HURRICANE LILI

At 2:30 on Thursday morning Hurricane Lili announced her arrival much earlier than I had expected by sending rain through my mosquito net as I slept on the wooden platform. At 9 AM an FM station in Baton Rouge issued the current update. Winds had dropped to 100 mph as the eye crossed the Louisiana coastline. Lili's projected path was right up the Mississippi River, and Natchez and Vicksburg were specifically mentioned as in her path. She would reach here in mid-afternoon. The forecast ended by saying that winds were expected to be maintained 100 miles inland.

To me that said that in mid-afternoon we'd be seeing 100 mph winds here, and I knew that that would be disastrous. I stuffed my pockets with cornbread and pears and went rain-walking, for I wanted to view the proceedings.

To my astonishment, as the morning wore on, both rain and wind diminished. By mid-afternoon when the cataclysm was due it had stopped raining entirely and the winds were like simple spring breezes. I turned on the computer to work.

The moment the computer came to life I heard the sharp pops a big tree makes as it begins to fall. The pops came from the direction of the big Pecan overarching the trailer so I figured I'd better make a dash out the door. However, before I could undo myself from the rocking chair the poppings avalanched into a rampage of splitting and snapping. I bent over, hoping that if the trailer roof came down the bookshelves and table might slow it. I heard a growing whooshing sound and, most terrible, through the window I saw things getting dark fast, like the Hand of Doom descending over me. A tremendous bang rocked the trailer and I was amazed how long an instant could last as I ruminated on the fact that the next second in my life could easily determine how I lived the rest of my life, if I lived at all.

But that was it. I looked up and through the door's window I saw a general torrent of tattered leaves gracefully falling all around. It hadn't been the Pecan next to the trailer but rather the next one over, the one in which Mississippi Kites nested this summer, and only its topmost branches had hit the trailer.

The big tree absolutely flattened the dense thicket of 30-foot-high Sweetgums on the trailer's eastern side. Now each morning as I prepare breakfast, instead of gazing into a green, shadowy Sweetgum wall, I'll have a clear view to the next Pecan tree some 100 yards away. My closed-in, living-in-a-dense-forest feeling is gone. Now it's like occupying a recently logged forest, one in which some of the old trees still stand, now scarred and with waist-high splintered debris covering the ground all around. The balsamy odor of smashed Sweetgum still hangs strong in the air.

Last week I spoke of the living-in-an-opening-blossom feeling. Now that blossom is younger than before, is set back so that it has longer to go before reaching full bloom. There's nothing wrong with that, but I do mourn for the old tree, the home of the Mississippi Kites, of grand gardens of fern and Spanish moss on its massive, horizontal branches, of the thousands of insects and lizards and spiders that knew it as their entire universe.

*****

THE BEAUTY OF RAGWEED

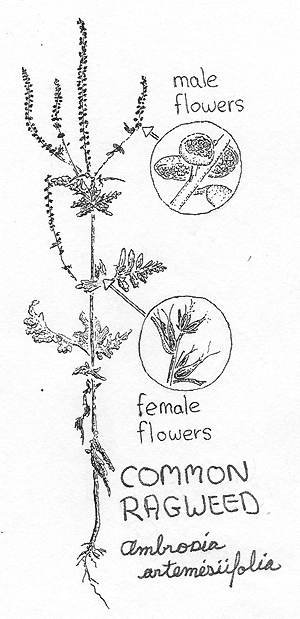

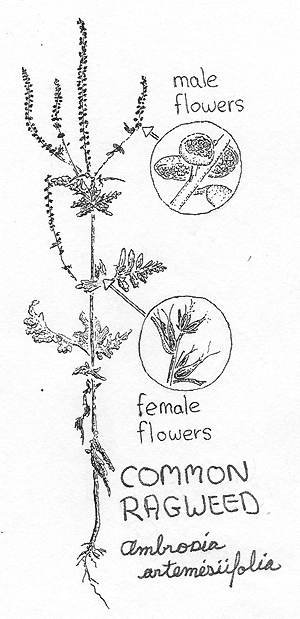

On Tuesday I had to bike to town to buy supplies. Seeing a favorite woodlot bulldozed into a gully, I focused on the beautifully symmetrical forms of ragweeds along the road, their exquisite flower structure (male flowers in pagodalike spires), and I thought about the role ragweeds play in plant succession, nursing the soil back to enough stability and integrity to support the community of living things that will succeed them.

Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful I whispered to myself eyeing the ragweed as I peddled past recently sawed-down trees, scalped and eroding soil, new gravel parking lots and newly junked cars, and more and more roadside trash as I approached town.

Two ragweed species are abundant and conspicuous along Lower Woodville Road:

Common Ragweed, Ambrosia artemisiifolia, bears dissected leaves a little like those of a garden carrot, and grows to about 7 feet tall.

Giant Ragweed, Ambrosia trifida, possesses broad, 3-lobed leaves and can get twice as large as the Common, though along the road usually it's not over 8 feet tall.

There are four or five ragweed species in our area, but these two are the common ones, and they are both native American species.

*****

SNORING OTTER

I emerged from a thicket of giant bamboo (an imported species) and took a seat as a River Otter noodled along the pond bank opposite me. In a minute or so he spotted me, but I didn't move so he wasn't sure what he was seeing. Surprisingly, now this otter began swimming toward me. In mid-pond he made a sharp blowing sound with his mouth, and that pfft! was instantly followed by a sound not unlike that of the sonorous snoring of a very fat man at peace, lasting for three seconds. As he swam toward me, two or three times he pfft!ed and snored, but when he got to within about 15 feet he suddenly dove. I followed his trail of bubbles with my binoculars so I was focused on him when he emerged in a different corner of the pond to repeat the behavior. He did this maybe eight times, always pfft!ing and snoring.

Then he swam into a dense thicket of overhanging Black Willow limbs where he snuggled next to his mate, who issued a high-pitched barking sound. They hid there about half an hour, then the first one returned to the pond and swam toward me pfft!ing and snoring again four times. Seeing that I was disturbing the couple, I melted back into the bamboo, thinking about what I'd seen.

I suspect that this was threatening behavior. Maybe he wanted to scare me away.

I have to admit that as he was coming toward me the first time the thought crossed my mind that he just might continue to the water's edge, slog up to my leg and begin chewing on it.

*****

FISH-EATING COTTONMOUTH

During my Thursday morning rain-walk waiting for Lili I returned to the pond where I'd seen this week's otters. This time no otters were observed but a large Cottonmouth swam about ten feet from shore. I see many Cottonmouths here but this one was doing something I've never seen before, and I'll bet that it was because it was raining. Maybe it's a behavior usually practiced only at night.

The snake would swim awhile, its head stiffly held from the water about eight inches high and at about a 75° angle, flicking its tongue in and out, sniffing the air. Then it would thrust its head below the water's surface to about the same depth it had held it into the air, and sway the submerged head back and forth as it swam forward. He gave every impression of looking for fish.

The Cottonmouth's Latin name is Agkistrodon piscivorus. That "piscivorus" means "fish-eater." My Audubon Reptile Field Guide says that Cottonmouths eat "sirens, frogs, fishes, snakes, and birds." I'm not sure about the sirens, but now it's easier to believe the fish part.

*****

EVENING GROSBEAK IN A TREETOP

On foggy, chilly Tuesday morning, just moments before a drenching rain began, a chunky songbird dropped from the sky and landed at the tiptop of the tallest tree in the area, a Black Oak between the forest and the Loblolly Field. I was walking there looking for fall migrants so when the visitor materialized from the mists exactly from the north, I felt sure I was seeing one. At the top of the tree the bird's spread-legged, jerky, looking-around body language indicated that he was really juiced up, on full alert, a true transient. In fact, just seconds after his landing the rain began and he took wing again, flying hard exactly southward, quickly vanishing into the morning's mist. It had been an Evening Grosbeak, easy to identify because of its very thick, white beak, yellow body and black wings, each wing with a large white spot.

I was surprised by this sighting because my field guides clearly show that Natchez lies far south of the species' southernmost winter distribution. Of course as soon as I got onto the Internet I Googled up a more up-to-date winter distribution map for the Evening Grosbeak. In contrast to my books, that map showed that in places this bird winters as far south as the Gulf Coast. My dog-eared field guides are decades old, and apparently the Evening Grosbeak's distribution has changed radically during recent years, probably because so many people put out feeders.

*****

ON THE GENTEEL ART OF PEEING SUSTAINABLY

During my recent bus trip to Kentucky the most vivid reminder that I had stepped from my usual life came when I had to pee. In the men's room of the Memphis Greyhound Station watching my pee drain through the hole at the bottom of the urinal, I was swept with a sense of squandering a profoundly important resource.

For, in my usual life I recycle the nutrients that pass through my body. For a long time I have known the value of human urine. For instance, on the Web I've read that each person's waste fluids can provide enough nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium to grow a year's supply of wheat and maize for that person. Urine can be applied to field crops without treatment because it is generally sterile. Fresh urine contains no bacteria unless the person has a urinary tract infection.

Despite my being a urine disciple, for a long time I've hesitated to discuss this in the Newsletter, for I know how squeamish people in our culture are about these things. However, now the time has come, for these reasons:

# I have developed and tested a workable system for dealing with my own urine.

# Our society must face its refuse-disposal problem.

# Recycling our personal wastes is a beautiful, life-confirming process that should be celebrated, not shunned

I have set up two simple and effective peeing systems, one for myself and another for visitors. Visitors pee in a five-gallon bucket, the bottom of which is covered with sawdust, and the top of which is equipped with a regular commode seat. When sawdust in the bucket is peed into, fresh sawdust from a companion bucket is spread over it. When the pee bucket fills, the contents are dumped onto the compost heap and a layer of organic material, usually straw, is strewn over that. As long as fresh sawdust and fresh straw are used effectively, little odor results in either the bucket or the compost heap.

The second system, which I use, is this: I pee directly onto the compost heap. I start out with a layer of straw, or whatever organic material may be at hand, and when the layer darkens and begins to smell, I cover it with a fresh layer of organic material. Pee-saturated straw composts wonderfully. When straw that has composted two or three months is dug out, it is black, crumbly, and pleasantly earthy-smelling.

I don't mean to imply that these systems stay sweet-smelling all the time. Sometimes when the top is lifted from the five-gallon bucket the odor is powerful. This is a sign that more sawdust should have been added the last time, or that the bucket needs to be emptied. Similarly, in the middle of a calm, hot day when sun shines on the compost heap, if you put your face right over it and breathe deeply, it might curl your toes.

However, I judge these mild affronts to our senses as appropriate trade-offs for being able to avoid the waste and pollution typical of our society's approach. Also, this occasional smell of ammonia reminds us of our real position in the ever-recycling, self-sustaining Web of Life, which has value in itself. Finally, I end up with some really great compost.

The logical next question is, "Where does my manure go?" I'll address that in next week's Newsletter.

*****

BROWN THRASHERS IN A WAVE

Fall migration of birds is going on right now, and it's very different from spring migration. This spring, migrants wore bright spring plumage and they sang with abandon. Now they are mostly somber-colored, usually quiet or silent, and mostly make an effort to pass unseen. It would be easy not to notice the passage, but each day there are certain hints of what's going on. Hoeing in the garden I hear a single chip-sound from a Rose-breasted Grosbeak. Deep in the night from high in the black sky I hear a single lonely skronk from some kind of crane or large heron. A brief cheep in the bushes pinpoints an American Redstart snapping gnats among the shadows.

Often waves of migrants arrive on weather fronts. This Tuesday, I think it was, a cold front (into the 60s) just reached us and stalled out, and it brought with it a hilarious number of Brown Thrashers. We have Brown Thrashers year round, so these new ones hailed from farther north. During the winter in the Mississippi Valley Brown Thrashers are found no farther north than southern Kentucky, approximately.

I took a walk on the day the big wave of Brown Thrashers came in. With the cold front stalled atop us, it was drizzly and chilly -- somber. But there were so many Brown Thrashers I had to laugh. It seemed every big tree, every fencerow, every brushpile, every blackberry bramble had its Brown Thrasher, and they weren't silent, either. Brown Thrashers, being in the same family as Mockingbirds and Catbirds, are brilliant singers, but now in this broody chill they issued a growly churrrr call, the warning many birds make to announce a snake in the vicinity. Sometimes they also issued a liquid smacking sound. Nothing of music here, just these strange, almost unsettling calls emanating from every shadow and every form on the landscape.

Because Brown Thrashers prefer semi-open areas instead of thick forest, I've seldom seen them around my camp. However, now that Hurricane Lili brought down the big Pecan that flattened all those 30-ft-tall Sweetgums next to my trailer, the heap of snapped twigs, splintered limbs and tattered leaves seems to be of the birds' liking, and some have been hanging around my camp.

Making up for that day's melancholy churrrrs and liquid smackings, on Thursday afternoon the sun came out brilliantly and as I sat working at my computer a Brown Thrasher hopped past just outside my door. How vibrant and warm his rusty-colored back was in the sunshine, and how striking were his piercing, yellow-orange eyes. He was a proud-looking, self-assured bird, and for a moment I think he paused and cocked his head to listen to the Bach fugues filtering through my screen door.

Who would have thought that such a pleasing moment might blossom from the hurricane-inspired demise of an old Pecan tree?

*****

GEESE JUST BEFORE DAWN

Friday morning, about an hour before the first hint of dawn, I heard a large number of Canada Geese flying overhead. The wild members of this species spend their summers in Canada and the US Northwest, and overwinter in the southern US and farther north along the coasts. Their overwintering habits have changed during recent history because so many manmade lakes have been built, and people feed them through the winter. All winter I'll hear and see them here, for St. Catherine Creek National Wildlife Refuge, on ground once belonging to this plantation, now occupies the land between the plantation and the Mississippi River, and that refuge is a wonderland of swamps, streams and flooded fields -- prime habitat for Canada Geese.

Lying snugly within my Kentucky quilts, Friday just before dawn I tried to detect what emotional state the geese were expressing in their calls, though I'm not sure at all that a human can do that. I could certainly imagine how beautiful it must be to be a goose flying high inside a great V in the black sky, the fellow members of my family/flock/tribe sailing with me, the silvery Mississippi slowly gliding by below on my right, the air around me slowly growing balmy and friendly after flying for so long in the biting chill behind the cold front that at that time lay just to the north of us.

However, it seemed to me that what I heard in their voices was anxiety, a certain nervousness. It was very dark, with clouds masking the moon and, really, it's hard to imagine that they could even see the Mississippi. Being so high and needing to land, but not being able to see much of what lay below...

*****

HOT WATER & CHINESE

The next morning, Saturday, at the same time as on Friday morning, I was awakened by a nearby flash of lightening and subsequent bone-jarring thunder. Maybe the arrival of the geese a day before the cold-front was no coincidence. All day Saturday it stormed and rained here, dumping over three inches of rain on us, atop the inch of rain the day before. Once I'd managed to prepare my campfire breakfast during the deluge, I found the storm much to my liking. For, it provided an unexpected quiet period for me.

Most people seem to think that here in my little camp I must spend a lot of time "hanging loose," just goofing off. In reality, each day I spend mornings working in the gardens and nearly all the rest of the time developing my Internet projects. I suspect that my days are at least as structured and intense as are the days of those of you with regular jobs.

So, Saturday morning I couldn't garden and there was too much lightening to have my computer on. Therefore I did what I often do in such enforced rest periods: I fixed a big mug of hot water, and studied Chinese.

People in our culture underestimate the pleasure in drinking simple hot water, especially steamy, pure rainwater. During my recent travels I as struck by how often people around me habitually sipped liquids -- coffee, sodas, Strawberry-Kiwi herbal tea, beer, whatever. To my mind, these people focused so exclusively on titillating their taste buds that they overlooked the more fundamental pleasure of simply refreshing the body with pure water.

Tickling taste buds and gratifying the body with exactly what it needs are unequal pleasures. The one, though certainly having its place, is superficial, fleeting, and often damaging to the body or even addictive. The other is a natural and necessary maintenance, and when the water is hot on a chilly, stormy day its drinking satisfies in a deeply, perhaps atavistic, manner. Drinking hot water on such days has calmed the spirits of a million generations of our ancestors in their caves and dark lodges. Drinking hot water can be a kind of communion with them, and with the spirit of simple survival in a hostile world.

I also find studying Chinese to be a deeply satisfying experience. I am afraid that people nowadays have forgotten that learning, by itself, can be gratifying.

As rain tapped on my roof and I drank steaming hot water from my mug in this drenched little corner of the forest I wandered into the psychology of Chinese people as manifested in their written language. The Chinese character for "good" consists of the symbol for "woman" next to the symbol for "child." How can you but be impressed by a culture that expresses itself in such a simple but profound manner? And what pleasure it is for the mind to be reminded on such a morning as Saturday's that the Chinese character for "fragrant" is nothing less than the symbol for "grain," such as wheat, set with the symbol for "sun."

Thus -- the sun warming a field of wheat produces a fragrance. The glow caused by these insights harmonizes beautifully with the glow brought by steaming water on a rainy morning.

*****

DAYS OF PERFECTION

Let it be known that I am not one to become so absorbed in nature's intricacies and minutia that I ignore the broad, simple glories of perfect days arriving unannounced and unexpected. If I'm engrossed in the wing venation of a wasp or the exact nature of a leaf's margin, and it's an afternoon golden and balmy served up like a sweet apple on a silver platter, I will reach for that apple.

The nights this week have been glorious. A bright, waning moon and temperatures at dawn as low as 48° made for cozy, profound sleeping. Awakening as the first light glowed in the east, sharp coldness sent me springing from the sleeping platform right into my jogging shoes, and within moments I was running through ghostly fog, water droplets coalescing in my beard. Every day this week friendly breakfast fires provided mugs of steaming mint tea, and my skillet-size cucumber "omelets" made with fresh dill and jalapeños always baked to a handsome brownness. I'd work in the garden as the sun burned off the fog, and then on the Internet I'd find my tasks pleasing and fulfilling. Sometimes I'd just wander around checking on seedlings, seeing whether the cuttings were taking root, and making sure the potted plants were healthy. Balmy, late afternoons were occupied with odd jobs and listening to All Things Considered on Public Radio, and then as the chill grew moment by moment I'd read into the night as the crickets grew ever more silent.

I am grateful for it all, grateful to be at a peak of sensitivity, grateful to be healthy, and to have discovered how hard manual labor mingled with creative thinking and freely given service to the broader community produce in me something like happiness. I am so grateful for everything that when I pray I never pray asking for favors, only to give thanks to the Great Unknown.

Golden days, golden days...

*****

MEADOW MUSHROOM IN A GRASSY ROAD

It being fall and a few showers having come our way, mushrooms are popping up everywhere. I can't identify a lot of them, but this week a cluster of one species materialized between the tracks of the grassy road leading to the barn, and I recognized that species at first glance. When I lived just outside the little Waloonian town of Nivelles south of Brussels, Belgium, during two summers, I frequently visited a certain nearby pasture where sometimes I could gather half a bushel of this species, or more. Here we call it the Meadow Mushroom, Agaricus campestris. In French it was Rosé des Prés.

It has a bland taste and is thus perfect for slicing raw into salads, and for soaking up herbal flavors in sautéed dishes. Another good thing about it is that it's easy to identify. It's a white mushroom with pink gills that turn brown as the mushroom matures. The stem has a ring around it. The mushroom's white cap and stem ring cause it to be similar to some of the deadly Amanitas. However, Amanitas produce white spores while this Agaricus has dark brown ones, and not many mushrooms have dark brown spores.

Spore color is one of the most important field characteristics to pay attention to when identifying mushrooms. Mushroom spore colors range from white to black, through yellowish and gray and a host of brown hues, from cinnamon-brown and purple-brown to dark chocolate brown.

If you've never made a spore print, you should, just for the fun of it. Place the cap of a mushroom in its early stages of maturity on a piece of paper and after a few hours you'll get a pretty star-burst pattern on the paper, consisting of spores released from the cap's gills. Just hope the spores don't turn out to be the same color as your paper.

*****

RECYCLING MY OWN HUMANURE

At some point, the person wanting to reduce his or her own impact on the environment, and to live in a manner respecting the true value of things, has to confront this fact: Our own feces creates a real mess if handled wrongly, but has great value if handled rightly.

Our society's usual manner of handling it completely ignores its value, and flirts with its dangerousness. How many beaches are closed, how many miles of rivers are off limits to fishing, and how many tons of chlorine are dumped into our drinking water because of "fecal coliform bacteria" -- bacteria originating in the intestines of warm-blooded animals?

Last week I made the point that unless a person has a urinary tract disease, human urine is so sterile that it can be used to wash out wounds. In fact, Newsletter subscriber Leona Heitsch in Missouri wrote recalling that her mother once told her that "...when she was a kid, they used the contents of the chamber pot to balm their hands after picking up potatoes in the raw Michigan cold... it neutralized the effect of the cold earth on their hands and relieved dryness and cracking."

In contrast to urine's sterility, average human feces consists of about 25% bacteria, sometimes much more. If that bacteria contaminates human food, serious illness, sometimes even death, can occur.

Therefore, I've long felt ambivalent about what to do with my own manure. On the one hand I have read how important the use of human manure is in Asian agriculture, and I have seen some of these practices myself in India. On the other hand, my mother was as neat and clean as they come, and she passed on her concepts to me the way any good mother does. My default attitude toward my own feces has been until now "flush and forget."

But, here, now, I don't allow myself the luxury of not examining the consequences -- the ethics -- of everything I do, and everything I think.

One catalyst for my deciding to confront the question of what to do with my own feces came when I read The Humanure Handbook, A Guide to Composting Human Manure by J.C. Jenkins.

In this book we read that human manure, or humanure, by wet weight is 5-7% nitrogen, 3.5-4% phosphorus, 1- 2.5% potassium and 4-5% calcium. These are nutrients that living things need and they should not be flushed from local ecosystems.

For me the most striking part of the humanure book is a chart showing how much heat and time are needed to kill disease-causing bacteria. If you heat something at 113°F for one week, not only disease-causing bacteria but also dangerous viruses, roundworms, amoebas and other such organisms will die. The same can be accomplished if you heat it at 145°F for one hour. For my situation, these were the most important figures: You'll kill disease-causing organisms if your compost heap maintains a temperature of 122° F for just one day.

I have seen that my own heaps, when I do a good job building them and pay attention especially to the carbon/nitrogen ratio, cook along at about 140°F for several days before starting to cool off slowly. In other words, if I should compost my own manure, the resulting compost should be free of disease-causing organisms.

A "Porta Potti Continental," a kind of portable toilet, came with my little trailer. Basically it's a regular commode seat fixed atop a large, plastic container. When the container is full, the seat easily detaches and the container can be carried by its handle to where its contents can be poured out. I pour the contents onto my compost heap.

Immediately upon dumping the Porta Potti's contents onto my heap, I scatter some already-prepared compost atop it, to "seed" it with composting bacteria. Then I spread about six inches of fresh straw or other organic material over that, effectively sealing the odor inside. During following days I pee atop the fresh straw, as described last week. In a couple of weeks the straw becomes saturated and it becomes time to dump the Porta Potti contents again. The Humanure book advises to not occasionally stir up the straw to aerate it. Just let it sit there and cook as long as it wants, and when the bin gets full (after about a year at my rate), then start another bin. A few weeks after finishing the first bin, you can begin gardening with the compost.

This systems works beautifully for me, but I'm not sure if it's transferable to other people. For one thing, I know that what comes out of vegetarian me has much less smell than that from others who eat animal flesh. Similarly, my diet is high in fiber, so what comes from me is much looser than what comes from people eating processed food. Each person needs to experiment with his or her local conditions.

It's all quite simple. And, when you think about it -- about taking control of this aspect of your life and making something good out of a waste -- it's even quite beautiful. No chemicals, no pollutants, no taxes, no costs at all, in fact ending up for free with a fine compost that makes flowers blossom, and vegetables grow like crazy.

*****

ASTERS

It's fall, so asters are blossoming. One nice thing about asters is that at first glance they all look the same, but once you start examining them systematically you realize that there's a whole aster world worth knowing. On my recent backpacking trip on the Appalachian Trail I counted over a dozen species before I lost track, and most species were fairly restricted to a certain elevation, a certain geology, or a certain spot on the dry/sunny to wet/shaded scale.

Arthur Cronquist's Vascular Flora of the Southeastern United States lists 66 aster species for the region covered, and many of those species are further subdivided into varieties. An aster species has even managed to invade my garden. It's the White Heath Aster, Aster pilosus, possibly the most common aster of all, since it lives along roadsides and other disturbed sites. In other words, it's a "weed." Nonetheless it's a "classic aster" bearing a large spray of small blossoms composed of white rays and yellow centers. Like most weeds, it's found over a large area -- from Maine and Wisconsin to Florida and Louisiana.

Next to a post of my outdoor kitchen there's a less-weedy species whose rays are pale lilac and whose lower leaves are heart-shaped, on a long petiole. This is the Drummond's Aster, Aster drummondii, usually occurring in clearings and open woods, and distributed from southern Ohio and Minnesota south to Mississippi and Texas.

I've always enjoyed "variations on a theme." I love Bach fugues, which take a melody, then repeat it with minor variations, and finally transform that melody into statements almost sounding like something completely new. That's the way asters are.

There's a "classic aster" concept, but then there are many variations on this classic-aster theme. In the musical genre we know as "flowering plants" there once long ago appeared a melody known as "the first aster." Then through the beautiful process of evolution all these "variations on the aster theme" came to populate our lives today.

Because evolution is such an all-pervasive phenomenon throughout all of nature, again and again, at all levels of perception and understanding, the naturalist discovers occasions of "variations on a theme" being robustly generated, and perhaps nothing is quite as life-affirming as this.

*****

CARPENTER BEES

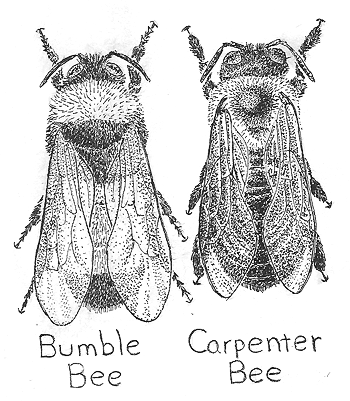

Earlier I told you how Carpenter Bees were tearing open the sides of certain blossoms in order to "rob" the flowers of their pollen without pollinating them the usual way. Thanks to some recent cold mornings I've learned more about this bee.

My little trailer is unheated so during winters I build a box around my computer and on cold nights keep a small light burning in the box to keep the computer warm. Wednesday morning's 38° surprised me so when I turned on my computer I got a blank screen -- something inside the computer was too cold to work. So I set about constructing this winter's box. For my frame I found some discarded two-by-fours that were riddled with holes excavated by Carpenter Bees. The holes were barely large enough to admit the tip of my smallest fingers. While sawing these boards I happened to cut through a Carpenter-Bee hole.

The hole went down about an inch deep and then formed a kind of T, with each arm of the T traveling in opposite directions inside the board. At the end of each tunnel there were two Carpenter Bees, four in total, all buzzing their discontent with my sawing. I was sorry to mess up such a cozy overwintering nest; I'd thought the holes were abandoned.

Anyway, one of the T's arms was five inches long and the other was seven. Certainly a bee capable of gnawing away so much wood can with ease rip open the side of a tubular flower!

*****

AUNT BELLE

I dedicate this Newsletter to my Aunt Belle, who this week died of Parkinson's Disease in my home community of Semiway, a tiny place with undefined borders in rural western Kentucky. Aunt Belle died in her own home, surrounded by family, and she died with dignity.

Old country people like Aunt Belle are the guardians of a powerful insight into life. That insight is that when you live simply, nature (insert "God" if you wish) provides. Now there is one less human on Earth sharing that wisdom with us, and we are the poorer for it.

Aunt Belle lived from one year's gardening to the next. Winter for her was a hopeful time for scanning seed catalogs and for pointing out to visitors how nicely her Christmas Cactus's crimson blossoms glowed in the sunlight filtering through her little trailer's windows. Those of you who know me personally probably recognize a certain resonance between her life and the life to which I aspire. This is no coincidence.

As a child I saw around me many manners of being. Some people delighted in big cars and houses, others just did their work-a-day jobs and left it at that, some liked booze, some dreamed of Las Vegas and hitting it rich, and some were never pleased with anything. Aunt Belle delighted in how well her potatoes came up and how pretty her geraniums were even if they grew in rusty old lard cans. And she always had fresh cornbread fixed when I went to visit.

Today I am looking for a lard can, and a geranium to plant in it. For, the lives of Aunt Belle and other good folk like her have suggested to me a path toward contentment, and a higher level of spirituality, that nowadays I follow and do not intend to abandon.

Thanks, Aunt Belle.

*****

DANCING MUSHROOM ON A FROSTY MORNING

After a week of sunny days with afternoon temperatures usually in the 80s this Sunday morning at dawn the temperature inside my camp's Waxmyrtle tree was 32° and the fields and pastures were spotted with the season's first frost. The big Pecan trees above my trailer are 95% leafless now, though the young Sweetgums surrounding me remain as green as in July. During these days everything presents itself in high contrast, like black shadows that pool wherever the dazzling sunlight can't directly hit.

Breakfast this morning was particularly vivid, everything about it scintillating, cutting, brilliant, immediate – not only the feeling of the scorching, orange campfire-blazes flickering next to me as the air tingled and numbed me with coldness, but also the food itself. Today's breakfast became approximately the fifth-most-tasty meal of my life.

Breakfast was so good mainly because nowadays there's a certain wonderful mushroom appearing at the bases of occasional old oak trees around here. This fungus has many, many names because it is distributed over much of the world (mushroom spores can take transcontinental trips on the wind). I think local people here may call it Hen of the Woods, but its most common name internationally is Maitake, a Japanese name, I think. In German it's Klapperschwamm, but the name I like most is one I found on the Internet, and that's Dancing Mushroom, a name perfect for a steam-and-smoke-swirling-in-sunlight morning like this one. In Latin the mushroom's name is Grifola frondosa.

The fungus body, the size of a basketball and larger, consists of many densely clustered, smaller, ear-shaped mushrooms, sort of looking like a giant pine cone. I don't think its taste is particularly exciting but it has the texture of soft chicken breast, and when I sauté it in olive oil with garlic, green onion, and jalapeño and bell peppers, scramble in a couple of eggs and sprinkle on fresh basil and a bit of fresh rosemary (everything except the olive oil and eggs from my gardens or the woods), the taste is as explosive as steam from my breath this morning after a big swig of hot water, breathing into the frigid air. I will never forget this morning's perfect breakfast with the Dancing Mushroom.

*****

NODDING LADIES'-TRESSES

Uncommon but not rare throughout the forest around my trailer nowadays there's a wild orchid flowering, called Nodding Ladies'-tresses, Spiranthes cernua. It's such a small plant with such an inconspicuous, slender spike of tiny white flowers that most people would overlook it and few who notice it would dream that it could be an orchid. However, if you look at the 3/8-inch-long blossoms under magnification you'll see that structurally they are unmistakably similar to any gaudy corsage-orchid. In Mississippi, Nodding Ladies'-tresses blossoms from July through November.

You might be surprised to learn that of all the families of flowering plants --such as the Oak Family, the Rose Family, the Bean Family -- the Orchid family has the greatest number of species of all -- some 25,000-35,000! The vast majority of them are tropical, however.

*****

WHAT THE ORCHIDS TEACH

My Ladies'-tresses got me to thinking about how the Orchid Family's fabulous success in producing so many species provides insights into nature's general tendencies. For me, recognizing "nature's general tendencies" is a bit like someone else in our culture searching in the Bible or some other holy book in the hope of understanding "what God's plan is." Here is at least part of what the Orchid Family teaches me:

First of all I recognize that the evolution of living things proceeds more or less like a tree that starts as a single sprout, branches, and then the branches rebranch, and so forth, with the branches growing and rebranching at different speeds and with different degrees of vigor. Earth's first large, land-based plants reproduced with spores, and they appeared over 400 million years ago. Flowering plants did not come onto the scene until much less than a hundred million years ago, thus they are situated about 4/5 of the way up the evolutionary tree. And then orchids did not appear among the flowering plants until relatively recently, geologically speaking, so they occupy only an outermost twig of the vast evolutionary tree. Thus one thing orchids teach is that newcomers sometimes have ideas exactly right for their time; you shouldn't always depend on "the establishment" to get things right.

What are some of the new-fangled ideas orchids display? For one thing, orchid flowers fuse "traditional" flower parts (calyx, corolla, stamens, etc.) into very specialized structures favoring an efficient pollination system no longer relying on powdery pollen. Also, despite the impression given by flower-shop orchids, most orchid flowers, such as my Ladies'-tresses, are much smaller than flowers of "more primitive" species. Another thing is that orchid species generally occupy very narrow ecological niches -- they are much more fussy about where they live than the average plant. Finally, orchid seeds are so small that a single pod may contain thousands of seeds, yet if just one of those seeds manages to germinate and grow into a mature plant the orchid is lucky.

If you think about it, the recent evolution of computers has followed the same path as that taken by orchids:

# Both computers and orchids have evolved toward ever higher efficiency, miniaturization, and specialization.

# As computer networks expand, and orchid ecology becomes more intricate, the value of the individual computer/orchid diminishes as the computer-network/ecosystem consolidates, expands, and grows more sophisticated.

A good topic for a long night's discussion would be how human history and today's evolving human societies manifest these very same trends, and what that means to us today.

The orchids also show that nature doesn't put all Her eggs into one basket. In the forest around us the Magnolia Family is considered to be one of the most primitive among flowering-plant families, yet here the magnolias appear to be thriving quite as well as orchids.

I personally find this last observation tremendously encouraging, for it reminds us that Nature loves diversity. In a world where orchids and Silicon-Valley yuppies appear to be poised to inherit the Earth, plodding magnolias still can offer their perfume, and simple hermits smelling of woodsmoke can live in dignity.