Hernando de Soto, 1500-1542; image from 1881 Young Peoples' Cyclopedia of Persons and Places

Hernando de Soto, 1500-1542; image from 1881 Young Peoples' Cyclopedia of Persons and PlacesOn May 28, 1539, the Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto landed with an army of 620 men and 223 horses in Florida, probably not far from Tampa Bay. These were not the first Europeans to visit the North American mainland, but as far as is known they were the first destined to visit our Loess Hills.

When de Soto landed, he was still uncertain as to whether Florida was just another swampy island of the type the Spanish had found so many in the Caribbean, or whether it might be, as rumor suggested, a land of wealthy indigenous communities ripe for being robbed of prodigious quantities of gold, silver, and jewels.

More than anything, de Soto wanted to be like his fellow Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés, who recently had made a name for himself and grown rich by destroying and plundering the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan in central Mexico, in 1521. And more recently, Francisco Pizarro, through treachery and sheer barbarism, had robbed the riches of the Peruvian Incas in 1532.

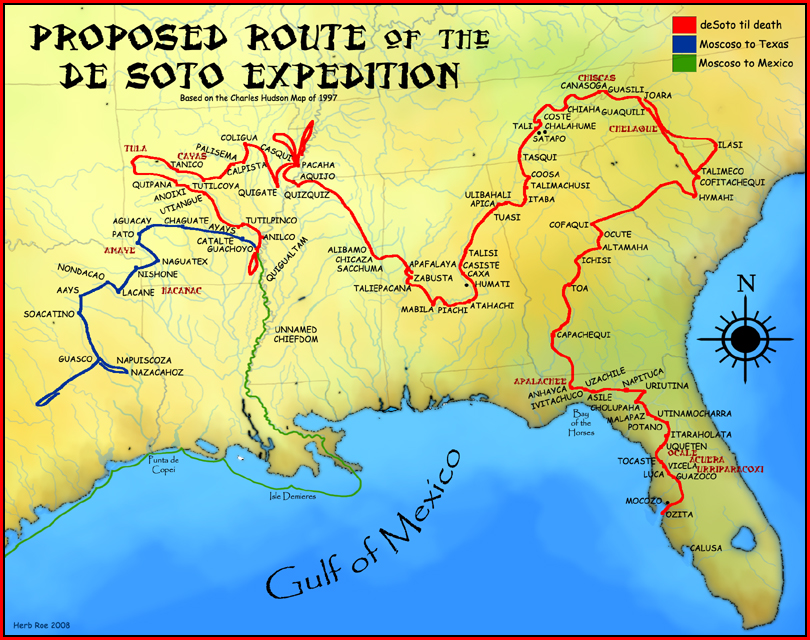

However, the main riches de Soto and his army found as they marched north through Florida, and then for the next three years followed the route envisioned above, was a rich mosaic of native American cultures. The army would fight and bluster its way through a land of fairly prosperous farmers and hunters, a land thickly populated with fair-sized cities with impressive temples and traditions. In other words, the natives seem to have been doing fairly well for themselves.

The native Americans reacted to the aggressive army in various ways. Sometimes they tried to be friendly, more often as not getting rid of their unwanted visitors by insisting that just a bit beyond their own land there were far richer folk. Some tribes resisted the Europeans with all their might, at least for a while, before succumbing to the Spaniards' superior technology; Spears and arrows were arrayed against guns and armored men on horses. During the expedition's worst fight, at Mabila, Alabama, in 1540, one chronicler reported more than 3,000 Americans slain, with only eighteen Spaniards and twelve horses killed.

In the spring of 1541 the band fought desperate battles in northeastern Mississippi's Chickasaw country at Chicaca and Alabamo. The next significant event recorded by the chroniclers was their entry into the town of Quizquiz, sometimes written Quiz-Quiz, in northwestern Mississippi. Near Quizqui, de Soto and his men must have traversed our Loess Hills. Some think the ancient Provice of Quizquiz may coincide with what archaeologists call the Walls Phase of southwestern Tennessee and northwestern Mississippi.

The expedition's chroniclers didn't provide us with a single word about changes in vegetation around them reflecting the ever deeper loess beneath their feet, or the Loess Hills' deep, steep-walled ravines, or any precipitous drop into the swampy lowlands. Maybe the army was in such a bad shape after so many battles that such changes just didn't seem worth their attention. Recently they had lost most of their clothing and weapons in a fire set by the locals.

"The half-naked, wild-looking, foul-smelling Europeans with their battered and makeshift weapons must have seemed to be monstrous caricatures of human beings to the well-fed, well-clothed, civilized residents of the province of Quiz-Quiz," suggests historian Mary Ann Wells in her book Native Land: Mississippi 1540-1798.

From Quizquiz, de Soto and his band headed northwest until on May 8, 1541, a few miles downriver from present-day Memphis, they "discovered" the Mississippi River, which local folks had lead them to. The army crossed the river and continued wandering somewhat erratically through Arkansas, until they turned back to get to the Mississippi River. De Soto died there 1542, of illness.

Leadership of what remained of the army was taken over by Louis de Moscoso Avarado. Moscoso then led his men on more wandering through Arkansas and into Texas, at which point it was decided to return to the Mississippi. During the winter they built seven small ships with which they then sailed down the Mississippi. Eventually they reached the Gulf of Mexico, and finally found Spanish support in Mexico itself.

What were the lasting effects of the de Soto Expedition? Surely they were profound, for the Spaniards had left a trail of disease wherever they had passed. A better planned campaign of "germ warfare" against America's native population could not have been better put into action. North Americans did not possess natural immunities for the diseases the Europeans brought with them. When the next wave of Europeans entered our area, about a century later, they found the human landscape profoundly reduced, with entire indigenous societies missing or much degenerated since de Soto's passage.