Excerpts from Jim Conrad's

Naturalist Newsletter

from the September 28, 2018 Newsletter issued from Rancho Regenesis in the woods ±4kms west of Ek Balam Ruins; elevation ~40m (~130 ft), N~20.876°, W~88.170°; central Yucatán, MÉXICO

BONELLIA BUSH FRUITING

A fruiting, eight-ft-tall (2.5m), shrub or small tree has turned up fruiting along one of the rancho's cow trails through the woods. Below, you can see the plant's green, lemon-like fruits and leathery, willow-like leaves:

I had no idea what it was, so began looking for good identification features, though without flowers I didn't have much hope for success. One of the first features that caught my attention was that the leaves were sharp-pointed at their tips, as shown below:

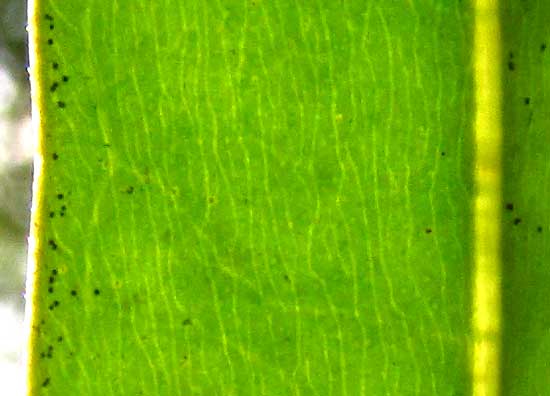

While looking at that hard, dark little spine at the leaf's tip with a hand lens, I noticed that the leaf's venation also was curious. A few weakly defined, widely spaced secondary veins broke off the midrib in the regular way, but also the leaf body contained many indistinct lines running more or less parallel with the midrib, apparently independent of the secondary veins. Holding a leaf up against the Sun revealed the patterns seen below:

We've seen bright points and short lines -- "pellucid" structures -- in leaves before, but nothing like this.

So far I was drawing a blank about this plant's identity, but maybe the fruits would show something special. Looking at the fruits, it was noticed that often they appeared in pairs, and that their fruit stems joined a flowering stem from which flowers had fallen, as shown below:

This indicated that the flowering structure, the inflorescence, had been a raceme -- one with a central axis on which flowers on little stems, or pedicels, were borne. This was an important detail.

Breaking the top off one of the immature fruits revealed what's shown below:

Well, this is something special. Those pale yellow, beanlike items on the side of the waxy, orangish item occupying the fruit's center are immature seeds. They don't appear to be attached to the fruit's central core, like normal seeds in an apple or tomato, nor even to the fruit's exterior wall, as in a papaya. Now a fruit was cut from top to bottom, revealing what's seen below:

The whitish item on the orangish item's side is an immature seed, and it clearly isn't attached to the wall, nor does the orangish item display a central core like a normal fruit. When the orangish item was nudged from the husk, the developing seeds' points of attachment became clear, as shown below:

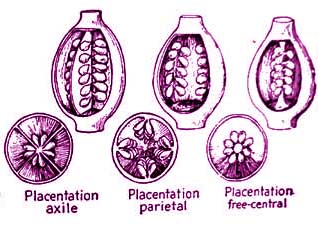

Ovules in flower ovaries, and the developing immature seeds that come later, are attached to the ovary or maturing fruit by a "funiculus," the plant equivalent to an umbilical cord. The part of the ovary or developing fruit to which the funiculus attaches is called the placenta. Among flowering plants, the placenta's structure is distinctive from family to family. If you find a plant with unusual "placentation," then you've found something special. And our cow-path bush's fruits displayed very unusual placentation.

Our plant's placentation is described as "free-central with ± globose (spherical) central axis," and such placentation is found in only a handful of plant families. You might find it interesting to compare what we've seen in the above photos with my altered photo of a drawing in my old Bailey's "Manual of Cultivated Plants," shown below:

At the very helpful online Plant Families of the World Identification Key, our plant's amazing placentation and the few other details noted above were enough to introduce me to a plant family I'd never met before, the mostly New-World tropical THEOPHRASTACEAE, which I suppose to be known as the Theophrastus Family. According to the online Flora of North America, members of the Theophrastaceae are "often evergreen, usually glandular-punctate or with secretory resin canals appearing as dark dots or streaks... " which sheds light on those strange, shiny lines shown in our leaf close-up.

Once the family was known, it was easy to compare our pictures with those of the few members of the Theophrastaceae listed for the Yucatan. Our plant is a member of the genus Bonellia

Three or so Bonellia species are listed for the Yucatan. Our plant matches images of BONELLIA MACROCARPA, but the other species are so little documented and scantily described that I can't be completely sure that we have the species macrocarpa . Bonellia macrocarpa is by far the most commonly documented here, and I feel maybe 90% sure that that's what we have.

Bonellia macrocarpa is native to Mexico, the Caribbean area and Central America south into Honduras, growing in what the online Flora of North America calls thorn scrub, though our vegetation is a little lusher and taller than what I think of as scrub. The Flora of North America profiles it because it has escaped around Miami in Florida, finding a home in spoil deposits and fringes of mangrove forest. No English name is give for it, though in Spanish it's called "Pico de Gallo (Rooster Beak, for the sharp-pointed leaves), Limoncillo (Little Lemon), and Naranjillo (Little Orange). The fruits are eaten by wildlife but not humans. Sometimes the plants are grown as ornamentals.

from the November 9, 2018 Newsletter issued from Rancho Regenesis in the woods ±4kms west of Ek Balam Ruins; elevation ~40m (~130 ft), N~20.876°, W~88.170°; central Yucatán, MÉXICO

BONELLIA FRUITS RIPE

This week the same bush profiled above bore fully mature, bright yellow fruits, and I can't explain why animals haven't taken them. Whatever the case, when one of the lemon-like fruits was broken open, its dark brown seeds encrusting a large ball of freestanding, waxy substance seemed like something worth showing. You can see below: