NESTERS

Nowadays the world is filled with earnest nesters, and if I were the nervous sort I might be getting peeved at the whole thing.

Each morning a Carolina Chickadee comes tugging at loose threads on an old backpack hanging from the ceiling of my outside kitchen. This year the Carolina Wrens want to nest in my biking helmet, also hanging there. The other day I was outside reading with my legs crossed, felt something on my naked toe, and there was a wren with a straw in his beak perched there, apparently oblivious to the fact that he was tickling me.

The worst are the Eastern Woodrats. Each night they cause a huge racket thumping around in my kitchen and below my trailer. Twice this week I've negligently left my new ever-sharp knife on the kitchen table and twice the following morning I've had to crawl beneath my trailer to retrieve it from a foot-high heap of glittery nest-junk a woodrat is building there.

Well, actually I find it encouraging that spring has come and that once again such a homey, generous instinct as nesting is part of it.

*****

GREEN TO MAKE THE HEAD SWIM

All around my little trailer too-close-together Sweetgum saplings flaunt their new leaves right at eye level. Their profound greenness when the sun shines through them makes the head swim. Above me, the big Pecan trees are just beginning to put on leaves, so by looking up one can see blue and gray, but throughout the normal day I feel like a fish in an algae-filled aquarium left in the sun. The fish analogy is fitting because I feel as if I'm breathing this greenness, swimming and dreaming in it, absorbing it and having it flow through my veins.

The other morning I was staring into this three-dimensional super-greenness while listening to the radio about the upcoming Shuttle lift-off, and about the project in store for it upon reaching the orbiting International Space Station. The juxtaposition of this green-staring and radio listening conjured a flash of insight, or maybe even a vision.

The Space Station is a gangling thing bristling with solar panels. Therefore, my fleeting, radio-listening "vision" was this: The Sweetgum saplings around me right now are doing exactly what NASA is doing with the orbiting Space Station. Both the Sweetgums and the Space Station are putting out their solar panels to capture energy needed to function and stay alive. For a split second I saw that both the Sweetgum saplings around me and NASA are confirming and celebrating a fundamental formula around which Life on Earth has crystallized. That formula is this:

the sun --> capture of sunlight energy --> that energy used to grow and evolve

*****

CLOGGED EAR

About once a year my left ear gets infected, and this week has been its time. This has seriously reduced my bird-spotting ability.

That's because most birders develop an uncanny talent for precisely locating the positions of singing birds with their ears before they begin looking with their eyes. I seldom notice this ability until it's gone. This week, with one ear closed down, I have been at a loss to say whether a bird was before me or behind me, to the right or left.

There's a benefit to this loss, however, assuming that the hearing returns as it always has. That is, I am reminded of what an amazing invention the human body is. I am obliged to reflect on all the things that can go wrong with a body to affect not only its hearing, vision and other senses, but also its sense of balance, blood-sugar level, the functioning of the heart and brain...

What an amazing fact that back in 1947 the button on my body-machine was pushed, and I've been going every since with very modest maintenance. In college I studied the chemical pathways involved in metabolism and respiration, how blood pH is buffered... It is all so complex, so majestically ingenious. Really it's amazing that we can ever feel good for a moment, yet I feel good nearly all the time. Every moment of feeling good is a tremendous gift.

*****

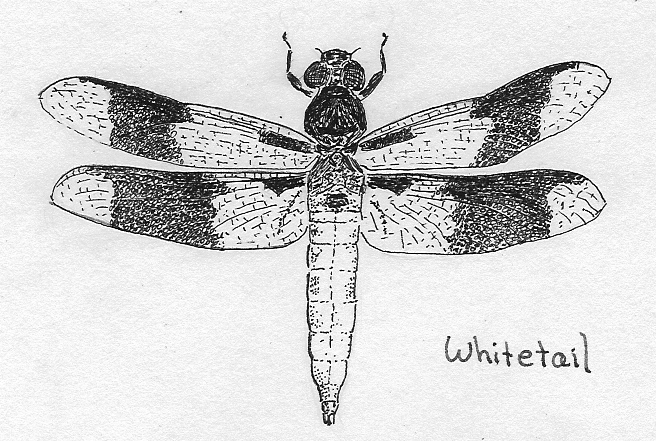

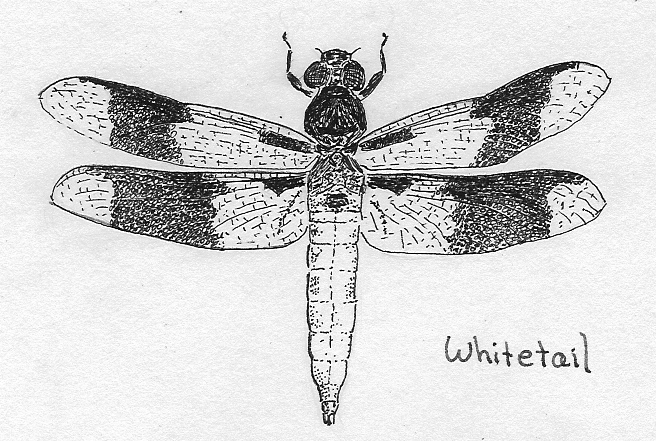

WHITETAILS, CORPORALS & PONDHAWKS

A while back wildlife photographer Jerry Litton from Pelahatchie gave me the Dragonflies through Binoculars fieldguide. This was a wonderful gift, for it opened a whole new world to me. Of course I've been watching dragonflies all my life and I thought I knew all about them, but when anyone begins studying anything seriously for the first time, it's quickly apparent just how little really was known.

This week I took the new fieldguide and my binoculars down to the pond and here are the three dragonfly species I identified with certainty after about an hour of watching:

Common Whitetail, Libellula lydia, a 1.7-inch long, black-and-white, chunky species abundant from coast-to-coast. When the air is chilly it faces the sun and raises its abdomen to increase its body temperature. Males compete with one another and the one who can fly vertical loops around his opponent wins.

Blue Corporal, Libellula deplanata, a 1.4-inch long, pale blue, thick-bodied species mostly of the US Southeast. At the base of each wing appear two narrow, brown streaks (corporal stripes). Males patrol along banks, often hovering.

Eastern Pondhawk, Erythemis simplicicollis, a 1.7- inch long dragonfly with a slender, blue abdomen that turns green at the thorax (chest area), and with a green head. The abdomen ends with two, tiny white points (cerci) -- a good fieldmark. Found in most of the eastern and central US, this is one of our most ferocious species, even attacking members of its own species. Sometimes it lets humans and other large animals flush its game. Males defend territories of about 5 square yards and enter into contests in which one flies under and up in front of the leader, then the new follower does the same to the new leader, and this maneuvering may continue up to a dozen times.

By the way, low-powered binoculars that can focus up close are far better for dragonfly watching than powerful ones.

******

THE WORLD OF DRAGONFLIES

Now that I'm sensitized to dragonflies, I look for them every day the way I do birds, and every day I discover new things about them. What an interesting, even surreal, world they live in!

Dragonflies, being a fairly primitive group of insects, undergo simple metamorphosis. Therefore they don't pass through a caterpillar and pupa stage like butterflies and moths. When a dragonfly egg hatches, a small edition of the adult emerges, known as a nymph. This nymph has the basic structure of the adult dragonfly, except that it is wingless, and aquatic -- it lives completely underwater.

Over 300 dragonfly species occur in North America, displaying endless variations in habitat preference, mating rituals and life cycles. Some of the strangest aspects of the dragonfly's life cycle relate to its parasites. Dragonfly eggs are parasitized by very tiny wasps that fly underwater to find the eggs. Other parasitic wasps have been seen riding on dragonflies waiting for eggs to be laid. A certain biting gnat sucks blood from dragonfly wing veins, even while the dragonfly is flying.

Other behavior to watch for is "basking" in sunlight on cold days, "wing-whirring" to warm the wings and keep them at peak efficiency, and "obelisking," or raising the abdomen high to collect less sunlight and keep the body cool. Some dragonflies allow breezes to lift their wings flaglike while others glide on their widened hindwings.

*****

NEATNESS AS ABOMINATION

A fellow in the vicinity has been busy this week bulldozing trees and bushes from a ditch running across his large, flat, grassy field. Someone remarked to me how wonderful it is that "things are getting cleaned up around here, really looking neat now."

Let it be known that when it comes to neatening up the landscape for neatness' sake, what I see is habitat destruction, and there's nothing neat about it. In fact, it's an abomination.

I use the word "abomination" advisedly. I am aware of the word's religious connotations, for many of us never see that term except in the Bible, where many things are classed as "abominations before the Lord." I use the word not in a religious context, but in a spiritual one, and in my opinion the destruction of life-giving habitat purely for the sake of appealing to the local community's concept of "neatness" is abomination before the spirit of the Creator.

For, when you look into the Universe and at the Web of Life on our little Earth, you see plainly that the Creator blossoms diversity out of nothingness, evolves sophistication out of awkwardness, and leaves strands of interdependency among all things. Whatever in spirit goes against this grand and beautiful theme of the Creator is "abomination."

The bushes and trees along that little ditch across the field provided a tiny island of habitat for a gorgeous diversity of living beings. A thriving local ecosystem of mutually dependent living things existed in an ocean of ecologically unstable monoculture grass. It was a polyphonic song sung in a desert.

And its destruction for the sake of neatening up the landscape is an abomination.

*****

BLACK VULTURE AND CONVERGENT EVOLUTION

Monday afternoon as I sat working at the computer suddenly there was a solid bang atop the trailer. I assumed a limb had fallen from the big Pecan tree above me. But then I heard claws scratching the aluminum top and all I could think of was the time a large iguana fell onto my tin roof in Belize.

My trailer is so small that I can stand in the open door and peep over the roof. I did that and came face to face with a Black Vulture with a wingspread of about 54 inches. Naturally he instantly exploded into a huff of whooshing wings, and vanished behind some trees. I suppose I was lucky to get by with whooshing wings, for vultures are known to indulge in projectile vomiting when upset.

Vultures are equipped with powerfully hooked beaks, beautifully designed to tear into flesh, just like a hawk's. However, unlike a hawk, a vulture's feet are weak. This introduces an interesting fact.

My old, tattered and moldy birding fieldguide, copyright 1966, places vultures along with hawks and falcons in a single order. In other words, the authors of that book in 1966 assumed that vultures, hawks and falcons were all very closely related, having shared a common ancestor not far back in evolutionary history. One problem with that idea was the vultures' famously weak feet.

Recent results from genetic sequencing show that our New World vultures are most closely related to storks and ibises, not hawks and falcons. Vultures in Europe and Asia continue to be placed with hawks and falcons, however, since their genes do indeed indicate a common recent ancestor with that group.

This is a beautiful example of convergent evolution. Millions of years ago there was an ecological niche open for birds to fill, that of eating carrion. Since the carrion-eating "job" is done most effectively by birds who look and behave in a certain way, eventually, as Old World hawky birds evolved to fill that niche and New World storky birds did the same thing, the two unrelated groups of carrion-eating birds -- American vultures and European vultures -- came to look and behave very similarly.

It's the same phenomenon that causes many Australian marsupial species to look like similar mammals here, though they are not at all closely related. Also it accounts for South Africa's succulent Euphorbias being so like our American cactuses.

*****

ON THE BEAUTY OF CONVERGENT EVOLUTION

Back to the vultures' convergent evolution. Again and again in nature you find very unrelated species evolving to look like one another. The reason is always the same: There's an optimum appearance and behavior for a species exploiting any specific ecological niche, so whatever ancestry you have, if you as a species decide to occupy that niche, your appearance and behavior will gradually evolve to the "optimum appearance and behavior" for that niche.

For me, the pretty part of this process is the confirmation that abstract ideals exist in nature and that, existing, they manifest themselves in the "real world." These abstract ideals are like ghosts suspended in eternity, beckoning parts of the changing world around them to come closer, to assume the character of the ideal's essence -- to become a material manifestation of the spiritual ideal.

Thus the Ghost of Carrion-eating Birds for millions of years beckoned toward the bird world, and out of the mists stepped Old-World members of the hawk order, and New-World members of the stork order. After millennia of walking toward the Ghost of Carrion-eating Birds, the Old-World hawk volunteers and our New-World stork volunteers now look almost the same.

What ghost beckons us humans forward as we evolve? What is the abstract ideal toward which we humans are walking out of the mists? What will be our final appearance and behavior?

For me, the search to an answer to those questions almost defines what it means to be a spiritual (not a religious) person. One's spiritual quest must be to glimpse the thing toward which humankind walks, and to keep consciously approaching that Holy Ghost, metamorphosing appropriately during the process.

My own journey is at an infantile stage, and I see the Ghost only at a very great distance and through profoundly disorienting mists. Yet already I can tell you three things I'm sure this Ghost favors.

1: She favors vitality over inertness.

2: She favors evolution over inaction.

3: She favors diversity over monotony.

These insights at first glance seem pretty general and unsexy. However, at this time when the flow of history is getting stuck in mindless conservatism, when fundamentalists deny the existence of biological evolution, and homogenizing "globalization" is the catchphrase of our times, maybe the human character just can't handle more than these elemental insights.

*****

CALLUSES

This week I've been grubbing Red Buckeye saplings from the hayfields and this has hardened the very slight calluses on my hands. I do just enough hoeing, scything and shoveling to keep respectable hints of calluses on my fingers and palms. These calluses got me remembering and thinking.

For two or three summers during the 1980s I was in Ulm, southern Germany, home to "Europe's tallest cathedral," begun in 1377. During my Ulm days, whenever I visited the cathedral, I went straight to an obscure little carving in an out-of-the-way corner portraying a naked man absolutely shaggy with long fur. Apparently back in 1377 he had been a famously pious hermit, someone who swore off clothing and other of man's conventions, and in reaction to Germany's habitually cold and rainy weather he had grown long hair all over his body.

So, the body can react to harshness in surprising ways. Corned feet once served our barefooted ancestors well. Long before humans had tools and worried much about clothing, maybe all humans looked like the shaggy hermit in Ulm's cathedral. For, the time since humankind emerged from the Stone Age is just a tiny flash at the end of many millennia of humans evolving in the context of small family or tribal units, on the open savannah and in the forest.

It's logical to think that today our inherited human genetic code continues producing humans meant to function in our ancestors' long-enduring world, not our recently acquired one.

Moreover, our minds, like our bodies, must react to stimuli and the lack of stimuli as if we were still in those distant times. But instead of protective calluses, corns, and shaggy hide, the mind must protect itself with mental armor. Much of my thinking this week has been about what that armor might be.

Today the mind reels before the complexity of the societies we humans have invented. Maybe the main "mental callus" protecting our fragile minds -- keeping us from going crazy -- is the ease with which we can withdraw into and identify with gross simplifications -- inflexible, black-and-white doctrines like racism, nationalism, communism, the trickle-down economic theory, and the world's many religions.

Grubbing up a Red Buckeye sapling in the middle of a sunny, windswept hayfield, I stare dumbly at the muddy, oversized root, and the sunburned, wrinkled hands holding the root. Crows call and I hear myself breathing. More than a little I sense the out-of-whackness of being what I am, being just here, doing this, the way I am in all this greenness and blueness and odor of crushed grass and earth-smell on the wind and the oily smell of my own skin in the sunlight, the cool wetness in my mouth, the feeling of fresh air rushing into my lungs... indulging in the illusion that Red Buckeyes need to be grubbed out...

And what can I do but just laugh and keep grubbing?

*****

MOMENTS OF PERFECTION

This week the world has been profoundly fresh and vibrant. Showers came and went leaving plants sparkling in spring sunlight, birds put on shows, new flowers blossomed every day, it was neither too hot nor too cold, and the mosquitoes weren't bad. The big Pecan trees above my trailer now sprout leaves and dense, dark clusters of catkins of male flowers. Bugs swarm among the catkins eating pollen, and worms attack the succulent new leaves, so birds rush from branch to branch eating bugs and caterpillars. On Saturday morning several Orchard Orioles and Baltimore Orioles, both bright-orange-and-black species freshly arrived from the tropics, along with some warblers and woodpeckers, made a gaudy circus above me.

Some afternoons white-topped thunderheads built up, and sometimes I just have to escape from the computer and go watch how the clouds' towering tops billow into the dark-blue sky. There's power and purpose in those enormous, rumbling, dark-bottomed clouds. Through my binoculars I see how cloud edges boil and seethe, and I stand imagining the howling, cold winds and mighty electrical charges at play inside the clouds, but when I take down the binoculars, the drama vanishes and all I see is pretty white against pretty blue, and perhaps later there will be a pleasant little shower.

Right before dusk there's a fresh spurt of activity among the birds and I walk along the woods' edge looking into the interiors of trees lighted by low-slanting sunlight. What a pleasure just seeing the colors of birds and butterflies in those theaters of glowing green leaves and black limbs gilded with orange sunlight.

If I had a million dollars I could never purchase the pleasure and contentment I have enjoyed for free during this past week.

*****

HONEYSUCKLE STAGGERS

Tuesday morning for the first time this year during my dawn jog I ran through a moist, warm pool of air suffused with the odor of Japanese Honeysuckle. My legs almost buckled as I was swept with a wave of mingled perfume-inspired nostalgia, memories of distant romances, and a need to be intimate and vulnerable... All very un-hermit sensations.

Well, it's been shown that much mammalian behavior (and therefore human) is linked to the effects of airborne chemicals known as pheromones -- especially pheromones produced by members of the opposite sex. Pheromones may or may not smell, but one thing they can do is to trigger hormone production, and you know how crazy you get when your hormones act up. Thing is, odor-molecules of flowers are often very similar in shape and size to pheromone molecules. In other words, I got the honeysuckle staggers because my body reacted to the molecules creating the honeysuckle aroma as if they were molecules of sex-associated pheromones.

There's been a good bit of research on how certain odors sexually arouse humans. Amazingly, among the most potent of odors is that of lavender combined with pumpkin pie. That fragrance causes a 40% increase in, as the researchers put it, "penile blood flow." The odors of orange, black licorice, cola and Lily-of-the-valley also cause significant excitement.

On a spiritual level, I find the effects of honeysuckle odor to be confirming with regard to my world view that all us living things, from fern to bee to human, are intimately interrelated, all of the same stuff, all dancing to the same Earth-tunes, and all vulnerable to the same Earth-abuses. I don't mind if a honeysuckle tricks my gonads. It's a good joke, a God-joke.

*****

A KETTLE OF HAWKS

Late Wednesday afternoon I noticed some hawks overhead and, as I watched, ever greater numbers of the same species began passing by. They were Broad-winged Hawks, and they were all sailing west-northwest, never beating a wing, just gliding in straight lines. Some were fairly low and others were very high. Sometimes they appeared alone, sometimes in small groups, and one cluster of about a dozen passed by.

"Cluster" isn't the right word, for this kind of hawk migration is so spectacular that there's a special word for it. I was witnessing the passage of a kettle of Broad-winged Hawks. Actually, my kettle of about 30 wasn't a particularly notable one. Above Duluth, Minnesota up to 10,000 Broad-winged Hawks have been spotted in one day. A more general name for any group of hawks is "cast."

It was typical that those Broad-wings glided above me without beating a wing. As Broad-winged Hawks migrate they locate rising air currents, or thermals, and circle inside them until they are high in the sky. Then they break away and glide in their chosen direction, not beating a wing if they can manage, until the next thermal.

This fairly common, forest-loving hawk spends winter from southern Mexico south to Peru and Brazil, and in southern Florida. During the spring the species migrates northward along the Gulf Coast. Entering the US they follow the Texas Gulf Coast as it curves around eastward to meet Louisiana. Finally they fan out throughout the forested part of eastern North America and if you look at a map you'll see why a lot of them pass right over us.

What a majestic passage this was. What a pleasure knowing that the Broad-winged Hawk sky-highway passes right above us at Natchez.

*****

GREEN, BLUE & BLACK

Especially at dusk you see it. The Mockingbird and maybe a Mourning Dove or a Cardinal forage in the grass, vividly tiny in all the panoramic greenness. Movie-projector sunlight flames in low from the west onto the earnest little birds earthworming amidst millions and millions of grassblades. On-pouring sunlight stings one's cheeks and squints the eyes, the birds' shadows are black, and each grassblade's slender sliver of shadow is black, else there's just green beneath the blue sky and the birds' black shadows stretch across the green grass and the birds themselves are hardly there at all, hopping silently, alert and something dangerous for earthworms, but nothing more substantial than that, specks in an enormity of blue, green and black.

Those pictures of Earth suspended in empty black space show a sphere that is green and blue, with white clouds and brown deserts. No deserts here, so out with brown. No clouds here, so out with white. It's the blackness in the formulation that leaves one thinking, the blackness that makes edges, is either all or nothing, depending on which side of green and blue you stand.

How pretty is a bird at dusk in green grass, sunlight from the deep blue sky slanting in from the west, the bird casting long black shadows. Nothing can be more alive than this.

*****

FOCUSING

With so many things in nature going on right now, my mind tends toward diffusion. For example, my thoughts are snared by the fluty song of the Orchard Oriole, and then come reflections on how this bird has just arrived from tropical America, and then I remember all the habitat destruction there and here, and then the question arises as to who will eat the bugs who eat the plants around me now, if not the Orchard Oriole, and what that will mean for these forests and fields... And there are dozens of such birdsongs and other things snaring the mind all the time, hundreds of meditations and questions associated with each, and thousands of potential scenarios.

Something tells me it's not good to let the mind think diffusely all the time, or even most of the time, so regularly I yank my mind out of that mode, and do focusing exercises.

For example, this morning with my binoculars I walked around focusing my lenses on individual things, just looking at them for a long time, as if I were standing before a piece of art on a museum wall, and I kept looking until I was satisfied that I had seen something important there.

I focused on a certain freshly emerged green oak leaf with sunlight rampaging through it. I don't believe there has ever been a design in all of Paris more expressive and perfect than the curl of that leaf just as it was during that particular moment of sunlit perfection. I focused on a feather with dew on it. I can't recall any painted picture in any museum anywhere evoking such pathos as that wrecked, wet feather. For long moments I beheld a yellow oxalis blossom all surrounded by green grass, and I saw -- really saw, saw as well as my mind could see at that time -- the grain in a weathered fence plank, and a cluster of pebbles in the sand at the creek's edge.

****

GRINNING COYOTE

Wednesday morning as I worked at the computer I glanced out my screen door and spotted a coyote working through the dense Sweetgum saplings beyond my kitchen. It was a young adult, full sized, stopping to sniff at this and that. He was so at ease that his face muscles let his lips sag into what seemed a self-assured grin. I wasn't surprised to see a coyote, for often I hear their calls and after every rain I see their prints.

At first I thought he was a neighbor's dog so I stepped outside to shoo him away, for these loose dogs terrify the deer and other wildlife here. But then I saw him more clearly and I was amazed that he hadn't heard my door as it scraped open, and never even looked in my direction where he could have plainly seen me and the camp. He passed within twenty feet of me and never noticed anything.

When I saw how oblivious the coyote was to my presence I felt a pang of regret. He was letting his guard down and if he keeps that up someone will shoot him. On the other hand, his mental laziness also made me feel as if he were some kind of brother to my own sometimes-lazy and sometimes-vulnerable self.

*****

DUSK FROM INSIDE A BLACK WILLOW

Several Black Willows about 15 feet tall grow around the Field Pond. Inside one multi-trunk tree I've placed a board so I can sit about half a foot above the water. From among the trunks I have a good view of the whole area and when I'm quiet wildlife doesn't seem to see me at all.

It's especially nice as the sun goes down. If it's been a warm day and the evening sky is clear, in the twilight at dusk the temperature drops very fast and curls of mist rise from the water's surface. Sometimes half the pond's face is animated with knee-high fog-curls all silently drifting in one direction. In a few minutes they all drift the other way. Meanwhile, it grows darker and darker.

It's a paradox of dusk that details of relative distance emerge as fog gathers. The distant line of trees grows pale because of mists rising over the field, while things closer, being seen through less mist, are darker and better defined. In full sunlight, things look flatter.

Then the deer come out with their huge ears twisting in all directions, their black noses and eyes the only hard points in the gauzy scene. As the deer graze nervously in open areas, all around me the pond scintillates with the shrill, measured clicking calls of Northern Cricket Frogs and the sound of continual, random splashing. The splashing is caused by fish and frogs jumping for mosquitolike insects laying eggs on the water's surface.

The mosquitolike insects try hard to avoid their predators, zigzagging and hovering about six inches above the water. Regularly they dip to the water's surface and with the tips of their abdomens lay eggs there, the whole egg-laying process taking only a fraction of a second. Yet this is time enough to attract a jumping fish or frog. Usually the insects escape, but sometimes they simply disappear from view in an instant too fleeting for my mind to register the details.

Then night sets in. I stand wondering how many snakes lie in the shadowy tangle of Japanese Honeysuckle I must wade through to get to my bike, and realize that I'm wet with cold fog. The delicious chill felt as I pick my way through the thicket comes from both the night air and from within.

*****

A PROFOUNDLY ENCOURAGING THOUGHT

The best moment of Friday's birdwalk came toward the end when for the first time during the walk I entered a broad open area. During the whole walk I'd not heard or seen either a Field Sparrow or a Prairie Warbler, but as soon as I was in the field both were heard within seconds of one another.

Anyone familiar with the calls of our birds knows that the songs of the two species are similar in that both calls ascend the musical scale while accelerating in tempo, like a dropped penny circling on a tabletop. Their main difference is that the warbler's call is buzzy, while the sparrow's is crystal clear.

So, of all the birdcalls I heard Friday, why did these two very unrelated species occupying the center of a large field possess such similar, ascending, ethereal calls? And why do these birds' calls approximate what I myself would compose if I were asked to create a short musical phrase conveying the feeling of being a small thing earthbound, looking into the open sky with its expressive clouds, light-charged blue spaces, and its profound openness?

On Friday as I walked across the big field the notion occurred to me that maybe the field had a message, and that the species known as Field Sparrows and Prairie Warblers were both evolving toward expressing it. Both species were in the process of reaching for the ultimate perfect timbre and phraseology for expressing the field's message, and already they had evolved to the point where their expressions were similar.

In fact, maybe every spot on Earth has a certain mood, or states a certain truth, and if you are a species evolving there, or if you're a human sensitive to what is going on there, what eventually, inevitably results is a glad, simple, songlike expression conveying that feeling or insight, passing it on to others.

Gloomy, shadowy forest brings forth haunting, fluty Wood Thrush calls. The break of dawn on foggy mornings erupts in good-natured Wild Turkey gobbling. The perspective of high perches watching over lower worlds is the Red-tailed Hawk's cry. Absolute freedom of movement inside the open sky itself is Chimney-Swift twitter, and the sound of being earthbound looking into the open sky -- that's the upward sweeping, tempo-increasing call discovered independently by both the Field Sparrow and Prairie Warbler, in an occasion of convergent spiritual evolution.

If such is the case, it can be important, for it suggests that when finally all our forests, fields and marshes are destroyed, if just one sprig of crabgrass remains on an eroded knoll, and there comes to this place just one child to behold what is there, think about it, love it, and hear what it has to say, then wisdom and hope can be reborn again as the child carries the grassblade's message forward.

*****

PRIMITIVE MAGNOLIAS

This week the Tulip Poplars' wonderful flowers got me thinking about the relationship, if any, between their special beauty and the fact that, according to the fossil record, analysis of floral structure, and gene sequencing, the Magnolia Family to which the Tulip Poplar belongs is one of the most "primitive" of flowering plants. There were magnolias during dinosaur times 130 million years ago.

Among the "primitive characters" exhibited by Magnolia Family members are their woodiness, their simple and alternate leaves, and their showy flowers with long floral axes, poorly developed styles and stigmas, leaf-like stamens, spiral arrangement of parts, and their pistils being separate from one another. ("Modern" families include the sycamores, walnuts, oaks and dogwoods.)

Is there a connection between the beauty of species in the Magnolia Family, and their primitiveness?

A few years ago a shrub called Amborella, found only on the island of New Caledonia in the South Pacific, suddenly became famous. Of all living flowering plants on Earth, it was revealed to be the most closely related to the very first flowering plants. Amborella is not in the Magnolia Family, nor are its flowers particularly large and showy. In habit it's a normal shrub.

So, the magnolias are primitive, but apparently their great beauty isn't closely tied to their primitiveness. I have no regrets about learning this, for the unspoken, unwelcome corollary of the "primitive = beautiful" equation is this: That inevitable evolution perpetually nudges us all toward what is more efficient, but gray; toward what is more productive, but mediocre, and; toward what is more promiscuous, but less vital.

Now that I think about, when I look into the skies at night, or ruminate on the matter of subatomic particles, I find no paradigms in those worlds to support the notion that "primitive = beautiful," and I have to wonder wherever I got that idea. On the other hand, the facts that great things can arise from plain beginnings, and that special beauty can appear anyplace unexpectedly, do fit paradigms glimpsed in the cosmos and in the mathematics of the inner world.

Before, the Magnolia Family's beauty was to me like the beauty of Gouguin's Tahiti paintings. Magnolias seemed to support the idea that being unsophisticated, rustic, elemental -- in and of itself -- was reason enough to explain their beauty. But now I see this: Guaguin's paintings are wonderful not because he captured the essence of primitive Polynesian folk, but because Guaguin was a great artist. Likewise, being primitive doesn't make Earthly things beautiful. What does is the craftsmanship of our Creator.

Step by step old prejudices and assumptions fall away, and new ideas and insights appear and evolve. This week it was the flowering Tulip Poplars who guided me.