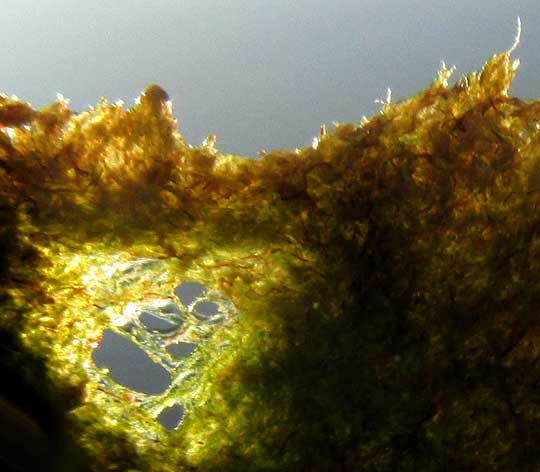

The alga feels like wet felt, and when the pads are pulled apart you see that the pads and cords are all composed of what appear to be tiny, green filaments, though they're branched as shown below:

We've identified several alga species here whose complex-looking bodies proved to be composed of such networks of tiny, branching tubes, with the tubes themselves lacking cell walls, so that cell nuclei, chloroplasts and other organelles migrated throughout them in such a way that the whole, large body was considered just one cell. Such organisms with free-roaming nuclei and organelles are known as "cenocytes." And now I know that our mystery alga is cenocytic, too, for finally I found someone who could simply tell me what the alga is.

My biologist friend Willie told me about Dr. Ileana Ortegón-Aznar, head of the department of Tropical Marine Resources at UADY, the Autonomous University of the Yucatán. Dr. Ortegón-Aznar identified our alga as a species of the genus AVRAINVILLEA*.

Species of Avrainvillea belong to the alga order Caulerpales, in which algal bodies are composed of filaments that somehow, mysteriously, organize themselves into much larger bodies that behave like leaves, stems and roots of flowering plants -- just as our Avrainvillea does.

Dr. Ortegón-Aznar says that Avrainvillea is common in this area, and that although it often grows in areas of high nutrient content and/or much organic matter, its presence here is not necessarily an indication of polluted water.

However, I hypothesize that the vast area of Ría Lagartos Estuary so totally dominated by Avrainvillea got that way because about forty years ago, right across from Río Lagartos, a canal was cut through the slender finger of land separating the Gulf from the estuary. I bet that the canal caused the area currently occupied by Avrainvillea to lose its ability to "flush" with changing tides. Now very much of the estuary's tidewater streams through the canal, leaving relatively "dead water" covering our Avrainvillea prairie.

Despite the dominance of Avrainvillea in this dead-water area, this part of the estuary is not an ecological desert. Diego says he sees lots of creatures there, including many Tarpon, which wouldn't be there if they didn't have something to eat. The canal may have drastically altered the population structure of that part of the estuary, but it didn't kill it.

Still, I find mention of an invasive Avrainvillea species taking over certain areas of shallow water in Hawaii, with such drastic effect on local species diversity that efforts are made to physically remove it. Also, nowadays another member of the order to which Avrainvillea is assigned, Caulerpa taxifolia, is invading much of the Mediterranean with negative effects on biodiversity. Therefore, our Avrainvillea has relatives who can be mean and aggressive, so it's not beyond question that our local Avrainvillea may be doing nasty things, too. But, all this is just conjecture.

In Hawaii where an Avrainvillea species is causing trouble, folks sometimes refer to their invasive species as Mud Weed. I think that that's a good name for it, since here our Avrainvillea grows in mud, and normally is so heavily coated with carbonaceous marl that one wonders how it survives.