What do you see at the right? Before you look hard, let me tell you that the flower-like thing behind the wasp is just a plastic decoration on a neighbor's bathroom wall.

Maybe when you study the picture you see a paper wasp guarding her nest, and if you're really sharp maybe you notice the little eggs at the bottom of each nest cell. Now, here's what you missed:

THINKING IN TERMS OF LIFE CYCLES

Let's think a little about the life cycle of the kind of wasp shown above.

Many species of paper wasp, genus Polistes exist, and the creation of paper nests varies from species to species. In some species only one wasp establishes a nest, while in others several may cooperate. What follows is a simplified, generalized sketch.

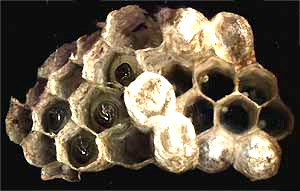

Let's say that it's early spring. A female paper wasp emerges from winter hibernation, builds a paper nest, and lays an egg in each cell. Inside the open cells, the eggs hatch into immobile, whitish, grub-like larvae. The mother feeds the larvae with chopped up pieces of prey she finds within flying distance of the nest. At the right you see a paper wasp carrying a "meatball" of stuck-together caterpillar flesh. Below, you see a nest with larvae on the left, and tiny eggs attached to their cells' walls on the right.

Since wasps undergo complete metamorphosis, the grub-like larvae metamorphose into pale, wingless, immobile pupae, which remain inside the cells. Since these pupae don't eat, the mother covers the cells. Sometimes these cell coverings are not enough to completely protect the pupae, however. Below, at the right, you see army ants in tropical Mexico carrying away a paper wasp pupa robbed from a nest. The ants will eat the defenseless pupa.

If all goes well, eventually the pupae metamorphose into adult female wasps. emerge from the nest cells, and at that point the mother wasp stops foraging, becomes a queen, and begins ruling her offspring, known as workers.

As summer progresses, the nest is enlarged, more eggs are laid and more workers are produced. Interactions among the queen or queens, and different-aged female workers are much studied, and relations vary tremendously from species to species. Often an individual's status depends on how successfully she dominates those around her. In some cases,a more aggressive and powerful wasp from outside the colony will come, overthrow the queen and become queen herself! Watching a wasp nest can be very interesting.

Here's the point of all this wasp-talk:

When you see something in Nature, it's like a door to open, a door to knowing even more interesting stuff than what's there in front of you. And the key to opening that door is to learn about that thing's life cycle.

Moreover, this insight applies not only to insects and other living things, but also to everything else in the Universe. In a sense, even rocks, clouds, ecosystems and stars have their life-cycle processes. Knowing where things came from, and the meaning of what you're seeing that thing doing right now, and being able to visualize how it all might turn out them, is all part of the magical process of seeing what's right before you. For the backyard naturalist, there's no more powerful thinking tool than to think in terms of life cycles!

LIFE CYCLES IN FIELD GUIDES

Nearly all good field guides are organized so that closely related organisms are considered together -- all wasps in these pages, all bees in those pages, etc. Moreover, each section of such field guides usually provides basic facts about the life cycles of the organisms being considered.

Here's an example. I go to my A Field Guide to Insects : America North of Mexico and read about members of the order Hymenoptera, superfamily Apoidea, family Apidae, subfamily Apinae, tribe Bombini -- in other words, the Bumble Bees. I read that most Bumble Bees nest in or on the ground, often in deserted mouse nests. Generally, Bumble Bee colonies die when winter comes, with just the queens overwintering and starting new colonies in the spring.

One reasonBeyond that, knowing that all bees are members of the order Hymenoptera, I automatically also know that Bumble Bees produce eggs that hatch into larvae, which develop into pupae, which metamorphose into adults -- because all members of the Hymenoptera undergo complete metamorphosis. Knowing that Bumble Bees are members of the family Apidae, automatically I have access to the knowledge that Bumble Bees possess long, slender glossa (tongues) useful for getting to nectar in the bottoms of flowers -- because all members of the Apidae have long, slender glossa...

THINKING EVOLUTION-WISE

Our understandings of life cycle features held in common with groups of living things -- such as all wasps and bees undergoing complete, not simple, metamorphosis -- can be much enhanced by taking into account the groups' evolutionary history. Consider the chart shown below:

Notice that at each fork in this evolutionary tree, there's a "primitive state" and something new arising from that primitive state.

At the chart's top we see that an early important innovation to evolve in the insect world was that of acquiring wings.  Today's wingless silverfish and springtail orders -- a silverfish shown at the right -- are said to retain the "primitive wingless condition." Primitive, wingless insects are thought to have arisen about 480 million years ago. Winged insects didn't come along until around 406 million years ago.

Today's wingless silverfish and springtail orders -- a silverfish shown at the right -- are said to retain the "primitive wingless condition." Primitive, wingless insects are thought to have arisen about 480 million years ago. Winged insects didn't come along until around 406 million years ago.

The first winged insects, such as dragonflies, held their wings at right angles to their bodies. From them arose insects who could fold their wings over their body when not in use. Then among insects with hinged wings, there arose new kinds of insects undergoing complete metamorphosis. Today we think of these more recently arisen forms as "higher" insect groups -- such as the butterflies, beetles, flies and bees.

The majestic evolutionary impulse flowing through Nature always is spawning new concepts enabling living things to better adapt to their environments. Seeing this not only helps us appreciate the relative sophistication of a butterfly or beetle, but also to admire and better understand the primitive forms. For, silverfish and springtails with their primitive winglessness and simple metamorphosis still are abundant in today's world, though most primitive insect forms have gone extinct. From the very beginning, the silverfish and springtails got some things right by being just the way they were.

The majestic evolutionary impulse flowing through Nature always is spawning new concepts enabling living things to better adapt to their environments. Seeing this not only helps us appreciate the relative sophistication of a butterfly or beetle, but also to admire and better understand the primitive forms. For, silverfish and springtails with their primitive winglessness and simple metamorphosis still are abundant in today's world, though most primitive insect forms have gone extinct. From the very beginning, the silverfish and springtails got some things right by being just the way they were.

And that's something to think about.