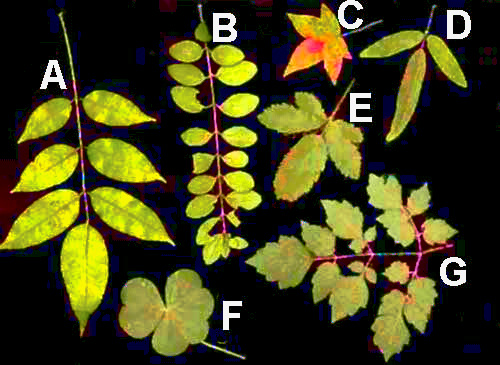

A key to really getting into plants is to know the identities of the plants you're dealing with. For plant identification, leaves can be helpful because each species has a particular kind of leaf. In the field, any visible feature helping us recognize the species we're dealing with is called a field mark. At the right, let's look at the field marks of several leaves collected during a brief walk.

Leaf A shows a single pinnately compound leaf of Hercules-Club, Zanthoxylum clava-herculis, bearing seven leaflets. However, Leaf B, from a Privet Bush, Ligustrum ovalifolium, seems to have the same general form, but actually a stem bearing about 20 individual simple (undivided) leaves. The Privet's many blades are identifiable as leaves on a stem and not leaflets of a leaf because at the base of each leaf's petiole there's a bud. At the base of each Hercules-Club leaflet, there's no hint of a bud.

Leaf C is a normal simple leaf not separated into distinct leaflets. It's the 5-lobed leaf of the Sweetgum tree, Liquidambar styraciflua, and lobes don't count as leaflets.

Leaf D, from a Tick-Trefoil, Desmodium sp., is another compound leaf, but it's compound in a different way. When compound leaves just have three leaflets, they're said to be trifoliate. At the left is another trifoliate species, Poison Oak, Toxicodendron diversilobum.

Leaf E is compound with five leaflets, but they're arranged differently than in compound Leaf A. In Leaf A, the leaflets arise along a rachis, which is the continuation of the leaf's petiole. However, Leaf E has such a short rachis that all five leaflets seem to arise from the same place. Leaf E is from a Dewberry, Rubus sp.

Leaf F, from the herb known in both English and Latin as Oxalis, is compound with three leaflets and there's no rachis at all. Leaflets arise from the top of the petiole like fingers, or digits, on a hand, so such a leaf is said to be digitally compound. At the right are digitally compound leaves of the tropical Ceiba tree, Ceiba pentandra. Leaves with leaflets appearing along the rachis, as in Leaf A, are said to be pinnately compound.

Leaf G is a compound leaf in which the lower leaflet sections are themselves divided into leaflets. Pinnately compound leaves with subdivisions that are themselves subdivided into leaflets are bipinnately compound. There are even tripinnately compound leaves. Leaf G is the bipinnately compound leaf of the Pepper-Vine, Nekemias arborea.

Margins of simple leaves, and leaflets of compound leaves, vary from species to species, as shown below on leaves collected during a brief walk.

Leaf A shows the crenate margin of the Swamp Cottonwood tree, Populus heterophylla.

Leaf B shows the spiny-toothed margin of the American Holly, Ilex opaca.

Leaf C shows the entire margin of a Greenbriar, Smilax sp.

Leaf D shows the shallowly lobed margin of an immature leaf of the Black Oak, Quercus velutina.

Leaf E shows the dentate margin of a wild grapevine, Vitis sp.

Leaf F shows the doubly toothed or twice serrated margin of the Eastern Hophornbeam, Ostrya virginiana.

Leaves also can bear tendrils which wrap around things for support. A pinnately compound leaf of Hairy Vetch, Vicia villosa, with its rachis ending with three tendrils is shown at the right.

Leaves can be hairless or hairy. Among hairy leaves, there's everything from slightly hairy to incredibly hairy, plus the hairs come in many sizes and configurations, as seen on our Hair Page. At left, that close-up is of a hairy leaf of the Mullein, Verbascum thapsus, with hairs that branch and fork.

Many species bear spiny leaves, such as those on the Purple Thistle, Cirsium horridulum, at the left.

This is just a hint of all the field marks leaves can have, so we'll end with one of the most amazing ones, shown at the right. That's a filamentous segment of a submerged leaf of the aquatic Bladderwort, Utricularia gibba. It bears a very small, bag-like bladder which, when an aquatic microscopic organism bumps into a hair, suddenly opens, water containing the animal rushes into the bladder, the animal can't get out, and eventually its nutrients are absorbed into the plant. In short, bladderworts are carnivorous plants.