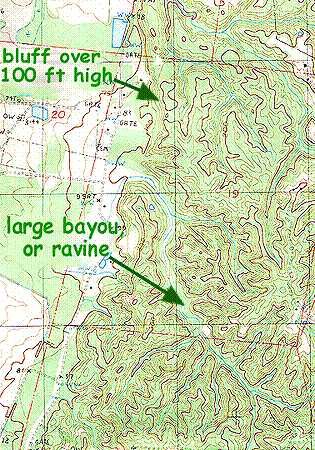

At the right, a topographic map shows an area just south of Natchez, Mississippi, where the Loess Hills meet swampy bottomlands along the Mississippi River's eastern banks. The left part of the map with relatively few elevation lines is low and fairly level, while the right part with many lines is the nearby hilly upland.

All along the bottomlands' eastern side, a steep bluff forms the transition between swampland and upland. The brown lines signify intervals of 20-ft change in elevation, so the heavier brown lines represent 100 ft intervals.

LOESS DURING THE CIVIL WAR'S SIEGE OF VICKSBURG:"

In 1863 when Union forces under U.S. Grant besieged Vicksburg, loess played a vital role. Union shells sent over Vicksburg's walls buried themselves in the loess without going off. However, Union soldiers found they could easily tunnel through the loess to plant bombs beneath the town's walls, opening the walls so that Union soldiers could enter. After the siege, General Grant toured inside Vicksburg, and in his book Memoires..... reported the following:

"The ridges upon which Vicksburg is built, and those back to the Big Black, are composed of a deep yellow clay of great tenacity. Where roads and streets are cut through, perpendicular banks are left and stand as well as if composed of stone. The magazines of the enemy were made by running passage-ways into this clay at places where there were deep cuts. Many citizens secured places of safety for their families by carving out rooms in these embankments. A door-way in these cases would be cut in a high bank, starting from the level of the road or street, and after running in a few feet a room of the size required was carved out of the clay, the dirt being removed by the door-way. In some instances I saw where two rooms were cut out, for a single family, with a door-way in the clay wall separating them. Some of these were carpeted and furnished with considerable elaboration. In these the occupants were Fully secure from the shells of the navy, which were dropped into the city night and day without intermission"

Grant's Memoirs can be downloaded for free.

With this in mind you can see that in some places the bluff rises over 100 feet (30m) in a rather steep slope, and that sometimes the elevation change from the swamp to the nearest hilltop is over 200 feet.

On the map, notice that the large bayou/ravine pointing to the map's bottom, right corner has very steep sides about 100 feet high, plus numerous "arms" branch off more or less at 90 degree angles. You can see that branching-off streams are fairly short, and their bottoms quickly gain elevation. They have steeply climbing bottoms.

Loess bluff near Vicksburg, Mississippi; image courtesy of Mark A. Wilson

Loess bluff near Vicksburg, Mississippi; image courtesy of Mark A. WilsonAn important point about the ravines not apparent on the map is that many, perhaps most, bayous, or ravines, instead of draining westward into the bottomlands by cutting through the bluff face, drain in the opposite direction, toward the east. At the map's top, right, the thin, blue lines are streams flowing eastward. However, the stream in the labled "large bayou or ravine" dominating the map's lower half, drains westward into the swamps. Water flowing in east-flowing streams drain into larger streams and rivers behind the bluff (on the eastern side), and then these streams and rivers typically, eventually, cut through the bluff someplace and flow into the Mississippi.

You might be interested in viewing this particular spot on a Google Maps satellite photo at approximately N 31º 28' 30", W 91º 25' 45".

"Sunken" section of historic Natchez Trace "caused by thousands of travelers walking over easily eroded loess soil," according to the National Park Service; image courtesy of Jan Kronsell

"Sunken" section of historic Natchez Trace "caused by thousands of travelers walking over easily eroded loess soil," according to the National Park Service; image courtesy of Jan KronsellAt the right, this preserved section of the original Natchez Trace, featured at Milepost 41.5 on the Natchez Trace Parkway, shows an interesting feature of loess: Trails and roads made on the easily erodible loess gradually erode into steep-walled, U-shaped gullies. Where the historical Natchez Trace passed among hills not capped with loess, slopes along eroded "sunken roads" were much less steep, and didn't develop into U-shaped gullies.

So, all this is curious. If you were to throw a dart at a map of the whole Earth, the chances are slim that your dart would land at a point within a hundred miles of such features as are shown on the topographic map and pictures.

Yet, that's not all. Sometimes embedded in the loess, or more likely eroded into the streams at the bottom of gullies, you find things like what's shown at the left. That's a very worn upper molar of the extinct mastodon Mammut americanum, found in a loess-zone bayou, or ravine, by amateur fossil-hunter Betty McKay of Natchez. Sometimes mastodons are called "mammoths."

At the right is another of Betty McKay's local finds, the upper cheek tooth of the large (the size of a big draft horse today, like a Budweiser Clydesdale) Ice-Age horse Equus complicatus. Thanks to Earl Manning of Tulane University for the identification of both of these specimens.