Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the March 22, 2015 Newsletter issued from Río Lagartos, on the Yucatan Peninsula's northern coast (~N21.60°, ~W88.16°), Yucatán state, MÉXICO

PRINCEWOOD

Part of the joy of being in an area of high species diversity is that you never know what spectacular organism will greet you around the next corner. A big surprise this week in the thorn forest was a 15-ft-high (4.5m) tall tree I'd passed many times without noticing but which this week attracted attention with its large, white flower clusters. The tree's general form couldn't be made out because its branches were so entangled with those of other trees and bushes, but below you can see a typical branch with snowy inflorescences handsomely set amid dark green, glossy, simple leaves:

Despite the tree's impressive appearance, I had no idea what it could be, and so needed to "do the botany." The flowers were too high to examine closely but from the ground it could be seen that the blossoms were arranged in panicle-type inflorescences -- panicles having branches off their main axes themselves branched -- as shown below:

With the camera's modest telephoto ability and by pushing PhotoShop to its limit, a shot was obtained of a single flower with six corolla lobes -- contrasting with most flowers having only five lobes -- and a similar number of stamens, and a yellow, four-divided style, as seen below:

Mingled among the flowering clusters were other clusters of brown items, which I assumed to be fruits. A blown-up picture of these things proved that they were otherwise, as shown below:

The brown, papery, 5-lobed item at the picture's top, left corner best shows that the brown things actually were corollas that as they aged dried and turned brown, retaining the corolla's original shape. Below the tree the ground was littered with discarded corollas, some of which are shown in my hand below:

The corolla at the image's top, right corner retains a few shriveled stamens. The two corollas at the left show objects attached at their bases which at first glance one assumes to be hairy fruits. However, if one of the hairy things is torn open it's discovered to be a dried-up calyx enclosing a fruit.

The tree's whitish trunk bearing termite tunnels leading between the ground and upper branches is shown below:

Features of flowers and fruits led me to the Borage Family, the Boraginaceae, which most Northern gardeners think of as a family consisting mainly of herbs -- Borage, Hounds-Tongue, Bluebells, Forget-me-not -- but which in the tropics produces fair-sized trees. Knowing our tree's family, it was easy to discover our tree's identity by scanning the list of Borage Family members occurring in the Yucatan.

Our pretty tree is CORDIA GERASCANTHUS, sometimes known in English as Princewood or Spanish Elm, though it's not closely related to elms at all. The name Princewood reflects people's appreciation of the wood's beauty, workability and durability. Princewood occurs in arid environments, especially on limestone, from southern Mexico and the Caribbean south to northern South America.

This is the second tree we've encountered here whose main English name appears to be Princewood. The two trees are not closely related, but that's how common names work: Just about any tree whose name is highly admired might be called Princewood by someone.

from the March 4, 2018 Newsletter issued from Rancho Regenesis in the woods ±4kms west of Ek Balam Ruins; elevation ~40m (~130 ft), N20.876°, W88.170°; north-central Yucatán, MÉXICO

PRINCEWOOD #2 FLOWERING

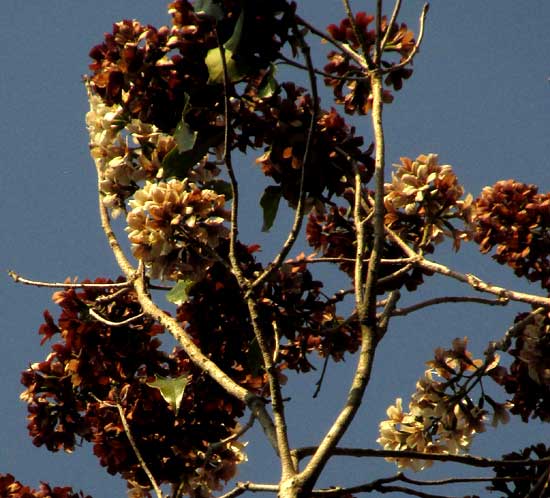

A tall, well formed, commonly occurring tree has been flowering in our area, sometimes so heavily laden with dense clusters of ½-inch broad flowers that the trees looked like big snowballs. The snowball effect lasts only briefly, though, because upon pollination -- and pollinators crave this tree -- the flowers' corollas quickly turn brown and papery, and fall off, leaving the ovary on the tree to mature into a fruit. Below, you can see a heavily flowering branch bearing both white and brown flower clusters:

A shot of a brown cluster right next to a white cluster is shown below:

In these images you can see that most of the tree's leaves have fallen, to cut down on water evaporation. However, other trees, especially those too young to flower, often retain their leaves. Some leaves have been on their tree for so long that crustose lichens splotch their blades, as shown below:

Up close, the most striking unusual feature about the flowers' anatomy is their slender, yellow-green styles tipped with four spherical stigmas, as seen below:

The flowers' calyxes are deeply cylindrical, with sepals that turn brown like the corollas, as seen below:

To help with the identification, a blossom cut down the middle shows the spherical, superior ovary at the corolla's bottom, seen below:

Finally, the tree's bark is shown below:

You'd think that such a handsome, commonly occurring tree with so many distinctive features would be easy to identify, but there are challenges...

*UPDATE: With Internet resources available in 2018, based on differences in stigma shape I read about in the literature, I thought that this tree probably was different from the Cordia gerascanthus profiled above, and called it Cordia alliodora. However, in 2024, when I upload this page's images to iNaturalist, user "robhertnandezc" recognized our images as the same species seen in Río Lagartos, Cordia gerascanthus.

In 2024 when I look into more recently available literature and images on the Internet, I tend to agree with "robhertnandezc." Also, the distribution maps on CICY, the main scientific in the Yucatan, now shows the species I earlier thought we had, Cordia alliodora, as present in the Yucatan Peninsula only in Campeche and Qintana Roo, not this far north in the Yucatan.

from the December 21, 2018 Newsletter issued from Rancho Regenesis in the woods ±4kms west of Ek Balam Ruins; elevation ~40m (~130 ft), N20.876°, W88.170°; north-central Yucatán, MÉXICO

JUAN'S AX HANDLE

One morning this week I found Juan, one of the rancho's workers, using his machete to fashion an ax handle from a slender section of tree trunk. Below, you can see the operation :

The wood was exceptionally heavy and compact, and its grain was straight. When I asked Juan what tree he'd cut for the handle, he gave the Maya name of Bojum (bo-HOOM). Since I didn't know what a Bojum was, he took me to a medium-sized tree passed each time I go to the garden. It was the same tree we've featured flowering above.

There our pictures show the tree handsomely laden with flowers last March. But now in December all that remains of that flowering are some brown, withered, finger-long, dried-up raceme stems with old flower pedicels, as shown below:

Last March the flowers so dazzled me that I hardly noticed the tree's leaves. Now I noticed that the leaves exhibited interesting features. For example, their blades tended to be spotted with lichen patches, and the older ones curled. Also, their petioles were exceptionally long, as you can see below:

The leaves' bases were consistently asymmetrical -- attaching to the petiole at different places, as seen below:

The long petioles themselves were unusual in that they took on the color and corky texture of the surface of the twigs they were attached to, as shown below:

The leaves' blades were thick and leathery, with the veins not showing very well, but if held against the Sun the venation showed itself to be of that kind whose secondary veins curve forward to connect to the secondary veins above it, as illustrated below:

I had wondered why this species was called Princewood, and now Juan with his ax handle -- which turned out to be a fine one -- has shown me. The tree simply produces wonderfully strong, regularly formed wood.

Those who know Temperate Zone plants might find it surprising that this imposing tree belongs to the Borage Family, the Boraginaceae, for up north the best-known species in that mostly herbaceous family are such wildflowers and herbs as bluebells, forget-me-nots, gromwell, comfrey, heliotrope and hounds-tongue. In the tropics, plants often behave very differently from their temperate-zone relatives.