BIRDSONG SEQUENCE AT DAWN

Most of the year I sleep in the forest on a wooden platform built high enough to keep ticks from climbing the legs, and covered with mosquito netting. Nowadays at dusk the loudness of the high whine the mosquitoes make trying to get at me is almost intimidating. Yet, it's rather cozy inside the net, completely mosquito free. The trick is to sleep there all night without poking the butt against the netting.

Awakening there in the cool of the morning is wonderful. With just a hint of light toward the east, the Cardinals begin singing. Several call from scattered locations all around, proclaiming their nesting territories. After they've called awhile and the darkness has lifted more, then the Summer Tanagers join. Then the Indigo Buntings, then the Yellow-breasted Chats, and by the time the Towhees are calling I know it's light enough to get up and go jogging. During my stretching exercises, the next species to sing is the White-eyed Vireo, then the Crow, and when the Carolina Wrens join in I know that if I'm not on the road jogging I'm behind schedule. Sometimes the sequence of species is different, but this is the usual one. Especially if it's cloudy the sequence can change a little.

One omission in the above list is the American Robin, which in most American suburbs may be the most common bird. For several weeks this spring I did a birdcount of migratory species for the Gulf Coast Bird Observatory and during all of spring until now I have not seen a single American Robin. I don't know why this is so. This is one of those little mysteries I'm working on. .

*****

ME AND THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

I love this kind of weather. For weeks it's been so humid that morning haze and afternoon cloudiness have kept it cooler than if the sun had shined all the time, and if it does get very hot then you can bet that a storm will soon come up cooling things off. On the Internet, if you watch the regional radar in the afternoons you'll see storms popping up all over like mushrooms. They're quick and violent, and then they're gone, and mostly they miss you. Hearing the thunder through the afternoons as the storms come and go is very satisfying. I'm getting deaf. Birdcalls and cricket sounds are drifting away from me, but I can hear that thunder all through my body.

Sometimes I take up my hoe or scythe and go work in mid afternoon heat, exactly when, because of the heat, it's hardest to breathe and keep going. But I like feeling all that weather-power around me, experiencing my body sweating and tingling with edgy just-surviving. When a little breeze comes along, the coolness rippling across my back and legs is one of the purist, most uncomplicated pleasures a human can enjoy. The other day I heard a Johnny Cash ballad in which he sang something like "I hurt myself just to see if I could still feel." That's not me, but Johnny and I are exploring similar corners of the human condition.

When I'm working and there's a storm brewing nearby, and from the corner of my eye I'm watching flashes in the slaty darkness to my side, sometimes I feel like I'm on a powerfully dramatic stage. Maybe I'm just a tall, balding hermit dressed less elegantly than some would like, but when I'm out there with the looming storm it's like being in the old classic movie Dr. Zhivago. For, maybe my dedication to sustainable living in a small way can be compared to the sacrifices of those nearly a century ago who worked and died for the Russian Revolution. The great storm rearing next to me is the Revolution itself with its flashing cannons and mindless destruction, and the heat and humidity in which the scene is cast accomplish the same poetic resonance as the cold and snow did for Dr. Zhivago.

How beautiful to work beneath a sky that's so heavy, dense and potentially dangerous, while silently within I'm harboring this unshakable dedication to something grander, as the great revolution comes, comes, comes...

****

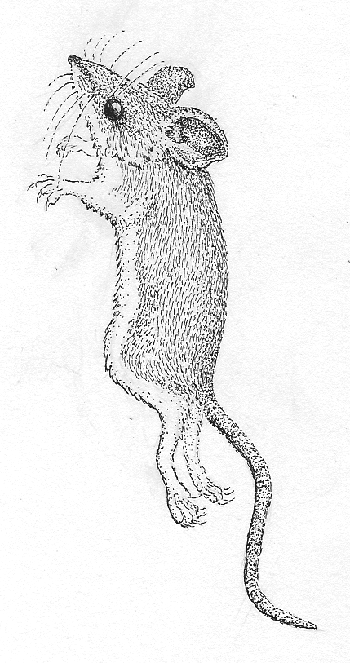

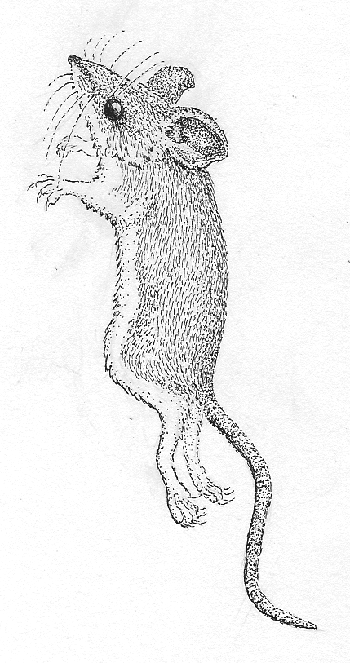

WHITE-FOOTED MOUSE

It's too bad that when most people think of mice they visualize a House Mouse. The House Mouse is just one mouse species among many, plus it's an introduced species from Europe. Really, it is a "weed species" among a rainbow of wonderful native rodents.

I'm thinking about mice now because for the last couple of weeks my trailer has hosted the most recent of a long series of White-footed Mice, and this one I have not been able to trap. Of course I didn't want to hurt him or her so I tried all my usual live-trapping methods. But this was a smart mouse and simply refused to enter the various one-way doors and snares I contrived. Twice I cornered the critter and both times as I was driving him toward the open door in a flash he turned toward me and either ran between my legs or jumped onto me, then onto the floor behind me.

Finally this week as I worked at the computer I heard the little intruder inside the toolbox beneath my sleeping platform. I sneaked over, closed the box, took the box outside, opened it, and there was my guest looking with its enormous eyes right into my eyes -- for about half a second, before it turned, leaped a good four feet onto my elevated fireplace, and disappeared.

White-footed Mice are amazing jumpers -- can jump right out of a large bucket. Also they are handsomely rusty-gray above and white below, with huge eyes and ears -- very unlike the squinty-eyed, gray House Mouse.

White-footed Mice are abundant here, in every brushpile, every outhouse, all through the woods and fields. The species is native over a vast region of the eastern and central US, deep into Mexico. It eats mainly seeds, nuts and insects, and each individual has a home range of from a half to 1.5 acres, with 4-12 individuals occurring per acre.

The unfortunate thing is that they also carry ticks infected with Lyme Disease, and we live in a hot-spot for that. Both the plantation manager and myself contracted Lyme Disease a couple of springs ago when ticks were especially bad.

****

FIG PICKING

This week figs began ripening at full speed. There were a few last week, but this week each morning when I crossed the bayou the first hour or so was spent just picking figs.

It's not a bad way to start a day's work. I see a plump, purplish fig, place its stem between two of my fingers, give a tug of a certain strength, and if the fig is properly ripe it breaks off. That "tug of a certain strength" is something you have to learn; no book can teach it. I am always tickled to know something a book can't teach.

It's too hot to wear more than a pair of shorts and a sweatband so the trees' rough leaves scratch against my body and the brittle limbs poke at me. After a while I get good and sweaty and itchy, and my hands are all gummy from the figs' latex. This is "deep immersion" and in a strange way it feels good. When I'm inside the trees with morning sunlight slanting in from the east, I feel like a goldfish in a brightly lit little aquarium thick with seaweed. And the sweat and itching make the stretched-for fig a little sweeter.

*****

BLUEGILL NESTING

In the woods I sat quietly next to a deer pond about the size of a house. It was a shallow pond with fallen limbs emerging all across it and its waters were murky brown in the center, turning rusty red at the edges. With all the frogs and dragonflies there was plenty to watch, but my attention was focused on some shallow depressions at the pond's edge.

The depression rims were about six inches below the water's surface and the bottoms of the depressions were about twice as deep. The holes themselves were about 20 inches across and some five feet from one another. Each depression was clearly a nest, for it was being attended very conscientiously by an adult Bluegill fish, Lepomis macrochirus, about six inches long.

Male Bluegills excavate nests by undulating their rear ends from side to side while remaining in a vertical position. The males then wait in their nests making grunting sounds to attract females. Once a female enters a nest and after the pair swim in circles awhile the female releases a few eggs and the male releases his milt. Then it's all done again. The female doesn't deposit all of her eggs during one visit, nor is only one nest used by a female. Once spawning is completed, the female leaves the nest and the male remains caring for the eggs. What I was seeing in this pond was males tending their nests.

I think they must have been under a lot of stress that day. It was around 90° and in that shallow water the oxygen level must have been low. In fact, the males would vigorously swim in circles for about 15 seconds, then come to the water's surface over their depressions' centers and seem to gasp for air for up to a minute before swimming in circles again. The circle-swimming was surely to aerate the eggs.

The pond also was thick with Mosquitofish and every few minutes a school of these would slowly approach a nest. As soon as the father Bluegill spotted them he'd chase them away. In the mid-day heat these Bluegill fathers seemed pretty fagged out, but they just kept at it.

*****

MELLOW MODULATION

Walking in the fields and woods now feels completely different from just two or three weeks ago. Earlier there was a sense of outward-rushing blossoming wherever I looked, but now the feeling is more introspective, more mellow. Of course the catalyst is that now instead of the days getting longer, they're getting shorter.

The same kind of mood-shifting happens in music. The term "modulation" refers to the changing of musical keys, especially without breaking the melody. One moment the music sounds bright and simple, the next suddenly it's dark and foreboding, yet the tempo may remain the same, and the music may be neither louder nor softer -- just that the key has changed. The Key of C usually sounds cheerful and uncomplicated but the Key of E-flat Minor typically sounds dark, serious and pensive. Andrew Lloyd Webber really jerks our emotions around with his in-your-face modulations in "The Phantom of the Opera."

Maybe we humans are so vulnerable to musical modulations because we evolved to intensely feel modulations in the seasons around us. Our ancestors' nervous systems must have developed exquisite sensitivities to variations in sunrises and sunsets, to how the earth's odor changed depending on its content of moisture and organic matter, etc.

If the Earth and all of Creation is the Creator's music, and the Universe's discrete things are analogous to tones in human music, then why shouldn't the profoundly significant modulations of the Earth's seasons delight and fulfill us in ways mere music never can?

***

HOMOSEXUALITY IN NATURE

The other day one of my favorite local folks dropped by to share some of his delicious blueberries, and to chat for a bit. This time his remark that got me going was that I knew how progressive he was on matters, but when it came to gay marriages, he just couldn't take it, and surely nature doesn't put up with things such as that.

I couldn't ignore my friend's assertion that nature doesn't put up with such things as homosexuality.

For, nothing is more experimental and broad-minded than Mother Nature. When you look at the Creation you clearly see that the Creator's plan is to create diversity at all levels of reality, and to evolve that diversity to ever higher levels of sophistication -- whether it's forming galaxies from hydrogen gas, or evolving life on Earth. Moreover, just about any strategy furthering those blossomings is acceptable.

Among plants, sometimes a species' flowers possess both male and female sex organs. In other species, individual plants may bear only one gender of unisexual flowers, while in other species individual bear both all male and and all female flowers. Sometimes flowers are designed so they can't self-pollinate, other times they have to pollinate themselves, and some plants skip the sex scene altogether by reproducing vegetatively.

Among animals we find everything from the male seahorse who carries the eggs, hatches them and takes care of the young, to the "polyandrous" Spotted Sandpiper whose females may lay up to four nests in a season, each equipped with a different male incubating the eggs. Of course the common earthworm is both male and female, and some snails sometimes mate with themselves, producing offspring. On the Internet you can find academic papers detailing homosexual behaviors in a wide variety of primates, from langurs to orangutans to pit-tailed macaques.

The higher up the evolutionary scale you go, the kinkier it all gets. Among communities of mice and other mammals, when population density reaches a certain high level where diseases and famine threaten, not only does homosexual behavior appear but also parents begin killing their own offspring. It's always the case that the Creator chooses the welfare of the species or community over that of the individual.

Among human populations, homosexuality occurs at a certain rate in all populations.

Thus, homosexuality is natural and inevitable. Data suggest that homosexuality may be at least partly genetically determined.

In short, it's simply wrong to say that homosexual behavior is never natural.

Why would the Creator create this state of affairs among humans? I don't know, but my own experience with human gays is that, on the average, they are more sensitive, insightful, creative, caring and smarter than the rest of us, so maybe that's enough of an answer right there.

With regard to the morality of it all, I would say that at this time when so many young people desperately need love and care, and so many gay couples want to provide stable family structures by providing that love and care, institutionalizing laws to prevent gay couples from enjoying the kind of legal and social support non-gay families already have, is immoral.

Moreover, since the Creator has made it so that among higher mammals homosexual behavior increases in populations under stress, and humanity right now, because of overpopulation and inequitable distribution of resources, is under enormous stress, the phenomenon of gays suddenly stepping forth to demand their right to establish stable family units while not themselves contributing to even greater overpopulation, can be seen not only as natural but also, literally, a godsend.

*****

WASPS CARRYING SPIDERS

These days it's not unusual to see a wasp lugging through the air something nearly as large as its own body. Sometimes the wasp even drags its burden over the ground, half flying and half walking, and other times the wasp seems to give up and just leave the bulk lying on the ground. Typically the carried thing is a stunned spider or caterpillar, but it can be other things, too. Organ-pipe Mud-daubers and Spider Wasps specialize in spiders. Potter wasps and Paper Wasps usually go with caterpillars, while Thread-waisted Wasps choose grasshoppers.

At this time of year many wasps are provisioning their nests with food supplies for their future offspring. Here is the average scenario:

A wasp stings its chosen prey, paralyzing it but not killing it. The wasp carries the victim to its nest, which may be a hole in the ground, a mud-dauber nest, a paper nest, or whatever. The victim is then placed in a cell of the nest along with the wasp's egg, and the cell is sealed. The victim continues to live in a paralyzed state, possibly for a long time, even until the following season. When the wasp's egg hatches, the larva consumes its paralyzed, still-alive food supply. The reason the prey is paralyzed and not killed is simple: If it were dead, it would decay. The wasp thus utilizes the prey's own immune system to keep it fresh for its eventual eating.

*****

BARN SWALLOWS & BEETHOVEN

One day this week I sat in my rocking chair in the barn door while the usual late-afternoon storm darkened the sky and growled. As I watched swallows cavorting over the Loblolly field, on the radio Beethoven's wonderful Eighth Symphony was playing.

The symphony's first movement is often dark with wrathful emotions, yet every now and then there are bursts among the bassoons and drums that have always struck me as very like laughter. The whole piece is on the one hand deadly serious, yet, throughout, there are unmistakable explosions of horse-laughing glee. It's very like swallows playing in a stormy summer sky.

History tells us that when Beethoven wrote the good-natured Eighth he was ill and profoundly disturbed by the political events and wars of his time. In the same vein, whenever I hear the Dalai Lama speak, he seems to laugh a lot, despite the plight of his people under Chinese domination. When I was in India I met several holy people and their faces always glowed with cheerfulness, despite the poverty and degradation in which they lived. In this world of collapsing ecosystems and ongoing mass extinctions of species, The Creator populates the darkening sky with playful swallows.

As the storm broke and the Loblolly field heaved beneath wind and rain, those swallows took their time getting to safety. And I could only look on dumbly and feel ashamed that in my own life maybe I have been too slow at catching most of the jokes around me, and too clumsy ever to dance.

*****

MISSISSIPPI KITES

On Tuesday afternoon while I worked at the computer I heard a big wind coming through the forest in advance of a storm. Here you can hear those winds long before they hit, sounding like a big waterfall. Quickly I turned off the computer to avoid voltage spikes from falling tree limbs hitting the wires, and stepped outside to enjoy the spectacle.

A Mississippi Kite, Ictinia misisippiensis, hovered directly above me facing into the wind and when the gusts began knocking him about and bending the biggest trees, he just drew in his wings, screamed louder, and I am sure that he was doing exactly as I was, just enjoying the storm. I must tell you my kite story.

Early this spring a pair of Mississippi Kites arrived from their wintering grounds in South America (as far south at Paraguay) and for several days hung around a big pecan tree not far from my trailer. Then one bird disappeared from the scene but, for a long time afterwards, the remaining bird had come and gone on a daily basis. During most of most days he or she could be spotted sailing in tight circles on thermals above our fields. When both birds disappeared, my impression was that the pair had nested in the big pecan, had produced at least one offspring that had been fledged, and somehow they had managed to pull the whole thing off without my being able to watch the details.

Before they'd gone, one dusk right as a violent storm was beginning to let up, while it still rained, the wind was gusty and lightening was striking nearby, I heard one of the kites calling with a very urgent tone in its voice. Then there was a different call, obviously also a kite, but higher pitched and sounding nervous. I rushed outside only to see the silhouettes of two kites merging with the forest's shadows. I think that this was the moment of nest-leaving for the young, and I am amazed that such an unlikely moment was chosen. Yet, if you're a kite wanting to hide your kid's nest-leaving, what better time?

What a secretive bird this kite is! How I admire its sharpness and wisdom!

Kites are hawk-like birds. All birds are divided into about 36 bird "orders." There's the "duck order," the "penguin order," and the "hawk-and-falcon order," for instance, with kites being members of the latter. That order is divided into 3 families. One family is the falcons, another the ospreys, and the third, the really big one, holds the hawks, eagles and kites.

Kites are especially graceful on the wing. They hover while hunting and when prey is spotted instead of diving headfirst they descend feet-first, seize their victim, then swoop skyward again. Mississippi Kites are fairly small, only 12.5 inches long, as opposed to, say, Turkey Vultures, which are exactly twice as long. Therefore kite food is small, mainly grasshoppers and dragonflies, plus a few mice, toads and small snakes.

*****

752 BATS (SOUTHEASTERN MYOTIS)

One reason I find myself at this precise spot in the forest is that there's an old cistern here. It's like a 20-foot-deep, 10-foot-wide Grecian urn buried in the ground, with its 4-foot-wide and 3-foot-high neck sticking above the ground's surface. I would not be surprised to learn that the cistern was placed here during slave days, to provide for a cluster of slave homes.

This cistern was supposed to provide me with water. I built my outside kitchen so that water from its tin roof would drain into the cistern. However, just days after I arrived and cleared the thicket of honeysuckle overgrowing the cistern's neck, both bats and Chimney Swifts moved into the cistern. They are still there. At first light each morning the bats flutter into the cistern after their night of feeding, then a while later Chimney Swifts streak out of it. Then at dusk the operation is reversed.

Of course this situation presented me with three choices: 1) drink water filled with bat and bird poop; 2) cover the cistern and keep the critters out, or: 3) turn the cistern over to the critters and get my water elsewhere.

Naturally I chose the last alternative, and I consider it an honor to share my space with these interesting and beautiful beings.

I've learned a good deal from the bats, which the books name Southeastern Myotis (sometimes Mississippi Myotis), and whose Latin name is Myotis austroriparius.

First of all, I've learned to not leave buckets next to the cistern, because twice I've found dead bats in the buckets' bottoms. Bats use a sophisticated form of echolocation -- bouncing high-frequency sounds off objects to figure out where things are -- and clearly to bat SONAR an empty bucket looks a lot like a cistern's entry hole.

I've also learned that bats can do mysterious things. Last fall I was sleeping outside beneath the mosquito net on my four-foot-high sleeping platform when I was awakened by a bat inside my net, fluttering back and forth the net's length. The bat must have pushed its way beneath the netting, which was draped onto the plywood surface heavily enough to keep all mosquitoes out. That night with a flashlight I was able to take a long look at my captive from six inches away as it hung on the inside of my netting. It's an amazing looking thing. Of course as soon as I lifted one side of the netting the bat nonchalantly flew out and immediately began darting among flying bugs.

I'm thinking about bats nowadays because for the last week each dawn I have seen more bats fluttering inside my outside kitchen than ever before. Their many wings cause a considerable whir in the morning air and though several may dart between my legs as I'm conducting my stretching exercises before jogging, they never touch my skin. They do often touch my beard, however, but that's because bat SONAR doesn't register a hermit's beard-hairs.

This Sunday Morning, the moment the first Cardinal sang and I couldn't even see that the western horizon was lighting up yet, I slipped from beneath the mosquito net and took a seat next to my cistern's neck, with my face about two feet away. It wasn't five minutes before the first bat entered. Ultimately I counted 752.

Two different forms were clearly present, a small, black one and a larger, paler one. However, I don't know whether this means that I have two different species, or whether there are just larger older ones and smaller young ones. I suspect that it's the latter. That's because several bats missed the basketball-size hole in the metal plate covering my cistern, and fluttered around on the cover for a second or two before regaining enough composure to dive through the hole, and all of the hole-missers were the small, black kind. According to a Web site, at this time of year juvenile Southeastern Myotises should be for the first time joining their elders on foraging expeditions, so those small black ones may be inexperienced young.

In nature there's a general rule that the more sophisticated an animal species is, the fewer offspring it produces. Couples of most Myotis species produce only one young per year, but Southeastern Myotises typically give birth to twins. I suppose this means that my bats are among the less sophisticated species in the large, smart family of Myotis bats. Still, the general low bat reproduction rate hints at the truth: That all bats are extremely complicated, highly evolved, marvelous beings. Also, that bats are very vulnerable to man's predations, because after any disaster affecting their numbers bats need a long time to recoup their numbers.

Yes, I am very proud of my 752 bat neighbors.

*****

ON THE CHARM OF PREDACEOUS DIVING BEETLES

I think most of us are wired to be "charmed" by certain things, at least when we're children and our minds are still open. The term "charmed" is too weak for the state of mind I'm describing, but I don't think English has any better word. I'm referring to a feeling akin to "love at first sight," except that it's a fixation on something besides another person. It amounts to an inexplicable, perfectly irrational, passionate fascination for something.

I've always thought that "being charmed" by something was the Creator's manner of nudging our lives toward certain paths leading to fulfillment. For example, as a child I was charmed by many things, especially trees and turtles, so here I am still talking about trees and turtles. One of my lesser charmings focused on Predaceous Diving Beetles.

On the farm in Kentucky we kept large, wooden barrels beneath the eaves of one of our sheds for collecting water for laundry and bathing. Predaceous Diving Beetles took up residence in the barrels and I spent hundreds if not thousands of hours with my head over the barrels' rims looking down at them. They were about 3/16-inch long, oval shaped and brownish with a black band at the rear end (the brownishness revealed itself as golden flecks in bright sunlight).

About all my beetles did was to paddle about within the barrels' water looking for tiny critters to eat, often coming to the water's surface to take air into their rear ends, thus spending a lot of time upside down at the water's surface. What transfixed me was the beetles' ability to explore at will their three-dimensional, sunlight-charged world, alternately spiraling like vultures in the air, then diving deeply through clear water charged with sunlight that exploded inside tiny, free-floating algal cells. The beetles were like spaceships wandering among stars. Their liberty and scintillating milieu contrasted exquisitely with the life of farm-kid me stuck in a very fat body anchored in an obscure corner of rural Kentucky.

I've been thinking about those days lately because the barn-eave bathtub here in which I soak for a moment during the hottest part of each day has a nice population of Predaceous Diving Beetles. If you change the tub's water, the beetles will be back the next day. Mainly they feed on flying ants that descend in the wrong place.

By "Predaceous Diving Beetle" I mean one of many species belonging to the Predaceous Diving Beetle Family, the Dytiscidae. There's actually a second species in my tub, a larger, black one who bites my skin as I soak, but I've never been "charmed" by that one.

*****

FIRE ANTS & WANDERING GLIDERS

Speaking of insects capturing my imagination, this week at the edge of a field I came upon a gathering of dragonflies -- between 50 and 70 medium-size (body length 1.9 inch), yellowish individuals all of the same species, forming a very animated, diffuse cloud about the size of a normal bedroom. The cloud's epicenter lay over a fire-ant mound from which hundreds of fire ants were emerging, about a third of them being winged. As the winged ants fluttered into the air they were snatched by the dragonflies. I doubt that a single fire ant survived its flight and for that I am grateful to the dragonflies.

For about 15 minutes I stood there trying to identify the dragonflies with the Dragonflies through Binoculars book Jerry Litton gave me, but the creatures simply flew so fast back and forth above the fire ant mound that I couldn't see the details needed. I concentrated so hard on the darting insects that I got motion sick and had to go sit down.

In about an hour I returned and this time a couple of dragonflies were resting on bluestem stems and now I could see that they were Wandering Gliders, Pantala flavescens. And what a surprise when I read that "It is the only dragonfly found around the world, breeding on every continent except Europe." The book also considers it "The world's most evolved dragonfly" because of its exceptional ability to travel long distances, including over oceans, where they may fly day and night for thousands of miles. The species is known to feed in swarms, just as I was seeing, but the more normal fare is small insects stirred up by large animals.

The part about this species that sets me daydreaming is the book's remark that the species "drifts with the wind as it feeds on aerial plankton until an air mass of different temperature produces the rain pools in which it breeds."

Imagine -- floating for days high in the air, feeding on plankton suspended there, so attuned to air pressure and humidity that you know when temporary pools are forming below you. And it's true that I found this swarm about an hour after a nice shower. These dragonflies seem to dance through the sky like my Predaceous Diving Beetles dance through clear water.

One of my favorite books is a German one, Die unendliche Geschichte, or "The Unending Story" by Michael Ende. In the book, the hero Atréju rides about the world on a Glücksdrache, a "lucky-dragon," which is "a creature of air and warmth, a creature of unbounded happiness, and despite its enormous size, as light as a summer cloud."

These Wandering Gliders sailing in clouds of wing-glisten, so sensitive to currents of air, and tending to visit Earth mainly at that magical moment right as the sun comes out after a summer rain, are the closest thing I've ever seen to a real Glücksdrache.

*****

HONEYBEE STING

After I jog each morning I hose myself off but I keep sweating as I prepare breakfast at my campfire, as indicated by the honeybees who settle on my back, arms and legs as I work. I just ignore them and try to avoid annoying them. But Wednesday one got between my legs and when I took a step she thought she was under attack and I got stung.

When a honeybee stings you the first thing you should do is to see if the stinger has come off, for, if it has, the poison sac will remain atop the stinger pumping poison into your skin long after the bee has gone. Remove the stinger as fast as possible.

A sad thing about the bee losing its stinger is that the bee then dies within a few hours. By stinging you, the bee is committing suicide. Therefore, from the bee's point of view, the question of whether the stinging must take place is a critical one. Stinging is not done lightly.

A lot of thinking has been done about how bees could have evolved so that individuals are programmed to give up their lives for the community's sake. To understand the answer you have to think in terms of the bee community's genetic heritage being carried by the queen, not the workers. In this light, we are almost struck with a sense of injustice when we see how expendable the workers' lives are. There's nothing democratic or even-handed here. The workers are created simply to work for the community, to sting when there's a need, and then to die.

Some serious thinkers have proposed that among such socialized insects as bees, the "individual" should be better thought of as the diffuse community of bees, not the single bees we see at our flowers. In this concept the queen is seen as like a gland secreting hormones and the workers are like corpuscles in the human circulatory system roaming about doing whatever the queen's hormones dictate. Is there really a rule in nature that a body has to be in one place -- that hormones must be transported in veins instead of on wings and six legs? We have examples of distinct species merging to form completely new life forms (fungi and algae merging to form lichens), so why can't the opposite be true, one thing manifesting itself as a community?

For me these insights are important because part of the bedrock of my belief system is that I regard human beings as being no more than highly specialized mammals. In believing this I'm not at all belittling humans, but rather regarding other animals as much more complex, self-aware and beautiful than most people admit. Therefore, if what's spiritually important in me is my "sense of identity," my "consciousness," or my "soul," then in the diffuse bee-individual to whom I with great pride claim biological relationship, just where is the "sense of identity," the "consciousness," or "the soul?"

Already it's known that in our own brains consciousness or sense-of-identity doesn't reside in any particular cell or group of cells, or nerve or organ. Even people who lose half their brain continue thinking and functioning as regular humans, perhaps showing only a certain "flatness" in their personalities. This thing we think of as our consciousness -- ourselves -- appears to just happen, maybe as a natural consequence of being embedded inside a lot of complex electrochemical circuitry. If that's the case with bees, then how pretty it is to think of the bee soul as being focused in the hive, but diffusing outwardly into communities of flowers in the fields.

Of course once you start thinking in this direction, then you come face to face with Gaia -- the Earth-Ecosystem-self-awareness-complex. In other words, maybe the Earth does feel, and react, like a single living organism. Certainly a lot of what happens in Nature appears to support that idea. For example, ecosystem-destroying humans on an overpopulated Earth are analogous to germs infecting a human body. As the human body reacts to disease by producing antibodies to control the germ population, Gaia's body does the same thing as diseases, famines and wars appear among us humans.

And, beyond Gaia, the Universal self-aware complex...

So, this was the train of thought blossoming from my bee-sting. How wonderful to be a thinking human animal.

*****

ROBBERS & CHEATERS

The high deer-fences around our organic gardens are beautiful now, heavily draped with the vine my kinfolk in Kentucky call Hummingbird Vine, and people around here often call Cypress Vine, since its leaves look like feathery green Baldcypress leaves. I planted these vines because they produce many, many scarlet blossoms which our Ruby-throated Hummingbirds and some moths and butterflies go crazy for. The vine is Ipomoea quamoclit.

Friday I was resting after doing some hoeing, just feasting my eyes on a big green and scarlet fence-wall with its circus of pugnacious hummingbirds and my eye was drawn to a Large Carpenter Bee (genus Xylocopa) visiting one red blossom after another. Thing is, this bee was not pollinating the flowers. It paid no attention to the blossoms' openings. Instead, it went to the outside base of each flower, thrust its "tongue" down between the corolla and the calyx, and robbed the flowers of their nectar.

"Rob" is the right word because flowers are designed so that their pollinators "pay" for the nectar they collect by pollinating the flowers -- bringing other flowers' male pollen to their female parts, then carrying the flower's own pollen to other flowers. But this bee was actually slitting each blossom's corolla so it could get at the nectar inside, completely bypassing the flower's sexual parts. I examined the corollas after the bee visited them and I could clearly see the slit. It was violent robbery pure and simple.

All this is worth thinking about. It shows that Mother Nature condones robbery, at least on occasion.

As I was biking back from the gardens musing on the philosophical implications of this, I saw a striking mantle of white blossoms produced by the vine called Virgin's Bower (Clematis virginiana) completely smothering the top of a small tree in the forest. Well, vines are rather sneaky, too, for they climb into the forest canopy without taking the trouble to build their own sturdy trunks, like any decent tree or bush would. Vines "cheat" by gaining their support from others, and then they may well spread atop their hosts and shade them out, as the one I saw was certainly doing.

For one to whom "Nature is Bible," a bit of thinking "outside the box" (the box of conventional human thought) must be done to see that in the end all this is exactly as it should be.