Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

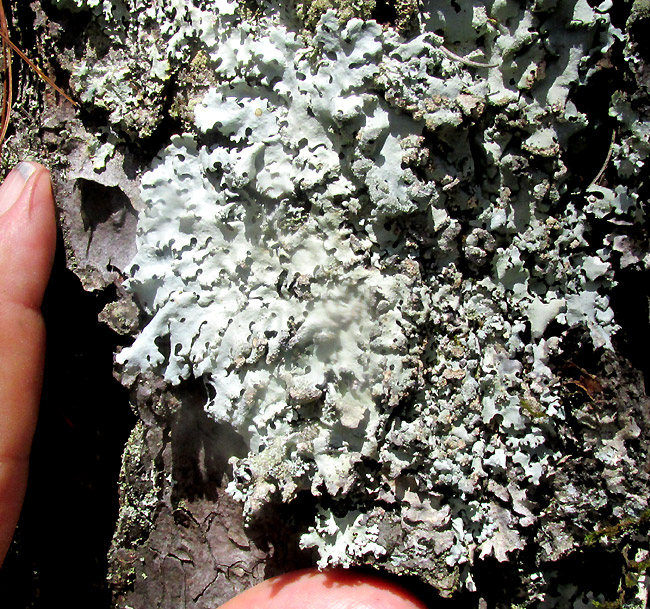

Entry from field notes dated September 2, 2023, taken in Los Mármoles National Park in the Eastern Sierra Madre mountains, Hidalgo state, MÉXICO; oak-pine forested mountain peak about 3km west of Puerto de Piedra, on road branched off the road between Trancas {on maps designated "Morelos (Trancas)"} and Nicolás Flores; limestone bedrock; elevation ~2,650m (~8,700ft); N20.816°, W99.214°

CRACKED RUFFLE LICHEN

The night immediately after the above picture was taken, clouds enshrouded our wooded mountain peak. Though the resulting fog glowed from the full moon, through the drifting mist I couldn't see more than two or three tree trunks around the tent. All night, condensed water droplets fell, soaking the tent and the forest floor. In this habitually moist environment, many lichens covered tree trunks, but the above species, on a pine's bark, especially caught my attention. With its large size and the white thalli's broad surface areas, it simply showed up more than all the rest.

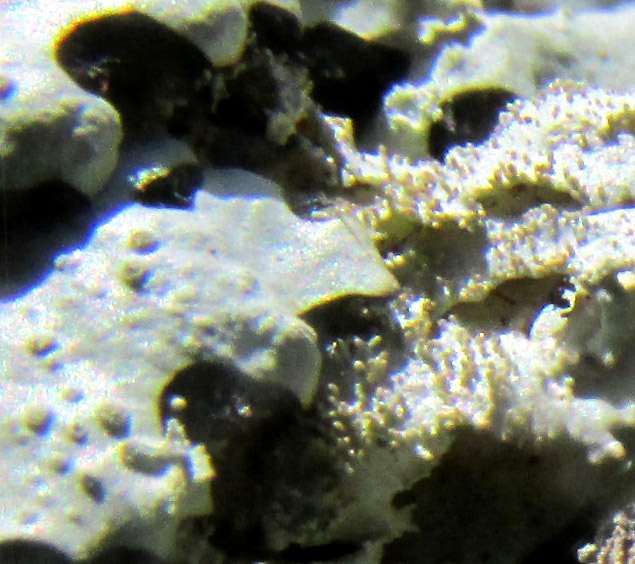

Up close, another unusual detail was that the sinuses between thallus lobes were broadly rounded, as if cut with an office hole-punch. Thalli on one side of the colony were smooth and practically void of reproductive structures, but the other side in places acquired dense concentrations of tiny, wartlike soralia.

Soralia, which can be of various forms -- ours were warty -- are a means of nonsexual, vegetative reproduction. When soralia disintegrate, the resulting powdery grains are called soredia. Soredia consist of alga and/or cyanobacteria cells enmeshed amid fungal hyphae. Wherever a soredium ends up, if environmental conditions are just right, it can make a new lichen.

At the right, two kinds of warty structures are visible. I'm assuming that both are soralia, since the technical description of the Consortium of Lichen Herbaria page says that on this species isidia, which are very small fingerlike structures, are absent.

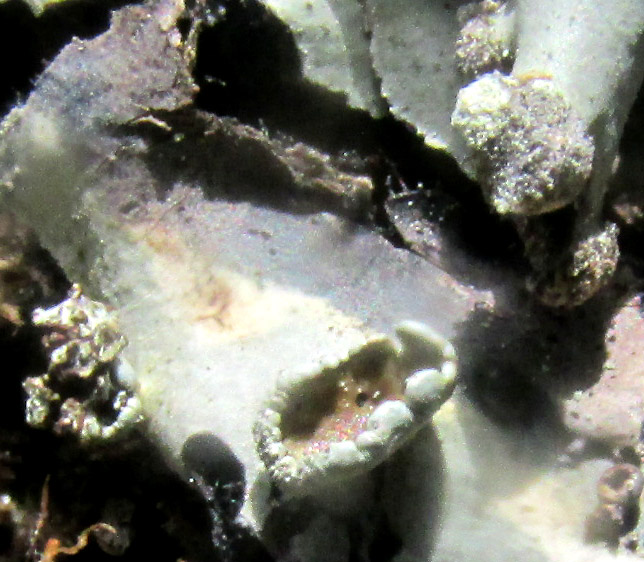

Above, the cuplike item at the picture's bottom is a spore-producing apothecium, the only one in the colony. Its cracked and soralia-bearing rim, its irregular shape and rare occurrence all seem to be typical of the species. Above the apothecium, in the darkly shadow area, note the hairlike rhizoids issuing from the bottom of an upturning thallus. Here's a better view of a thallus's lower surface:

Important field marks include that the undersurface is black, but brown areas occur beneath older thalli, and the patches of hairlike rhizoids display varying lengths. Near thallus margins black may give way to white.

The above features point to the genus Parmotrema, the ruffle lichens. When expert-identified images are viewed of Parmotrema lichens documented in this part of upland central Mexico, the only species looking like ours with its hole-punch sinuses is PARMOTREMA RETICULATUM which, among several common names used for it, often is known as the Cracked Ruffle Lichen. When its thalli dry, cracks develop. Our lichen, used to moistening during its nights in cloud-fog, isn't cracked.

Parmotrema reticulatum occurs worldwide, mostly on trees, and is common in so many habitats that one suspects various species may be involved.

During studies for her 2020 thesis at Mexico's Autonomous National University in Mexico City, Beatriz Quiroz Allende studied the medicinal use of fungi in Mexico's Puebla state. For her thesis entitled "Conocimiento Tradicional y Uso de Hongos Medicinales en Cinco Localidades de La Sierra Norte de Puuebla, México," Parmotrema reticulatum was found to be used for curing skin lesions, particularly bumps caused by insect bites.

The 2016 study by A.P. Jain and others entitled "Evaluation of Parmotrema reticulatum Taylor for Antibacterial and Antiinflammatory Activities," found that in lab experiments significant "... antiinflammatory effects at 200 and 300 mg/kg dose of acetone and ethanol extracts..." resulted from the controlled use of Parmotrema reticulatum.

The 2014 work of Preeti Shukla and others entitled "Natural Dyes from Himalayan Lichens" demonstrated that for silk threads a rich, dark-brown dye could be gained from Parmotrema reticulatum using the ammonia fermentation method, as well as a paler milk-chocolate color using boiling water.