IDENTIFICATION KEYS

KEY TO FIVE OBJECTS ON TINY PACIFIC ISLAND

A Object nonliving........................... B

AA Object living............................. C

B Object massive, irregularly shaped, opaque,

composed of natural minerals.............. ROCK

BB Object slender, artificially shaped, made

of transparent glass.................... BOTTLE

C Object rooted, with green leaves........ TREE

CC Object not rooted, with legs, no leaves... D

D Object feathered, able to fly........... BIRD

DD Object featherless, unable to fly..... HUMAN

Once the Martian uses the key to identify what's what -- once the Martian "keys out" those things -- the names be can looked up in the computer's Intergalactic Dictionary. Now, with all this in mind, here's a wonderful piece of news:

Identification keys -- real ones -- exist for helping identify nearly all natural things for which naturalists may want to know the names!

WHY BOTHER WITH KEYS?

Besides the usefulness of knowing the names of things, here's something great about using identification keys:

Using identification keys thrusts our minds into realms that previously we may have never even known existed, and this feels good...

For example, if someday you're keying out the wildflower shown at the right, maybe the key will ask you if your blossom bears both fertile stamens and sterile "stamenodia," or if the stamenodia are absent. In the picture, which seems to portrey a wonderfuland of fantastic forms, textures, color patterns and hidden meanings, a red arrow points to the fertile stamens covered with white pollen, and the yellow things are stamenoidia. Noting this, along with other information you supply, the key rewards you with the name Tripogandra amplexicaulis. That name can be looked up on the Internet, to see what's special about the plant. Is it edible? Medicinal? A source of dye or tough fibers? What's its role in its ecosystem? And this whole learning process, as it's happening, does feel good!

In fact, some would say that keying out plants and animals is nothing less than a form of meditation. It focuses, it intensifies our perceptions, it reveals, it calms, and it satisfies.

WHERE DO YOU FIND KEYS?

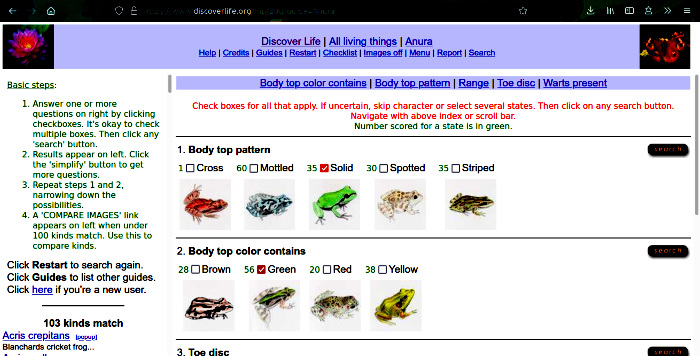

Many keys can be found on the Internet, and several are linked to in the KEYS section of our using-the-Internet page. Maybe the best collection of interactive online keys at the DiscoverLife.Org website. Below you see part of the DiscoverLife.Org's page providing the interactive key "Frogs & Toads, North America."

This key, unlike printed keys and the one used by our Martian on the tiny Pacific island, instead of asking a series of yes/no questions, enables you to plug in several characters at one time. On the above page, the characters "solid body top pattern" and "green body top color" have been entered. Note that near the image's bottom, left, the page shows that at the start of the query, with no characters reported, 103 frog and toad species were being considered. As features are entered and queries made, you can watch the number of possible names diminish. The goal is to keep describing more and more details until only one match is reported.

Technology is being to developed to allow us to photograph things with smartphones, resulting in a quick identification appearing on the screen. Currently it's fun to play with what's available and sometimes the ID is correct, but today's technology is far from being able to tell us which of the dozens of yellow-flowered daisy-like weeds or wildflowers we might photograph in our neighborhoods. Maybe later, but not yet.

Meanwhile, those with special interests should keep checking for every-more-advanced apps and online offerings. For example, take a look at Cornell Lab's 'Merlin program and app for North American bird identification.

Many books and scientific papers bear printed keys. Editions of "The Pictured-key Nature Series," such as the one at the right, are available for many groups of organisms. They help beginners by providing drawings explaining the most technical terms. If the key asks you whether a leaf's margins are "serrate" or "dentate," a drawing beside the question will show the difference. Though the series was first published several decades ago, it's being republished, plus used copies are worth looking for.

SPECIALIZED & TECHNICAL TERMS

Identification keys tend to use some rather specialized and technical terms/. For example, when you key out the common Black Oak from among 27 northeastern US oak species described in Gray's Manual of Botany, eighth edition, the following decisions must be made:

- Are stigmas sessile, or do the ovaries bear long, spreading styles?

- Are there 6 to 8 stamens, or 4 to 6?

- Are leaf lobes or teeth bristle-tipped, or entire?

- Are upper cup scales tightly appressed, or loosely imbricated?

- Are leaf bases cuneate to slightly rounded, or broadly rounded, subtruncate or rarely cuneate?

Stamens? Sessile stigmas as opposed to spreading styles? Cuneate or rounded or subtruncate leaf bases? Even when you think you understand all the words, as in "leaf lobes or teeth bristle-tipped, or entire," can you really visualize what's being talked about?

Unless you've taken botany classes or have taught yourself a lot, of course not. And the first time any aspiring naturalist decides to tackle keys, it's the same way with them.

LEAPFROGGING....

Happily, there's a way to dominate technical terms and concepts, and it's kind of fun doing so. It's called "leapfrogging," and here's how it works:

If you're on the Internet and you run into a term like dorsifixed, copy and paste the term into your browser's search window, type the word "define" before it and hit enter. Then you should have the definition right before your eyes. If you find such a term in a key in a book, most technical books have glossaries, so when you come to a term or concept you don't understand, simply look it up! Then look up the next term, and then the next, until it all comes together for you. At the right is part of our own glossary for terms applying to flower parts.

It's easy to plug any term into a search engine, plus there are online glossaries of biological terms, such as Wikipedia's Glossary of Biology